Aristotle’s Masterpiece, not a masterpiece nor by Aristotle, was a manual of advice on sex, childbirth and infant care first published in 1684. Its anonymous author took the name of the famous ancient Greek philosopher to give his material an air of intellectual and scientific authority. Aristotle’s Problems, a book about health and sex in question-and-answer format published in 1595, had established the philosopher’s reputation for expertise on sexual matters even though again the author had only borrowed Aristotle’s name. By the early 17th century, the name “Aristotle” was popularly associated with sexual knowledge. The Masterpiece sought to piggyback off of that reputation. In truth it actually contradicted Aristotle’s theory of conception, proposing a two-seed mechanism whereby a man and woman each contribute generative material to create new life while the real-life Aristotle believed there was only one seed, the man’s, which planted a baby in the lady’s womb field.

Aristotle’s Masterpiece, not a masterpiece nor by Aristotle, was a manual of advice on sex, childbirth and infant care first published in 1684. Its anonymous author took the name of the famous ancient Greek philosopher to give his material an air of intellectual and scientific authority. Aristotle’s Problems, a book about health and sex in question-and-answer format published in 1595, had established the philosopher’s reputation for expertise on sexual matters even though again the author had only borrowed Aristotle’s name. By the early 17th century, the name “Aristotle” was popularly associated with sexual knowledge. The Masterpiece sought to piggyback off of that reputation. In truth it actually contradicted Aristotle’s theory of conception, proposing a two-seed mechanism whereby a man and woman each contribute generative material to create new life while the real-life Aristotle believed there was only one seed, the man’s, which planted a baby in the lady’s womb field.

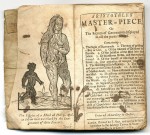

The book is a compilation of the most sensationalized parts of two 16th century volumes, The Secret Miracles of Nature (1564) by Levinus Lemnius and De conceptu et generatione hominis (1554), a midwifery manual by Jakob Rüff. It was one of almost two dozen books about midwifery printed in the wake of the great success of Nicholas Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives, published in 1651. What made the Masterpiece stand out in the crowd was its promise of advice on “the act of copulation” on the very title page. The more conventional midwifery texts were not so direct. In keeping with the finest tradition of sex sells, Aristotle’s Masterpiece became a bestseller for centuries, reissued in two more versions with additional material from later books and going through hundreds of printings in Britain and the United States. The 1728 version went through more printings than all the other books on midwifery combined and was still in print well into the 20th century.

The book is a compilation of the most sensationalized parts of two 16th century volumes, The Secret Miracles of Nature (1564) by Levinus Lemnius and De conceptu et generatione hominis (1554), a midwifery manual by Jakob Rüff. It was one of almost two dozen books about midwifery printed in the wake of the great success of Nicholas Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives, published in 1651. What made the Masterpiece stand out in the crowd was its promise of advice on “the act of copulation” on the very title page. The more conventional midwifery texts were not so direct. In keeping with the finest tradition of sex sells, Aristotle’s Masterpiece became a bestseller for centuries, reissued in two more versions with additional material from later books and going through hundreds of printings in Britain and the United States. The 1728 version went through more printings than all the other books on midwifery combined and was still in print well into the 20th century.

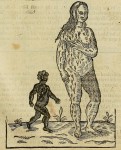

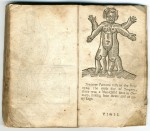

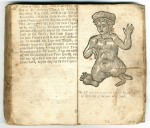

The inclusion of woodcuts yoinked from French barber surgeon Ambroise Paré’s 1573 treatise Of Monsters and Prodigies first published in English in an edition of his Works in 1634, played a part in the book’s success. Again the title page made it clear what readers could expect to find within: woodcuts of naked ladies and “monsters,” babies born with various anomalies. The title page woodcut was of a hairy woman and a black child, both the result of their mothers having seen something that imprinted on their fetuses during pregnancy or the moment of conception. The hairy lady’s mother while pregnant with her had beheld an image of John the Baptist wearing animal skins. The picture was imprinted in her mind on her developing fetus, resulting in the monstrous birth of a hirsute baby girl. The black child was, ostensibly, the son of two white parents who had a picture of a black man hanging in their bedroom. The mother happened to glance at it while having sex with her husband, and the result of that copulation was a black baby.

The inclusion of woodcuts yoinked from French barber surgeon Ambroise Paré’s 1573 treatise Of Monsters and Prodigies first published in English in an edition of his Works in 1634, played a part in the book’s success. Again the title page made it clear what readers could expect to find within: woodcuts of naked ladies and “monsters,” babies born with various anomalies. The title page woodcut was of a hairy woman and a black child, both the result of their mothers having seen something that imprinted on their fetuses during pregnancy or the moment of conception. The hairy lady’s mother while pregnant with her had beheld an image of John the Baptist wearing animal skins. The picture was imprinted in her mind on her developing fetus, resulting in the monstrous birth of a hirsute baby girl. The black child was, ostensibly, the son of two white parents who had a picture of a black man hanging in their bedroom. The mother happened to glance at it while having sex with her husband, and the result of that copulation was a black baby.

It was a tricky thing, this conceiving of a healthy, non-monstrous child. Allowances had to made for women’s colder humours, allowances which fortuitously required husbands actually take the time to excite their wives before getting to the business of insemination. Here’s some advice on foreplay justified by old-timey nonsense science.

It was a tricky thing, this conceiving of a healthy, non-monstrous child. Allowances had to made for women’s colder humours, allowances which fortuitously required husbands actually take the time to excite their wives before getting to the business of insemination. Here’s some advice on foreplay justified by old-timey nonsense science.

When the husband cometh into his wives chamber, he must entertain her with all kind of dalliance, wanton behaviour, and allurements to venery: but if he perceive her to be slow and more cold, he must cherish, embrace, and tickle her, and shall not abruptly, the nerves being suddenly distended, break into the field of nature, but rather shall creep in by little and little, intermixing more wanton kisses with wanton words and speeches, handling her secret parts and dugs, that she may take fire and be in flames to venery, for so at length the womb will strive and wax fervent with a desire of casting forth its own seed, and receiving the mans seed to be mixed together therewith.

But if all these things will not suffice to inflame the woman, for women for the most part are more slow and slack into the expulsion or yielding forth of their seed, it shall be necessary first to foment her secret parts with the decoction of hot herbs made with muscadine, or boyled in any other good wine, and to put a little musk or civit into the neck or mouth of the womb, and when she shall perceive the flux of her seed to approach, by reason of the tickling pleasure, she must advertise her husband thereof, that at the very instant, time, or moment, he may also yield forth his seed, that by the concourse or meeting of the seeds, conception may be made, and so at length the child formed and born.

The first edition of Aristotle’s Masterpiece was published by John How and, as printed on the title page, was “to be sold next door to the Anchor Tavern in Sweethings-Rents in Cornhil.” How registered it with the Stationers Company, an early version of copyright protection which allowed registrees to block publication of their works by unlicensed publishers, but he was unable to prevent pirated copies from getting out there almost immediately. Printers both anonymous and named cranked out copies starting within the first year of its initial publication.

The first edition of Aristotle’s Masterpiece was published by John How and, as printed on the title page, was “to be sold next door to the Anchor Tavern in Sweethings-Rents in Cornhil.” How registered it with the Stationers Company, an early version of copyright protection which allowed registrees to block publication of their works by unlicensed publishers, but he was unable to prevent pirated copies from getting out there almost immediately. Printers both anonymous and named cranked out copies starting within the first year of its initial publication.

Because it was considered a dirty book with all the sex talk and the naked hairy ladies and four-armed children, it wasn’t overtly sold by booksellers although most of them surreptitiously kept copies under the counter for the client in the know. It was sold by traveling peddlers, in general stores and, as stated in the first printing, in or next to taverns. Never officially banned, publication and sale of the book should in theory have been stymied by Britain’s Obscene Publications Act of 1857 and the 1873 Comstock Law which prevented its sale through the mail in the United States. By then it had such a long record of under-the-table printing and sale that it’s unlikely these hard to police laws had much of an effect on the book’s distribution.

Because it was considered a dirty book with all the sex talk and the naked hairy ladies and four-armed children, it wasn’t overtly sold by booksellers although most of them surreptitiously kept copies under the counter for the client in the know. It was sold by traveling peddlers, in general stores and, as stated in the first printing, in or next to taverns. Never officially banned, publication and sale of the book should in theory have been stymied by Britain’s Obscene Publications Act of 1857 and the 1873 Comstock Law which prevented its sale through the mail in the United States. By then it had such a long record of under-the-table printing and sale that it’s unlikely these hard to police laws had much of an effect on the book’s distribution.

Despite its wide popularity over the course of centuries, Aristotle’s Masterpiece is a rare book today. Out of more than 250 known editions published, very few intact copies have survived. Printed on cheap paper and thumbed through with much vigor, they were prone to heavy wear and having pages torn out. There are less than a dozen of the first edition known to survive, and most of them are incomplete. Two complete copies have recently appeared at auction. One of them sold at Bonhams in 2014 for $32,743, the other sold at Bonhams in 2015 for $29,105.

Despite its wide popularity over the course of centuries, Aristotle’s Masterpiece is a rare book today. Out of more than 250 known editions published, very few intact copies have survived. Printed on cheap paper and thumbed through with much vigor, they were prone to heavy wear and having pages torn out. There are less than a dozen of the first edition known to survive, and most of them are incomplete. Two complete copies have recently appeared at auction. One of them sold at Bonhams in 2014 for $32,743, the other sold at Bonhams in 2015 for $29,105.

Now a third complete copy has come on the market. It will be sold at Dominic Winter Auctioneers on March 2nd. The pre-sale estimate is £10,000-15,000 ($14,500-22,000). My favorite part is that the cover of this copy was made from a recycled land deed.

Now a third complete copy has come on the market. It will be sold at Dominic Winter Auctioneers on March 2nd. The pre-sale estimate is £10,000-15,000 ($14,500-22,000). My favorite part is that the cover of this copy was made from a recycled land deed.

The incomplete deed used for the covers in this copy appears, from the partially visible text, to be a title deed from 30 January [1686], and relates to property owned by George Speke [1623-1689, English politician. Speke was a Royalist during the English Civil War, but after the Restoration became MP for Somerset and an early Whig supporter in Parliament.]

I like to think George Speke donated his old paperwork to the cause of naughty book printing.

Roman police have discovered tons of refuse, everything from household trash to industrial waste, illegally dumped in the 2nd and 3rd century A.D. catacombs of Tor Fiscale, an archaeological park in east Rome. Situated on the Via Latina near the junction with the ancient Appian Way, the Tor Fiscale park is part of the vast Appian Way Regional Park. The small park is dense with archaeological riches. It is at the crossroads of six Roman and one Renaissance aqueduct whose arched galleries dominate the landscape alongside the 13th century tower that gives the park its name. It is replete with remains of ancient luxury villas, homes, tombs and underground caves dug out of soft volcanic tufa. Initially carved to quarry the stone, the caves were used by early Christians for gatherings and burials during the imperial era when the religion was viewed with suspicion and its adherents sometimes persecuted.

Roman police have discovered tons of refuse, everything from household trash to industrial waste, illegally dumped in the 2nd and 3rd century A.D. catacombs of Tor Fiscale, an archaeological park in east Rome. Situated on the Via Latina near the junction with the ancient Appian Way, the Tor Fiscale park is part of the vast Appian Way Regional Park. The small park is dense with archaeological riches. It is at the crossroads of six Roman and one Renaissance aqueduct whose arched galleries dominate the landscape alongside the 13th century tower that gives the park its name. It is replete with remains of ancient luxury villas, homes, tombs and underground caves dug out of soft volcanic tufa. Initially carved to quarry the stone, the caves were used by early Christians for gatherings and burials during the imperial era when the religion was viewed with suspicion and its adherents sometimes persecuted. Authorities came to suspect something was rotten underground during an investigation of illegal car scrapyards and waste disposal rackets in the area. On January 26th, about 20 people — police officers, personnel from Italy’s Regional Environmental Protection Agency (ARPA), municipal workers and members of the archaeological speleology organization Sotterranei di Roma (Undergrounds of Rome) — worked together to explore miles of the underground tunnels. They found a shocking amount of waste, including old refrigerators, mattresses, electronics, tires, batteries, hundreds of bags of organic materials full of various molds that may have been used in the cultivation of mushrooms.

Authorities came to suspect something was rotten underground during an investigation of illegal car scrapyards and waste disposal rackets in the area. On January 26th, about 20 people — police officers, personnel from Italy’s Regional Environmental Protection Agency (ARPA), municipal workers and members of the archaeological speleology organization Sotterranei di Roma (Undergrounds of Rome) — worked together to explore miles of the underground tunnels. They found a shocking amount of waste, including old refrigerators, mattresses, electronics, tires, batteries, hundreds of bags of organic materials full of various molds that may have been used in the cultivation of mushrooms.  In one of the deepest tunnels, they found a veritable lake of greasy black goo that is likely used motor oil. On the surface alone this lake of hydrocarbon pollution covers about 200 square meters (2,150 square feet), and preliminary analysis found the lake is more than a foot deep, so the total volume of toxic filth in this one spot alone is something in the neighborhood of 800 cubic meters (28,250 cubic feet). At some points the vaults of the tunnel appear to be impregnated with the goop, suggesting it was dumped from above rather than transported deep into the caves. The team took samples of the fluid to identify it and they will examine the surface to locate the entry point. There will also be extensive testing to assess whether the oil has seeped into the water table.

In one of the deepest tunnels, they found a veritable lake of greasy black goo that is likely used motor oil. On the surface alone this lake of hydrocarbon pollution covers about 200 square meters (2,150 square feet), and preliminary analysis found the lake is more than a foot deep, so the total volume of toxic filth in this one spot alone is something in the neighborhood of 800 cubic meters (28,250 cubic feet). At some points the vaults of the tunnel appear to be impregnated with the goop, suggesting it was dumped from above rather than transported deep into the caves. The team took samples of the fluid to identify it and they will examine the surface to locate the entry point. There will also be extensive testing to assess whether the oil has seeped into the water table.After making the shocking discovery, police used drones to fully explore the network of bat-and-mice-infested tunnels to try to establish the extent of the dumping.