The Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Museums contains the largest cycle of cartographic paintings ever created. The gallery on the west side of the Belvedere Courtyard connects the Sistine Chapel to the Tower of the Winds and is 120 meters (394 feet) long, longer than a football field and 20 feet wide. Its barrel-vaulted ceiling soars three storeys above the floor. The walls are covered practically floor to ceiling with frescoed maps of all the regions of Italy.

The Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Museums contains the largest cycle of cartographic paintings ever created. The gallery on the west side of the Belvedere Courtyard connects the Sistine Chapel to the Tower of the Winds and is 120 meters (394 feet) long, longer than a football field and 20 feet wide. Its barrel-vaulted ceiling soars three storeys above the floor. The walls are covered practically floor to ceiling with frescoed maps of all the regions of Italy.

The Gallery of the Maps was commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII so that he could travel the length of Italy without having to leave the apostolic palace. Dominican friar, mathematician and cartographer Ignazio Danti was placed in charge of the project. (Danti was also on the committee that reformed the Julian calendar, correcting its ancient miscalculations by cutting out 11 days so October 4th, 1582, was followed by October 15th, 1582, after which the new Gregorian calendar, named after the Pope, kept up with astronomical time.) During the course of 18 months from 1580 to 1581, Danti and his team — Flemish artists Matthjis and Paul Bril and Italian Mannerists Gerolamo Muziano and Cesare Nebbia, Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese and Ignazio’s brother Antonio Danti — painted 40 large-scale map frescoes of every region in Italy (plus Avignon, on account of it was owned by Popes for four centuries from the Babylonian Captivity until the French Revolution).

The Gallery of the Maps was commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII so that he could travel the length of Italy without having to leave the apostolic palace. Dominican friar, mathematician and cartographer Ignazio Danti was placed in charge of the project. (Danti was also on the committee that reformed the Julian calendar, correcting its ancient miscalculations by cutting out 11 days so October 4th, 1582, was followed by October 15th, 1582, after which the new Gregorian calendar, named after the Pope, kept up with astronomical time.) During the course of 18 months from 1580 to 1581, Danti and his team — Flemish artists Matthjis and Paul Bril and Italian Mannerists Gerolamo Muziano and Cesare Nebbia, Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese and Ignazio’s brother Antonio Danti — painted 40 large-scale map frescoes of every region in Italy (plus Avignon, on account of it was owned by Popes for four centuries from the Babylonian Captivity until the French Revolution).

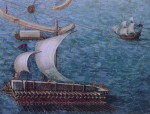

The maps are extraordinarily detailed and accurate renderings of Italy in the late 16th century. Following Danti’s meticulous cartographic cartoons, the painters stuck to what they knew was there. If there was something they weren’t sure about, they left it out. While they included traditional decorative figures like putti, sea monsters and Neptune and conflated historical elements like Roman ships with contemporary ones, the maps themselves. The topographical precision and perspective are extraordinary, lending these maps an almost 3D-like realism. Valleys, hills, lakes, even individual streets are all recognizable. Moving from southern Italy to the north, the east side of the room was painted with maps of regions that face the Adriatic Sea and the Alps; the west side featured regions facing the Tyrrhenian. Danti said that walking this corridor was like walking up Italy on the spine of the Apennines.

The maps are extraordinarily detailed and accurate renderings of Italy in the late 16th century. Following Danti’s meticulous cartographic cartoons, the painters stuck to what they knew was there. If there was something they weren’t sure about, they left it out. While they included traditional decorative figures like putti, sea monsters and Neptune and conflated historical elements like Roman ships with contemporary ones, the maps themselves. The topographical precision and perspective are extraordinary, lending these maps an almost 3D-like realism. Valleys, hills, lakes, even individual streets are all recognizable. Moving from southern Italy to the north, the east side of the room was painted with maps of regions that face the Adriatic Sea and the Alps; the west side featured regions facing the Tyrrhenian. Danti said that walking this corridor was like walking up Italy on the spine of the Apennines.

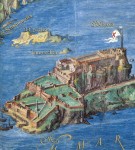

Every regional map is accompanied by a smaller view of its most populous city. Where you exit the gallery today are maps of Italy’s four major ports — Genoa, Venice, Ancona and Civitavecchia — and two views of the entire peninsula — ancient Italy and new Italy. At today’s entrance are maps of the minor islands and two momentous battles that were still fresh news when they were painted: the Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565 and the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, both won by the Holy League.

Every regional map is accompanied by a smaller view of its most populous city. Where you exit the gallery today are maps of Italy’s four major ports — Genoa, Venice, Ancona and Civitavecchia — and two views of the entire peninsula — ancient Italy and new Italy. At today’s entrance are maps of the minor islands and two momentous battles that were still fresh news when they were painted: the Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565 and the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, both won by the Holy League.

The ceiling vaults are painted with the patron saints of the various regions (Saint Ambrose for Milan, Saint Mark for Venice) and with important/miraculous scenes from Italian history (Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon, Hannibal and his elephants, the baptism of Constantine, Pope Leo I persuading Attila the Hun to withdraw from Italy, Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa meeting with Pope Alexander III, etc.) each covering the space above the maps of the locations where the events took place.

The ceiling vaults are painted with the patron saints of the various regions (Saint Ambrose for Milan, Saint Mark for Venice) and with important/miraculous scenes from Italian history (Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon, Hannibal and his elephants, the baptism of Constantine, Pope Leo I persuading Attila the Hun to withdraw from Italy, Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa meeting with Pope Alexander III, etc.) each covering the space above the maps of the locations where the events took place.

The next Pope to put his hands on the maps was not so keen on accuracy. Pope Urban VIII ordered a “restoration” in 1630 that just painted over details that had gotten blurred over the 50 years since their creation. A fresco depicting the Brenner Pass between Italy and Austria was painted over just because it was so high up on the wall it was inconvenient to repair. Born Maffeo Barberini, Pope Urban also had his family’s symbol, the bee, added to the maps wherever possible, if not advisable. (It was Urban VIII who stripped the bronze off the roof of the Pantheon to make cannon and Bernini’s baldachin in St. Peter’s Basilica, giving rise to the satiric pasquinade “Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini,” meaning “What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did.”)

The next Pope to put his hands on the maps was not so keen on accuracy. Pope Urban VIII ordered a “restoration” in 1630 that just painted over details that had gotten blurred over the 50 years since their creation. A fresco depicting the Brenner Pass between Italy and Austria was painted over just because it was so high up on the wall it was inconvenient to repair. Born Maffeo Barberini, Pope Urban also had his family’s symbol, the bee, added to the maps wherever possible, if not advisable. (It was Urban VIII who stripped the bronze off the roof of the Pantheon to make cannon and Bernini’s baldachin in St. Peter’s Basilica, giving rise to the satiric pasquinade “Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini,” meaning “What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did.”)

Six million people a year walk down this hall, bringing dirt, moisture and the vibrations from hundreds of millions of footballs with them that caused the plaster to lift from the walls and covered the brilliance of the original paint under layers of dust. Between that and the unfortunate past restorations, the frescoes were in dire need of attention. In 2011, the Vatican reached out to the Patrons of the Arts in the Vatican Museums, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of the Vatican Museums’ cultural patrimony, for help in funding a new restoration of the paintings that would rescue the plaster from impending doom and return works to their former splendour.

Six million people a year walk down this hall, bringing dirt, moisture and the vibrations from hundreds of millions of footballs with them that caused the plaster to lift from the walls and covered the brilliance of the original paint under layers of dust. Between that and the unfortunate past restorations, the frescoes were in dire need of attention. In 2011, the Vatican reached out to the Patrons of the Arts in the Vatican Museums, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of the Vatican Museums’ cultural patrimony, for help in funding a new restoration of the paintings that would rescue the plaster from impending doom and return works to their former splendour.

The restoration was sponsored by the California chapter of the Patrons. Half of the $2.4 million budget was donated by one Patron; the rest was raised through a map adoption program, with each Patron adopting an individual map and funding its restoration at either the $35,000 or $70,000 level. Because the maps are so extensive and so detailed, some patrons had the unique opportunity to adopt a map that with a connection to their family histories, for example the Castignano family adopted the map of Sicily because it included the hometown of their immigrant forebears, a tiny hamlet that barely registers on other atlases, while the Stanislawskis adopted the map of Umbria because of a family history of devotion to St. Francis of Assisi.

The restoration was sponsored by the California chapter of the Patrons. Half of the $2.4 million budget was donated by one Patron; the rest was raised through a map adoption program, with each Patron adopting an individual map and funding its restoration at either the $35,000 or $70,000 level. Because the maps are so extensive and so detailed, some patrons had the unique opportunity to adopt a map that with a connection to their family histories, for example the Castignano family adopted the map of Sicily because it included the hometown of their immigrant forebears, a tiny hamlet that barely registers on other atlases, while the Stanislawskis adopted the map of Umbria because of a family history of devotion to St. Francis of Assisi.

Art restorer Francesco Prantera and his team of experts began work in September of 2012. They anchored the plaster to the wall with an organic glue, and then set to treating the frescoes. They divided each map into 64 sections, the same sections the original artists used to paint them in the 16th century. Each of the sections was covered with special tissue-thin paper to absorb the old yellowed glue from a 19th century restoration. When the paper was peeled off, the newly vibrant color was protected with an adhesive made from a Japanese red algae called funori. Because the product is so expensive (one gram will run you 100 euros), the diagnostic laboratory of the Vatican Museums made their own extract directly from the imported seaweed. The restoration team then cautiously filled in areas of paint loss, reproducing the original materials used by the artists. The stucco was made from an ancient Roman recipe. The paints were all natural and free of chemicals.

Art restorer Francesco Prantera and his team of experts began work in September of 2012. They anchored the plaster to the wall with an organic glue, and then set to treating the frescoes. They divided each map into 64 sections, the same sections the original artists used to paint them in the 16th century. Each of the sections was covered with special tissue-thin paper to absorb the old yellowed glue from a 19th century restoration. When the paper was peeled off, the newly vibrant color was protected with an adhesive made from a Japanese red algae called funori. Because the product is so expensive (one gram will run you 100 euros), the diagnostic laboratory of the Vatican Museums made their own extract directly from the imported seaweed. The restoration team then cautiously filled in areas of paint loss, reproducing the original materials used by the artists. The stucco was made from an ancient Roman recipe. The paints were all natural and free of chemicals.

The restoration took just under four years, double what it took Danti’s team to paint the Gallery of Maps in the first place. It has been open to the public this whole time. On Saturday, April 23rd, the Patrons were given a private showing of the restored Gallery.

There are some good views of the Hall and details of the restoration in progress in this Italian language video. The narration mainly gives a quick rundown of the history you’ve just read so I won’t repeat it, but you’ll find my translation of the interesting comments from Maria Ludmilla Pustka, head restorer of the paintings and wood artifacts of the Vatican Museums, below.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/7OtRQvnmiWE&w=430]

Maria Ludmilla Pustka: “The restoration of a work of art can be more complex than the original execution, and the great team we put together to make this restoration happen quickly had to use a very interesting, modern methodology that approaches a biorestoration. Thus nature itself has provided us with the proper materials for a better conservation.”

Narrator: “The restoration, which focused on the precarious condition of the plaster layer and the look of the painted surfaces, has also brought to light surprising discoveries.”

Pustka: “Every map has its own secret. Among the secrets, one new discovery was a coin of Urban VIII that was found inside a stucco relief, attesting to its date of manufacture. We also found a number of signatures from the original artists and past restorers.”