When side scan sonar found the wreck of an iron-hulled Civil War steamer off Oak Island, North Carolina, on February 27th, 2016, researchers from the Underwater Archaeology Branch of the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology identified it as one of three blockade runners known to have gone down in the area: the Agnes E. Fry, the Spunkie or the Georgianna McCaw. The measurements of the wreck suggested it was the Agnes E. Fry. The remains are 225 feet long, the Fry 236 feet long. The other two candidates were significantly smaller.

Archaeologists were hoping to get a conclusive identification when divers explored the site in March, but the currents were very active and visibility was consistently bad, maxing out at 18 inches on a good day. Divers were able to recover a few artifacts — a deck light, a coal sample and what appears to be the handle of a homemade knife — but nothing with a name. Still, the sonar and diving data clearly matched what we know about the Fry. Contemporary documents report that the two engines and paddlewheel were salvaged from the Fry. The engines and paddlewheel are missing from this wreck. At least one boiler is still in place, and it is of a newer type than McCaw or Spunkie were equipped with. The hull design is also more modern than the two other lost blockade runners. Damage to the bow and stern explains the small discrepancy in dimensions between the wreck and the Agnes E. Fry before it sank.

According to Billy Ray Morris, Deputy State Archaeologist and director of the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology’s Underwater Archaeology Branch, there are also references from the US Life Saving Service to this wreck being the Fry as late as the 1920s. Morris is “99.99% positive” on the wreck being the Fry, which is as convinced as anyone of a scientific bent can be.

The discovery made international news which spurred Capt. J.D. Thomas of the Charlotte Fire Department Special Operations/EMS Command to offer the Underwater Archaeology Branch the use of a state-of-the-art 3D sonar device provided by Nautilus Marine Group International, plus a team of experienced search and rescue divers to work with the maritime archaeologists. The 3D sonar technology allowed the team make a complete, highly accurate, multi-dimensional map of the wreck in days no matter how murky the waters. It also detects details that the side scanning sonar missed. This was the first 3D sonar imaging was used to scan a shipwreck site in North Carolina.

The results of the scan were combined into a sonar mosaic which shows the wreck in exceptional detail and high resolution. The Underwater Archaeology Branch has released the composite image complete with labels identifying the different parts of the ship and Billy Ray Morris was kind enough to send me a beautifully huge version of the mosaic.

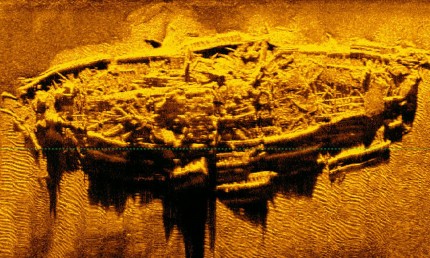

Here’s the original side scan sonar image, just for comparison.

Quite a difference, isn’t it? I can’t wait to see this technology widely applied to maritime archaeology.

The Agnes E. Fry was built and launched on the Clyde in Scotland in 1864. It was initially named the Fox, but Captain Joseph Fry renamed it after his beloved wife (and first cousin; their mothers were sisters), Agnes Evelina Fry, nee Sands. Captain Fry had had an illustrious career in the US Navy. He reluctantly resigned his commission when the Civil War broke out despite believing in the principle of the Union because he could not stand to fight against his home state of Louisiana and his family and friends. His skills as a naval captain were put to use in the Confederate Navy.

The Agnes E. Fry was built and launched on the Clyde in Scotland in 1864. It was initially named the Fox, but Captain Joseph Fry renamed it after his beloved wife (and first cousin; their mothers were sisters), Agnes Evelina Fry, nee Sands. Captain Fry had had an illustrious career in the US Navy. He reluctantly resigned his commission when the Civil War broke out despite believing in the principle of the Union because he could not stand to fight against his home state of Louisiana and his family and friends. His skills as a naval captain were put to use in the Confederate Navy.

In the Spring of 1864, he was sent to Scotland to pick up the new ship. He stopped in neutral Bermuda for supplies for the Confederacy and returned with his much-needed cargo to North Carolina where he tried seven times to get it through the Union blockade of Wilmington with no success. He finally broke through and on November 10th, 1864, wrote to his wife:

Many vessels have arrived here since I first left Bermuda, and it is also true that many have been lost trying to get in. God has watched over our safety, and prospered us wonderfully. I have been chased over and over again;… have had the yellow fever on board; have headed for the bar about seven times in vain. … I never was so happy in my life as when I at last arrived, and thought I should be with you in three or four days; nor so miserable as when I found they wanted me to try and go out again immediately, by which I lose my chance of coming home. But I am bound to do it. I am complimented on having the finest ship that ever came in, named, too, after her whom I love more than all the world beside. The owners are my personal friends, and are pledged to take care of you in my absence, or in case of my capture. She is a vessel they especially want me to command, and although I would not leave without having seen my family for twice her value, still duty requires that I should do so.

Blockade running required persistence and daring, and a strong, fast ship, all of which Joseph Fry had, but the latter not for long. The Agnes E. Fry ran aground near the mouth of the Cape Fear River on December 27th, 1864. Fry was given command of another ship in Mobile Bay until the end of the war.

Perhaps his time as a blockade runner gave him a taste for smuggling for a cause, because less than a decade after the Confederate surrender, he was commanding the steamer Virginius and bringing its cargo of rebels and weapons to Cuba to fight Spanish rule. He was captured by the Spanish before he got there and taken to Santiago de Cuba. Captain Fry and his crew were court-martialled on charges of piracy and convicted. Over the complaints of US and British officials, they were sentenced to death. On November 7th, 1873, Joseph Fry and 52 of his officers and crew were executed by firing squad in a brutally slapdash manner. A witness described the scene:

Perhaps his time as a blockade runner gave him a taste for smuggling for a cause, because less than a decade after the Confederate surrender, he was commanding the steamer Virginius and bringing its cargo of rebels and weapons to Cuba to fight Spanish rule. He was captured by the Spanish before he got there and taken to Santiago de Cuba. Captain Fry and his crew were court-martialled on charges of piracy and convicted. Over the complaints of US and British officials, they were sentenced to death. On November 7th, 1873, Joseph Fry and 52 of his officers and crew were executed by firing squad in a brutally slapdash manner. A witness described the scene:

“The victims were ranged facing the wall, and at a sufficient distance from it to give them room to fall forward. Captain Fry having asked for a glass of water, one was handed him by Charles Bell, the steward of the Morning Star. Fry then walked from the end of the line to the center, and calmly awaited his fate. He was the only man who dropped dead at the first volley, notwithstanding that the firing party were but ten feet away. Then ensued a horrible scene. The Spanish butchers advanced to where the wounded men lay writhing and moaning in agony, and, placing the muzzles of their guns in some in stances into the mouths of their victims, pulled the triggers, shattering their heads into fragments. Others of the dying men grasped the weapons thrust at them with a despairing clutch, and shot after shot was poured into their bodies before, death quieted them.”

Another 93 were scheduled to be shot, but the second round of executions was interrupted by Commander Sir Lambton Lorraine of the British warship Niobe who threatened to bombard the city if they didn’t stop. The execution of Joseph Fry caused outrage in the United States. President Ulysses S. Grant gave a speech to Congress decrying it as a barbaric slaughter in violation of treaties between the countries. Fry was seen as a martyr and patriot, and while things didn’t come to blows quite yet, fury over his fate still simmered 25 years later when war finally did break out between Spain and the United States.