More than two centuries after they were scattered, a medieval altarpiece, reliquaries and art works from the Premonstratensian convent of Altenberg in central Germany have been reunited at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum. Heaven on Display. The Altenberg Altar and Its Imagery brings together 37 precious devotional objects from the late 13th and early 14th centuries that have been in separate collections since Napoleon was cutting a swath through Europe.

More than two centuries after they were scattered, a medieval altarpiece, reliquaries and art works from the Premonstratensian convent of Altenberg in central Germany have been reunited at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum. Heaven on Display. The Altenberg Altar and Its Imagery brings together 37 precious devotional objects from the late 13th and early 14th centuries that have been in separate collections since Napoleon was cutting a swath through Europe.

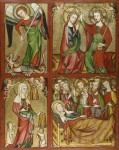

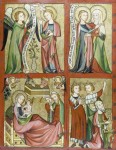

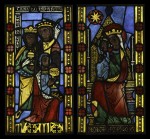

The star of the show is the Early Gothic Altenberg Altar, a folding high altar retable with a shrine cabinet, a polychrome statue of the Madonna and Child in the middle niche and painted panels on each side. The wings, some of the earliest surviving examples of German panel painting, are part the Städel’s permanent collection, but the rest is on loan. Other objects include reliquaries the once were kept in the shrine cabinet of the altarpiece, goldsmithery, 13th century altar crosses, figural glass paintings from an early 14th century window and two embroidered linen altar cloths made around 1330.

The star of the show is the Early Gothic Altenberg Altar, a folding high altar retable with a shrine cabinet, a polychrome statue of the Madonna and Child in the middle niche and painted panels on each side. The wings, some of the earliest surviving examples of German panel painting, are part the Städel’s permanent collection, but the rest is on loan. Other objects include reliquaries the once were kept in the shrine cabinet of the altarpiece, goldsmithery, 13th century altar crosses, figural glass paintings from an early 14th century window and two embroidered linen altar cloths made around 1330.

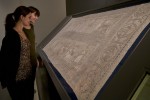

The altar cloths are large, elaborately decorated pieces that were placed on the altar in front of the retable. No other altar cloths from the Early Gothic period in Germany have survived.

The altar cloths are large, elaborately decorated pieces that were placed on the altar in front of the retable. No other altar cloths from the Early Gothic period in Germany have survived.

Sometime before 1192, Emperor Barbarossa granted the convent the status of imperial immediacy, which put it under the direct rule of the Holy Roman Emperor, exempting it from vassalage to the local lords, essentially a guarantee of independence. The daughters of area nobles joined the convent and endowments from their families over time transformed a small, obscure abbey into one of wealth and power.

One of those daughters was Gertrude, the child of St. Elizabeth of Hungary and Louis IV, Landgrave of Thuringia, who died a few months before Gertrude was born. After her beloved husband’s death, Elizabeth dedicated her life to asceticism and charitable works, so much so that she gave up basically everything in the world that she loved, including her children. Little Gertrude was two years old when she was sent to live with the canoness of Aldenberg. She took the veil and became cannoness herself when she was just 21. Her rule lasted until her death 49 years later.

One of those daughters was Gertrude, the child of St. Elizabeth of Hungary and Louis IV, Landgrave of Thuringia, who died a few months before Gertrude was born. After her beloved husband’s death, Elizabeth dedicated her life to asceticism and charitable works, so much so that she gave up basically everything in the world that she loved, including her children. Little Gertrude was two years old when she was sent to live with the canoness of Aldenberg. She took the veil and became cannoness herself when she was just 21. Her rule lasted until her death 49 years later.

Elizabeth was already dead by the time her daughter dedicated her own life to piety and mortification of the flesh, felled by a fever when she was 24 years old. Only five years later she was canonized. Gertrude collected relics of the mother she had only had childhood memories of, if any, for the abbey. The works on display are examples of Gertrude’s devotion to her literally sainted mother. There’s a tapestry from 1270 woven with scenes from the life of Elizabeth and Louis IV which may have been hung behind the altar on important occasions before the altarpiece was built, an arm reliquary shaped like an arm and containing an arm, Elizabeth’s silver jug and a ring that once belonged to Louis.

Elizabeth was already dead by the time her daughter dedicated her own life to piety and mortification of the flesh, felled by a fever when she was 24 years old. Only five years later she was canonized. Gertrude collected relics of the mother she had only had childhood memories of, if any, for the abbey. The works on display are examples of Gertrude’s devotion to her literally sainted mother. There’s a tapestry from 1270 woven with scenes from the life of Elizabeth and Louis IV which may have been hung behind the altar on important occasions before the altarpiece was built, an arm reliquary shaped like an arm and containing an arm, Elizabeth’s silver jug and a ring that once belonged to Louis.

The convent managed to retain its imperial status through the Reformation, the decline of imperial power and rise of the princes after the Thirty Years’ War. It came to an end with the Final Recess of 1803 when Napoleon compensated German princes who had lost lands west of the Rhine to France with ecclesiastical territories. Altenberg, monastery, church and extensive agricultural and forested lands, became the personal property of the Princes of Solms-Braunfels who had long coveted it. They turned the convent into a summer residence and distributed its works of art and devotional objects throughout their castles. The altar went to Braunfels Castle, the arm reliquary of St. Elisabeth to the chapel of Sayn Palace.

The convent managed to retain its imperial status through the Reformation, the decline of imperial power and rise of the princes after the Thirty Years’ War. It came to an end with the Final Recess of 1803 when Napoleon compensated German princes who had lost lands west of the Rhine to France with ecclesiastical territories. Altenberg, monastery, church and extensive agricultural and forested lands, became the personal property of the Princes of Solms-Braunfels who had long coveted it. They turned the convent into a summer residence and distributed its works of art and devotional objects throughout their castles. The altar went to Braunfels Castle, the arm reliquary of St. Elisabeth to the chapel of Sayn Palace.

From there they made their way into museums and collections around the world. The Städel Museum in got the wings of the altar in 1925. Other collections including those of the city of Frankfurt, Munich’s Bayerische Nationalmuseum, the Hermitage in St Petersburg and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City all have bits and pieces of Altenberg. It’s an impressive feat reuniting so many elements of the medieval convent to put the objects in some semblance of their original context.

From there they made their way into museums and collections around the world. The Städel Museum in got the wings of the altar in 1925. Other collections including those of the city of Frankfurt, Munich’s Bayerische Nationalmuseum, the Hermitage in St Petersburg and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City all have bits and pieces of Altenberg. It’s an impressive feat reuniting so many elements of the medieval convent to put the objects in some semblance of their original context.

The exhibition is on right now and runs through September 25th, 2016.