The first lock of hair from the head of third President of the United States and author of the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson ever to be offered at public auction sold on Saturday, May 14th, for $6,875 including the buyer’s premium. You might think for that amount you’d get traditional tuft of hair, maybe tied in a ribbon or encased in a velvet-lined box, but no. There are precisely 14 reddish hairs in this lot, held in a glassine envelope. They look like he got some tape stuck on his hair and had to pull it off losing a few in the process.

The first lock of hair from the head of third President of the United States and author of the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson ever to be offered at public auction sold on Saturday, May 14th, for $6,875 including the buyer’s premium. You might think for that amount you’d get traditional tuft of hair, maybe tied in a ribbon or encased in a velvet-lined box, but no. There are precisely 14 reddish hairs in this lot, held in a glassine envelope. They look like he got some tape stuck on his hair and had to pull it off losing a few in the process.

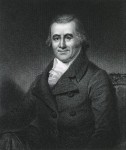

The ownership history of these hairs is well documented with a clear connection to Thomas Jefferson, which is why they sold at more than double the pre-sale estimate of $3,000, already a princely sum for 14 hairs. Locks of hair were common keepsakes in the 18th and 19th centuries, and several of Thomas Jefferson’s are extant. None of them are known to have been sold at auction before, however. The first owner of the hairs (save for Jefferson himself when they were attached to his scalp) was Doctor Robley Dunglison who was very close to Jefferson in the last year and a half of his life.

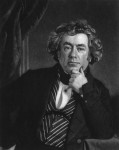

Robley Dunglison was an English doctor trained as a general practitioner and obstetrician. He was working at the Eastern Dispensary in Whitechapel, London, in 1824 when he met Francis Walker Gilmer, a lawyer and friend of Thomas Jefferson’s and the first chair of law at the University of Virginia. The university had been founded in 1817 and was just about to open its doors to students (the first class would meet on March 7th, 1825), but first they had to find some professors. Jefferson commissioned Gilmer to recruit faculty in Britain. Gilmer offered Dunglison a positioning heading the anatomy and medicine department and Dunglison accepted, in no small part because it gave him the wherewithal to marry his sweetheart Harriette Leadam. They married on October 5th, 1824, and on October 27th they set sail for Virginia.

Robley Dunglison was an English doctor trained as a general practitioner and obstetrician. He was working at the Eastern Dispensary in Whitechapel, London, in 1824 when he met Francis Walker Gilmer, a lawyer and friend of Thomas Jefferson’s and the first chair of law at the University of Virginia. The university had been founded in 1817 and was just about to open its doors to students (the first class would meet on March 7th, 1825), but first they had to find some professors. Jefferson commissioned Gilmer to recruit faculty in Britain. Gilmer offered Dunglison a positioning heading the anatomy and medicine department and Dunglison accepted, in no small part because it gave him the wherewithal to marry his sweetheart Harriette Leadam. They married on October 5th, 1824, and on October 27th they set sail for Virginia.

By the terms of his contract with UVA, Dunglison was prohibited from establishing a private practice which made him the first professional full-time professor of medicine in the United States. There was one exception: he was allowed to treat Thomas Jefferson who was by then 81 and in very poor health. For most of his life Jefferson had avoided doctors, believing most illnesses naturally sorted themselves out. He explored his thinking on the subject in an 1807 letter to Dr. Caspar Wistar, the country’s foremost anatomist and professor of anatomy, midwifery, and surgery at the University of Pennsylvania.

As far as Jefferson was concerned, physicians were more often than not ill-informed quacks randomly experimenting on patients only to worsen the problem, delay the healing and/or take credit for any improvement that would have happened anyway if they’d just been left alone. “I believe we may safely affirm that the inexperienced and presumptuous band of medical tyros let loose upon the world destroys more of human life in one year than all the Robinhoods, Cartouches, and Macheaths do in a century,” he wrote. (Cartouche was the nickname of the famous highwayman Louis Dominique Bourguignon who stole from the rich and gave to the poor in early 18th century France. He was captured and executed by breaking on the wheel in 1721.)

As far as Jefferson was concerned, physicians were more often than not ill-informed quacks randomly experimenting on patients only to worsen the problem, delay the healing and/or take credit for any improvement that would have happened anyway if they’d just been left alone. “I believe we may safely affirm that the inexperienced and presumptuous band of medical tyros let loose upon the world destroys more of human life in one year than all the Robinhoods, Cartouches, and Macheaths do in a century,” he wrote. (Cartouche was the nickname of the famous highwayman Louis Dominique Bourguignon who stole from the rich and gave to the poor in early 18th century France. He was captured and executed by breaking on the wheel in 1721.)

Jefferson thought enough of the young Dunglison to overcome his reluctance. Dunglison first treated him for an obstructive uropathy, probably caused by an enlarged prostate, by passing a bougie. Jefferson paid close attention, taking notes on the remedies Dunglison recommended and learning how to pass the bougie himself. After that bonding experience, Dunglison became Jefferson’s personal physician and was a frequent visitor at Monticello from then on and was at Jefferson’s deathbed on the Fourth of July, 1826.

The lock the 14 hairs came from passed from Dr. Robley Dunglison to his son Dr. Richard J. Dunglison, editor of the first five American editions of Gray’s Anatomy. It was then passed down to his step-son Charles Ferry Fisher, a librarian of the Philadelphia College of Physicians. Most of the lock was donated to the college along with other Robley Dunglison artifacts, but they kept a few of the hairs. Those few hairs were eventually acquired by autograph dealer Charles Hamilton.

The lock the 14 hairs came from passed from Dr. Robley Dunglison to his son Dr. Richard J. Dunglison, editor of the first five American editions of Gray’s Anatomy. It was then passed down to his step-son Charles Ferry Fisher, a librarian of the Philadelphia College of Physicians. Most of the lock was donated to the college along with other Robley Dunglison artifacts, but they kept a few of the hairs. Those few hairs were eventually acquired by autograph dealer Charles Hamilton.

A 1929 affidavit from Charles Ferry Fisher attesting to the provenance of the hairs was included with the lot, as is another letter from Charles Hamilton confirming its authenticity. It’s not known when the lock was snipped. Since it’s still the reddish hair of Jefferson’s younger days — he was fully grey by the time of his death — Dr. Dunglison was likely given it to remember his most famous patient by rather than taking it himself.