Archaeologists have found evidence of homegrown grapes in late Iron Age and Viking Denmark: two charred grape seeds unearthed from a site on the west shore of Lake Tissø, Western Zealand. This is one of the richest sites from the late Germanic Iron Age and Viking Age ever discovered in Denmark. Since the 1990s, excavations have unearthed two aristocratic residences (one dating to 550–700 A.D., the second to 700–1050 A.D.), pit houses, assembly places, a market and artisan workshop area and ritual sites.

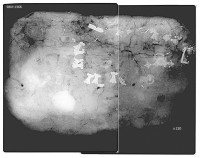

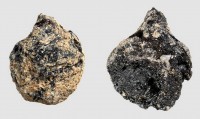

In the 2012-2013 dig season, the team collected soil samples for macrofossil analysis from both the aristocratic residences. In 2015, archaeobotanist and curator at the National Museum Peter Steen Henriksen recovered one charred seed while sifting through a five liter soil sample from Bulbrogård, the oldest of the royal complexes. Examining it under the microscope, Henriksen could see that it looked like a grape seed; the charring had not altered its shape. A colleague confirmed the identification. It was indeed a seed from the common grapevine (Vitis vinifera). He found a second grape seed in a soil sample taken from the later royal complex, Fugledegård.

In the 2012-2013 dig season, the team collected soil samples for macrofossil analysis from both the aristocratic residences. In 2015, archaeobotanist and curator at the National Museum Peter Steen Henriksen recovered one charred seed while sifting through a five liter soil sample from Bulbrogård, the oldest of the royal complexes. Examining it under the microscope, Henriksen could see that it looked like a grape seed; the charring had not altered its shape. A colleague confirmed the identification. It was indeed a seed from the common grapevine (Vitis vinifera). He found a second grape seed in a soil sample taken from the later royal complex, Fugledegård.

Before this find, the earliest grape seeds found in Denmark date to the late Middle Ages, and historical records from the 13th century support that grapes were grown in Denmark during the medieval warm period. Because this was such an exceptional discovery, the grape seeds were studied in further detail. Each seed was subjected to archaeobotanical analysis. One of them, the one from Fugledegård was radiocarbon tested. The C14 result dated it to between 780 and 980 A.D., the Viking Age. The Bulbrogård was not dated because researchers wanted to preserve it for strontium isotope analysis. (The testable cores of the seeds are so small it wasn’t possible to run both tests on each.) The strontium isotope results placed the grape seed squarely in the range characteristic for Denmark, specifically Zealand.

They are by far the oldest grape seeds discovered in Denmark, and the first potential evidence of local viticulture in late Iron Age/Viking Age Denmark. There’s no way to confirm the seeds were used to grow grapes at Lake Tissø. They could have been in the lees of a wine barrel, although that would not explain how the seeds were found in two complexes that were 600 meters and at least a hundred years apart. Besides, it’s hardly an import if the raw material was grown on the island.

They are by far the oldest grape seeds discovered in Denmark, and the first potential evidence of local viticulture in late Iron Age/Viking Age Denmark. There’s no way to confirm the seeds were used to grow grapes at Lake Tissø. They could have been in the lees of a wine barrel, although that would not explain how the seeds were found in two complexes that were 600 meters and at least a hundred years apart. Besides, it’s hardly an import if the raw material was grown on the island.

“This is the first discovery and sign of wine production in Denmark, with all that that entails in terms of status and power. We do not know how [the grapes] were used – it may have been just to have a pretty bunch of grapes decorating a table, for example – but it is reasonable to believe that they made wine,” archaeological botanist and museum curator Peter Steen Henriksen of Denmark’s National Museum told Videnskab.dk. […]

“Before we only had suspicions, but now we can see that they actually had grapes and therefore the resources to produce [wine] themselves. Suddenly it all becomes very real,” professor Karin Margarita Frei of the National Museum told Videnskab.dk.

The results of the study have been published in the Danish Journal of Archaeology and can be read here.