The Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon) was one of the many animals in the Egyptian bestiary that figures in tomb decorations going back to the Old Kingdom. They were depicted mainly in hunting scenes, stalking their prey in the swampy riverlands, climbing a papyrus stalk to snatch hatchlings from a nest, feasting on a fish in the rushes, even attacking a goose mid-flight.

They are easily recognizable in this context and from the animal’s characteristic features — short legs, long tail, long body, short snout and small ears — but divorced from its natural setting, one depiction of a mongoose has been the subject of debate for more than a century. A new field study of wall paintings in the cemetery of Beni Hassan has identified an Egyptian mongoose being led on a leash in the 11th Dynasty tomb of Baqet I (Tomb 29). This is the only known depiction of a mongoose on a leash in ancient Egyptian art.

They are easily recognizable in this context and from the animal’s characteristic features — short legs, long tail, long body, short snout and small ears — but divorced from its natural setting, one depiction of a mongoose has been the subject of debate for more than a century. A new field study of wall paintings in the cemetery of Beni Hassan has identified an Egyptian mongoose being led on a leash in the 11th Dynasty tomb of Baqet I (Tomb 29). This is the only known depiction of a mongoose on a leash in ancient Egyptian art.

Beni Hassan is a Middle Kingdom (21st to 17th centuries B.C.) cemetery about 12 miles south of the modern city of Minya in Middle Egypt. There are almost a thousand rock-cut and shaft tombs in the cemetery. The rock-cut tombs are carved into the limestone cliff face that overlooks the lower part of the cemetery where the shaft tombs are located. The elite, mainly hereditary nomarchs (regional governors) were buried in the upper cemetery, their rock-cut tombs elaborately decorated with animals and scenes from daily life (wrestling, chipping flint tools, spinning, playing music, pot making, smelting, feeding oryxes).

Several of the decorated tombs were documented by Egyptologists in the 19th century, including luminaries of the field like Jean-François Champollion and, most notably, Scottish pioneer Robert Hay, who undertook the first exceptionally thorough project to illustrate, trace and draw every ancient Egyptian tomb and temple he encountered in the 1820s and 30s. By the time of British Egyptologist Percy Newberry’s expedition to Beni Hassan in 1890, the paintings in one of the tombs Hay had documented (Tomb 3) were so faded and damaged that Newberry had to rely on Hay’s 60-year-old work in his own publications. Newberry’s team made important new tomb discoveries and meticulously illustrated every painting found, tracing them in full-size or drawing them from life. One of the draughtsmen on that team was a young Howard Carter. Newberry would be part of his team 30 years later when Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Several of the decorated tombs were documented by Egyptologists in the 19th century, including luminaries of the field like Jean-François Champollion and, most notably, Scottish pioneer Robert Hay, who undertook the first exceptionally thorough project to illustrate, trace and draw every ancient Egyptian tomb and temple he encountered in the 1820s and 30s. By the time of British Egyptologist Percy Newberry’s expedition to Beni Hassan in 1890, the paintings in one of the tombs Hay had documented (Tomb 3) were so faded and damaged that Newberry had to rely on Hay’s 60-year-old work in his own publications. Newberry’s team made important new tomb discoveries and meticulously illustrated every painting found, tracing them in full-size or drawing them from life. One of the draughtsmen on that team was a young Howard Carter. Newberry would be part of his team 30 years later when Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Newberry noted the unusual image of the leashed animal in his reports, suggesting it might be a mongoose, but other scholars disagreed with his identification. The Egyptian Antiquities Ministry team has recently conserved and cleaned the Beni Hassan tombs, and Professor Linda Evans of Macquarie University in Australia has surveyed the refreshed paintings using the latest technology.

The conservation and recording has “revealed many scenes not found in Newberry’s reports,” wrote Evans. In addition, the new work has identified creatures in the drawings that Newberry had been uncertain about. […]

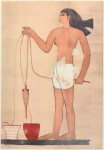

Evans’ team determined that the animal is “morphologically identical” to the Egyptian mongoose, wrote Evans, noting that the animal is also clearly depicted on a leash. “The animal clearly sports a gray collar that tapers to join a long, gray leash, which is held in the left hand of a bearer, who also holds the leash of a spotted hunting dog situated below the mongoose,” Evans said. […]

“While mongooses have never been fully domesticated — that is, subjected to controlled breeding — some cultures have chosen to keep the animals as pets in order to control unwanted pests, such as snakes, rats and mice,” Evans wrote.

Evans speculates that the mongoose could have been used the way some bird dogs are used today, to scare birds out of the bush so hunters can have at them. That’s one possibility, but there’s no reason they couldn’t have been used to stalk and catch prey as well.

My grandmother told me that her mother, my very formidable great-grandmother who was reputedly a crack shot, used to hunt rabbits with ferrets. Their long, tubular bodies easily fit into warrens, and they had an implacable drive to get to the other side of whatever tunnel they were in and to kill whatever might be in their way. They’d clear a warren in no time, keeping the rabbit population under control and providing the family with much-needed food.

My grandmother told me that her mother, my very formidable great-grandmother who was reputedly a crack shot, used to hunt rabbits with ferrets. Their long, tubular bodies easily fit into warrens, and they had an implacable drive to get to the other side of whatever tunnel they were in and to kill whatever might be in their way. They’d clear a warren in no time, keeping the rabbit population under control and providing the family with much-needed food.

I had pet ferrets at the time, which is what inspired the story-telling, and according to my grandmother they bore only superficial resemblance to the ones my great-grandmother used for ferreting. The hunters were much larger and much, much meaner. My guys were sweet and cute and funny with the vestiges of that powerful prey drive turned into quirky, charming behaviors like stealing keys out of guest’s purses and hiding them under the bed. That’s because they were fully domesticated, bearing as much relation to their wild cousins as that tabbycat on your lap does to a serval. Maybe the ancient Egyptians went mongoosing just like my great-grandmother went ferreting. (People still use ferrets to hunt today, btw, especially in the UK.)