James Cook’s detailed exploration and mapping of New Zealand and eastern Australia during his first voyage (1766-1771) would overshadow the more limited Dutch efforts from more than a century earlier, but the first Europeans to sight and make landfall on the Australian continent and surrounding islands were the Dutch. The first European to step foot on Australia was Willem Janszoon in 1606, although in keeping with the fine tradition of European explorers he had no idea where he was, thinking he was in southern New Guinea. He mapped some of the coastline and made contact with the pointy end of the indigenous people — ten of his men died in the process — but like his compatriots who followed, he didn’t explore thoroughly.

James Cook’s detailed exploration and mapping of New Zealand and eastern Australia during his first voyage (1766-1771) would overshadow the more limited Dutch efforts from more than a century earlier, but the first Europeans to sight and make landfall on the Australian continent and surrounding islands were the Dutch. The first European to step foot on Australia was Willem Janszoon in 1606, although in keeping with the fine tradition of European explorers he had no idea where he was, thinking he was in southern New Guinea. He mapped some of the coastline and made contact with the pointy end of the indigenous people — ten of his men died in the process — but like his compatriots who followed, he didn’t explore thoroughly.

The Dutch never attempted settlement. Their aims were strictly pecuniary. The Dutch East India Company (VOC), always on the lookout for new lands with the apparently limitless gold, silver and precious gemstones of a Mexico or Peru, received a report from one of their operatives in Japan that he’d heard speak of a country to the south rich with gold. In 1639, the VOC’s Governor-General Antonio van Diemen sent two ships to find this El Dorado of the Pacific. One of them, the Engel, was captained by Abel Tasman. They searched for six months, going as far as 2,000 miles from Japan, 1,000 miles further into the North Pacific than any other European explorer before them, but were unsuccessful.

The Dutch never attempted settlement. Their aims were strictly pecuniary. The Dutch East India Company (VOC), always on the lookout for new lands with the apparently limitless gold, silver and precious gemstones of a Mexico or Peru, received a report from one of their operatives in Japan that he’d heard speak of a country to the south rich with gold. In 1639, the VOC’s Governor-General Antonio van Diemen sent two ships to find this El Dorado of the Pacific. One of them, the Engel, was captained by Abel Tasman. They searched for six months, going as far as 2,000 miles from Japan, 1,000 miles further into the North Pacific than any other European explorer before them, but were unsuccessful.

But the dreams of diving into bottomless vaults of gold like unto Scrooge McDuck never die, and people had been positing that there had to be an unknown large land mass in the Pacific, the Terra Australis Incognita, since antiquity. The discovery of South America ramped up excitement at the prospect of the Terra Australis because philosophically geographers imagined the world had to have some kind of symmetry, so the new continent needed something to balance it out on the other side of the globe.

But the dreams of diving into bottomless vaults of gold like unto Scrooge McDuck never die, and people had been positing that there had to be an unknown large land mass in the Pacific, the Terra Australis Incognita, since antiquity. The discovery of South America ramped up excitement at the prospect of the Terra Australis because philosophically geographers imagined the world had to have some kind of symmetry, so the new continent needed something to balance it out on the other side of the globe.

The VOC sent Tasman out again to find the South Land in August of 1642. His brief was to look south of New Guinea this time, and should he find the new world and make contact with the locals, he was to use the mercantile goods his ships were laden with to trade for gold and silver. Van Diemen’s instructions on this point were clear:

“Keep them ignorant of the value of the same, appear as if you were not greedy for them; and if gold or silver is offered in any barter, you must feign that you do not value those metals, showing them copper, zinc and lead, as if those minerals were of more value to us.”

On November 24th, the crew sighted land. From Tasman’s journal of the voyage:

This land being the first land we have met with in the South Sea and not known to any European nation we have conferred on it the name of Anthoony Van Diemenslandt in honour of the Honourable Governor-General, our illustrious master, who sent us to make this discovery; the islands circumjacent, so far as known to us, we have named after the Honourable Councillors of India….

That island is now known as Tasmania. From there he traveled southeast, sighting what we know as South Island, New Zealand, on December 13th. He named it Staten Landt because he thought it was connected to Stateneiland, Argentina, on the tip of South America. His attempts to make contact with the indigenous people didn’t go well. The Maori were not interested in whatever stuff he had in his cargo hold. They greeted him by attacking his ship and killing four of his men.

That island is now known as Tasmania. From there he traveled southeast, sighting what we know as South Island, New Zealand, on December 13th. He named it Staten Landt because he thought it was connected to Stateneiland, Argentina, on the tip of South America. His attempts to make contact with the indigenous people didn’t go well. The Maori were not interested in whatever stuff he had in his cargo hold. They greeted him by attacking his ship and killing four of his men.

After that, Tasman got out of Dodge City with a quickness and headed back to Batavia. He did a little more charting on the way — Tonga, Fiji — but no landing and no contact. On a second voyage in 1644, he made it to Australia, mapping the north coast, but that was the extent it. Seven months after he left, he was back in Batavia.

The VOC was disappointed, to say the least. He found no new trade routes, no new markets for Dutch goods, and worst of all, no gold. He didn’t even do much in the way of exploring or mapping, not that that was any kind of priority for the VOC beyond its usefulness in enabling profitable trade. They thought Tasman had been too timid for the job. The next person they sent to the South Land would be bolder. Only there was no next person, not a Dutch one, anyway. The next person would be the Englishman James Cook 120 years later.

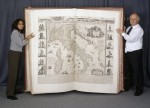

Until Cook, it was the Dutch who had the most information about Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania and the East Indies, and not coincidentally, Dutch maps were considered the cream of the crop in the 17th century. In 1659, Joan Blaeu, official Cartographer to the Dutch East India Company, used all of the VOC’s private records of the exploration of the Terra Australis from Janszoon to Tasman to create a great wall map of Australia, its surrounding islands and Southeast Asia. This would be the first map to label Australia “Nova Hollandia.” “Nova Zeelandia” and some of van Diemen’s Land make an appearance too.

Until Cook, it was the Dutch who had the most information about Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania and the East Indies, and not coincidentally, Dutch maps were considered the cream of the crop in the 17th century. In 1659, Joan Blaeu, official Cartographer to the Dutch East India Company, used all of the VOC’s private records of the exploration of the Terra Australis from Janszoon to Tasman to create a great wall map of Australia, its surrounding islands and Southeast Asia. This would be the first map to label Australia “Nova Hollandia.” “Nova Zeelandia” and some of van Diemen’s Land make an appearance too.

This map is so rare there are only two known copies complete with Blaeu’s imprint and side panels describing the lands on the map. One of the two (dimensions: 158.7 x 117.4cm) has been rediscovered in an Italian villa where it has remained unrestored in its original condition since at least the 19th century. It is going under the hammer at Sotheby’s Travel, Atlases, Maps & Natural History sale on May 9th in London, along with a second Joan Blaeu wall map, this one of Asia (117 x 155cm), in equally good condition.

This map is so rare there are only two known copies complete with Blaeu’s imprint and side panels describing the lands on the map. One of the two (dimensions: 158.7 x 117.4cm) has been rediscovered in an Italian villa where it has remained unrestored in its original condition since at least the 19th century. It is going under the hammer at Sotheby’s Travel, Atlases, Maps & Natural History sale on May 9th in London, along with a second Joan Blaeu wall map, this one of Asia (117 x 155cm), in equally good condition.

Richard Fattorini, Sotheby’s Director in Books and Manuscripts said: “It is wonderful to find a pair of wall maps in their original unrestored condition, retaining the linen and rollers as decorated for an early, or possibly the first, owner. Wall-maps, by their very nature, are susceptible to damage; mounted on a linen backing, with wooden rods, suspended on a wall, they could be subjected to careless handling, sunlight, heat, damp and soot. They often have a very poor survival rate as, once damaged or geographically superseded, they were readily discarded. As a consequence, they are often found in a frail state.”

There are some holes, tears and damage with loss of small parts of the drawing and text, but all in all, these are near-miraculous survivals. Because of its seminal importance in the history of cartography and exploration, the Australia map is estimated to sell for 200,000-250,000 GBP ($248,320-310,400). The map of Asia is a comparative steal at 60,000-80,000 GBP ($74,496-99,328).

There are some holes, tears and damage with loss of small parts of the drawing and text, but all in all, these are near-miraculous survivals. Because of its seminal importance in the history of cartography and exploration, the Australia map is estimated to sell for 200,000-250,000 GBP ($248,320-310,400). The map of Asia is a comparative steal at 60,000-80,000 GBP ($74,496-99,328).

An excerpt from Blaeu’s commentary on the Australia wall map:

“Papas landt or Nova Guinea, Nova Hollandia, discovered in the year 1644, Nova Zeelandia or New Zealand reached in 1642, Antoni van Diemens land found in the same year, Carpentaria, thus named after General Carpentier, and still other lands, partly discovered are shown in this map. But of all these and of the above-mentioned islands we cannot speak more fully because of the want of space; nor has there yet been published anything, or little concerning these last named; wherefor the reader and spectator must rest content with this map, until I. [Joan] Blaeu, shall publish these and the aforesaid a large book, full of maps and descriptions, which is at present being prepared.”

Less than a year later, a group of Dutch merchants compiled a book full of Blaeu’s wall maps as a gift for King Charles II in honor of his restoration to the throne. It is indeed a large book. A very, very large book.

Less than a year later, a group of Dutch merchants compiled a book full of Blaeu’s wall maps as a gift for King Charles II in honor of his restoration to the throne. It is indeed a large book. A very, very large book.