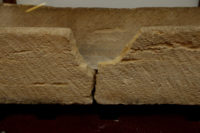

On Friday, August 4th, visitors to the Prittlewell Priory Museum in Southend, Essex, did something so stupid and reckless it defies understanding. Parents of a young child lifted him over the barrier into a medieval sandstone sarcophagus, presumably to capture a precious memory of their cherub desecrating a funerary artifact. As anyone with two neurons to rub together could have predicted, the coffin was knocked off its stand. The impact cracked the fragile sandstone down the middle and took a chunk out of the floor of the coffin.

Museum staff discovered the damage later that day because in addition to being irresponsible numbskulls, the parents are also craven cowards who hightailed it out of the museum as quickly as their chicken legs could carry them without notifying anyone to the havoc they’d wreaked. Curators only found out what had happened by reviewing CCTV footage from security cameras.

“The care of our collections is of paramount importance to us and this isolated incident has been upsetting for the museums service, whose staff strive to protect Southend’s heritage within our historic sites,” said Claire Reed, the conservator responsible for repairing the sarcophagus.

“My priority is to carefully carry out the treatment needed to restore this significant artefact so it can continue to be part of the fascinating story of Prittlewell Priory.”[…]

The sandstone casket that was damaged is the last of its kind. “It’s a very important artefact and historically unique to us as we don’t have much archaeology from the priory,” said Reed.

Conservators are currently assessing the damage, but at first glance they expect it should be able to be repaired without breaking the bank. The council thinks it might take fewer than £100 ($130). Suitable materials for restoring historical artifacts can be expensive, however, and then there’s the cost that will be incurred by creating a new display for the coffin when it goes back on display. For its own protection, it will have to be completely enclosed, so museum visitors will have to pay in distance and separation from the artifact for the carelessness of two idiots.

Conservators are currently assessing the damage, but at first glance they expect it should be able to be repaired without breaking the bank. The council thinks it might take fewer than £100 ($130). Suitable materials for restoring historical artifacts can be expensive, however, and then there’s the cost that will be incurred by creating a new display for the coffin when it goes back on display. For its own protection, it will have to be completely enclosed, so museum visitors will have to pay in distance and separation from the artifact for the carelessness of two idiots.

Founded in around 1110 A.D. by Robert FitzSuen as the Priory of St Mary, a cell of the Cluniac Priory of St Pancras in Lewes, Sussex, Prittlewell was a small monastery with fewer than 20 monks at any given time. Most of the medieval priory was destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. That and later construction is why archaeological material from the original priory is so sparse. Henry VIII granted the monastery, its lands and revenues to Thomas Audley, Lord Chancellor of England and Keeper of the Great Seal, who also scored a number of far larger and more valuable monastic estates in the wake of the Dissolution.

Prittlewell remained in private hands until the early 20th century. The Scratton family made the most pronounced mark on the estate in the Victorian era, extensively renovating, rebuilding and adding to what was left of the medieval monastery to create an impressive and livable country home. Having lived in the era before Poltergeist, they created a walled kitchen garden over what had been the monks’ burial ground. The inevitable hauntings ensued and visitors have reported seeing a ghostly monk wandering the halls of the former cloister.

Prittlewell remained in private hands until the early 20th century. The Scratton family made the most pronounced mark on the estate in the Victorian era, extensively renovating, rebuilding and adding to what was left of the medieval monastery to create an impressive and livable country home. Having lived in the era before Poltergeist, they created a walled kitchen garden over what had been the monks’ burial ground. The inevitable hauntings ensued and visitors have reported seeing a ghostly monk wandering the halls of the former cloister.

In 1917 Prittlewell Priory, the buildings, the 22-acre property and six adjacent acres were bought from Captain Scratton by prosperous local jeweler and benefactor Robert Arthur Jones. He donated the whole kit and caboodle to the city of Southend with the explicit intent that it be turned into a multi-use public facility for the benefit of the people of Southend. Jones explained his reasoning at the time:

“I think it is a sin for a man to die rich, it is a great privilege to me to be able to do this, for I believe strongly in facilities for recreation. There will now be no need for such an out of the way and costly park as Belfairs. Prittlewell, with its historic and old-world associations, its beautiful trees and lakes, and its nearness to the centre of town, is an ideal place. Part of the building would be suitable for a museum, and there would also be refreshment room accommodation, while the grounds would provide facilities for cricket, football, tennis, hockey and other sports. I propose that the name of the park should be Priory Park”

In 1922 Prittlewell Priory opened as Southend’s first museum and Priory Park as its first public park. The damaged sarcophagus was unearthed near the former priory church in 1921 during the archaeological exploration of the site that accompanied its conversion into the museum and park. It contained a skeleton, likely the remains of senior monk because a stone coffin was an expensive object that would have been used for brothers of high rank.

In 1922 Prittlewell Priory opened as Southend’s first museum and Priory Park as its first public park. The damaged sarcophagus was unearthed near the former priory church in 1921 during the archaeological exploration of the site that accompanied its conversion into the museum and park. It contained a skeleton, likely the remains of senior monk because a stone coffin was an expensive object that would have been used for brothers of high rank.