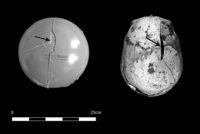

Archaeologists surveying a site in Drumnadrochit by Loch Ness in Scotland have discovered a 4,000-year-old cist grave. There were no human remains in the stone-lined pit because it had become filled with soil and any organic materials decayed into nothingness, but there was a single carinated beaker found intact on the cobbled floor. The geometric decoration of the pot identified it as dating to and 2200-1900 B.C.

Archaeologists surveying a site in Drumnadrochit by Loch Ness in Scotland have discovered a 4,000-year-old cist grave. There were no human remains in the stone-lined pit because it had become filled with soil and any organic materials decayed into nothingness, but there was a single carinated beaker found intact on the cobbled floor. The geometric decoration of the pot identified it as dating to and 2200-1900 B.C.

The find is all the more significant because it’s not the only one. Another cist burial was unearthed on land adjacent to the current site in January 2015 after archaeologists were called in on an urgent salvage mission. Workers building a new health center in Drumnadrochit raised a large stone slab and found a stone-lined burial cist containing human skeletal remains in a crouched position. Preliminary study assessed the bones to date to the Bronze Age and a full archaeological excavation ensued. It revealed a partial skeleton of an adult. The remains weren’t in great condition, but three feet away from the inhumation, archaeologists found an oval pit with sherds from a beaker.

These were the first Bronze Age artifacts and human remains found in the location between the Coilte and Enrick rivers. At the time, archaeologists thought that might be significant, that the proximity to an ancient river channel made the site appealing to Bronze Age people as a site for funerary ritual. The area has long since been drained to make way for farming and it’s likely that centuries of agricultural activity damaged any other burials. The discovery of the intact beaker pot in a cist, even without a body, supports the contention that the spot had special meaning 4,000 or so years ago.

These were the first Bronze Age artifacts and human remains found in the location between the Coilte and Enrick rivers. At the time, archaeologists thought that might be significant, that the proximity to an ancient river channel made the site appealing to Bronze Age people as a site for funerary ritual. The area has long since been drained to make way for farming and it’s likely that centuries of agricultural activity damaged any other burials. The discovery of the intact beaker pot in a cist, even without a body, supports the contention that the spot had special meaning 4,000 or so years ago.

Mary Peteranna, Operations Manager for AOC Archaeology’s Inverness office, said: “The discovery of a second Bronze Age cist on the site provides increasing evidence for the special selection of this site in the prehistoric landscape as a location for ceremonial funerary activity.

“This cist, along with the medical centre cist and a second burial pit, is generating much more information about the prehistory of Glen Urquhart.”

Mrs Peteranna added: “Historically, there was a large cairn shown on maps of the area but you can imagine that centuries of ploughing in these fields have removed any upstanding reminders of prehistoric occupation.

“During the work, we actually found a displaced capstone from another grave that either has not survived or has not yet been discovered. So it’s quite likely that these graves were covered by stone cairns or mounds, long-since ploughed out.”