An archaeological excavation at the historic site of Avery’s Rest in Rehoboth Bay, Delaware, has unearthed the skeletal remains of some of Delaware’s earliest colonists. The inhumation burials of 11 individuals interred in the late 1600s include three of African descent, one of them a child. These are the earliest known remains of enslaved people ever discovered in Delaware.

An archaeological excavation at the historic site of Avery’s Rest in Rehoboth Bay, Delaware, has unearthed the skeletal remains of some of Delaware’s earliest colonists. The inhumation burials of 11 individuals interred in the late 1600s include three of African descent, one of them a child. These are the earliest known remains of enslaved people ever discovered in Delaware.

Seven of the eight individuals of European descent were neatly buried in a single row. The three African Americans — two adult men and one child of about five years of age at time of death — were interred near the seven but in a separate section. Black and white were all buried in coffins, although only the nails have survived. The people of African descent were not related to each other and their mitochondrial DNA places their ancestral origins in west, central and east Africa. Most of their lives, if not all of them, were spent in the mid-Atlantic area of what is now the United States. Rehoboth Bay was wilderness then, and officially part of Pennsylvania and therefore a Dutch colony.

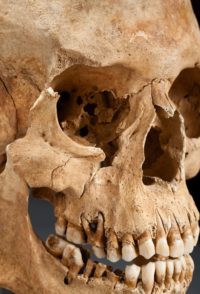

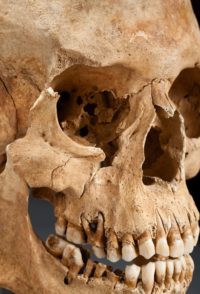

The hardship of their lives was writ large on their bones. One of the people of African descent, an adult male about 35 years of age, received a blow to the head so severe it chipped a piece of bone off his right eyebrow and fractured his face. Experts believe it wasn’t likely to be the strike that killed him, but it did happen at the time of his death and likely contributed to it. His spine showed signs of heavy labour and his front teeth have grooves from where he bit down hard on his clay pipe while doing all that heavy labour. All of the remains show signs of copious dental issues: cavities, abscesses, extractions. One petite 4’11” adult woman was missing all but six of her teeth.

The hardship of their lives was writ large on their bones. One of the people of African descent, an adult male about 35 years of age, received a blow to the head so severe it chipped a piece of bone off his right eyebrow and fractured his face. Experts believe it wasn’t likely to be the strike that killed him, but it did happen at the time of his death and likely contributed to it. His spine showed signs of heavy labour and his front teeth have grooves from where he bit down hard on his clay pipe while doing all that heavy labour. All of the remains show signs of copious dental issues: cavities, abscesses, extractions. One petite 4’11” adult woman was missing all but six of her teeth.

Avery’s Rest is listed in the National Register of Historic Places because it was part of the vast 800-acre property of Captain John Avery who moved to Rehoboth Bay from Maryland in 1675 shortly after the colony changed hands from the Dutch to the British. A ship’s captain in Maryland, he grew his plantation into a major agricultural and livestock concern, planing corn, wheat and most of all, tobacco. There is evidence of a peach orchard on the property as well, some of the first peach trees imported to what would become the United States.

John Avery became a very wealthy and prominent community leader in Delaware, attaining the rank of captain in the militia and receiving an appointment as Justice of the Peace of Whorekill Court in 1678. He doesn’t seem to have endeared himself to many in the role; he was frequently reported for going into rages and showering his fellow justices with abusive language. He was said to have beaten one of them with a cane. They didn’t have long to put up with his irascibility. Avery died in 1682, leaving his plantation to his wife and three children. His will and estate inventories list 50 head of cattle, other assorted livestock, tools, furniture and two humans bound in chattel slavery valued at 3,000 pounds of tobacco apiece.

John Avery became a very wealthy and prominent community leader in Delaware, attaining the rank of captain in the militia and receiving an appointment as Justice of the Peace of Whorekill Court in 1678. He doesn’t seem to have endeared himself to many in the role; he was frequently reported for going into rages and showering his fellow justices with abusive language. He was said to have beaten one of them with a cane. They didn’t have long to put up with his irascibility. Avery died in 1682, leaving his plantation to his wife and three children. His will and estate inventories list 50 head of cattle, other assorted livestock, tools, furniture and two humans bound in chattel slavery valued at 3,000 pounds of tobacco apiece.

Despite its significant history as a very early plantation owned by a first-generation English colonist and its including on the National Register, in 2005 the site was acquired by real estate developers to build housing. The Archaeological Society of Delaware and the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs asked the developers allow them to dig a trench or two on the off-chance there might be some archaeological material from the earliest days of European and African presence in Delaware and the developers magnanimously granted them permission to excavate the site in 2006 and 2007. Construction, and the attendant destruction of anything left unexcavated, went forward after that, but the teams continued to explore neighboring land.

The teams excavating the site were hoping to find the remains of the main house Captain Avery and his family lived in, but they never did. By 2007, they had found wells, one wooden well lining (preserved in the waterlogged environment), fence lines, clay pits, glass beads, numerous pipe bowls, Spanish coins, metal pieces from horse fittings, assorted pottery and a large number of animal bones, likely left behind during the process of butchering all that stock mentioned in the estate documents for trade, not for family consumption.

These were meaningful discoveries from a social historical perspective, providing researchers with a rare opportunity to explore the day-to-day operations of an early colonial plantation that was large and prosperous enough to anchor the trade and supply of the British residents of the New World colony. They weren’t the structures the archaeologists had been hoping for, however, so over the next few years they kept looking for them on adjoining properties.

In 2012, they found something else entirely: the first human remains. That triggered a legal requirement that next-of-kin be sought to grant state permission to excavate and study the remains. Three Avery descendants stepped up and granted said permission. By September of 2014, 11 bodies had been unearthed and the Smithsonian Institution’s experts were on the ground to recover the remains and move them to the Smithsonian laboratory for thorough analysis.

In 2012, they found something else entirely: the first human remains. That triggered a legal requirement that next-of-kin be sought to grant state permission to excavate and study the remains. Three Avery descendants stepped up and granted said permission. By September of 2014, 11 bodies had been unearthed and the Smithsonian Institution’s experts were on the ground to recover the remains and move them to the Smithsonian laboratory for thorough analysis.

So thorough was it that the analysis has taken three years to complete. The age, gender, ethnic origin of the decedents are now known, with even more detail to come.

“Avery’s Rest provides a rare opportunity to learn about life in the 17th century, not only through the study of buried objects and structures, but also through analyses of well-preserved human skeletal remains,” said Dr. Owsley, who leads the Division of Physical Anthropology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. “The bone and burial evidence provides an intriguing, personal look into the life stories of men, women and children on the Delaware frontier, and adds to a growing body of biological data on the varied experiences of colonist and enslaved populations in the Chesapeake region.”

Bone and DNA analysis confirmed that three of the burials were people of African descent and eight were of European descent. Coupled with research from the historical record, Dr. Owsley further determined that the European burials may be the extended family of John Avery and his wife Sarah, including their daughters, sons-in-law and grandchildren. However, genetic markers alone are not sufficient to determine the exact identities of the remains. […]

The remains will stay in the custody of the Smithsonian, where they will assist ongoing work to trace the genetic and anthropological history of the early colonial settlers of the Chesapeake region. Delaware law strictly forbids the public display of human remains.

While the Smithsonian works the science, Delaware, the Archaeological Society and other historical organizations are launching a research project in the hopes of discovering the identities of the 11 people found buried at Avery’s Rest. Any information they uncover would become part of an exhibition, be it names, places, dates or facial reconstructions.

“Delaware’s history is rich, fascinating and deeply personal to many of us who call this state home,” said Secretary of State Jeff Bullock. “Discoveries like this help us add new sharpness to our picture of the past, and I’m deeply grateful to the passionate community of historians, scientists and archeologists who have helped bring these new revelations to light.”

The expansion of the subway system in Los Angeles, California, has an unexpected commonality with Rome’s tortured endeavors to build a new line through the historic center: the ground under these cities is crammed full of the remains of the current residents’ predecessors. In Rome’s case it’s ancient archaeological materials, while Los Angeles’ specialty is Ice Age fossils. The company that has LA’ contract for digging the new tunnels keeps a paleontologist on call at all times so that whenever they find something, which is often, it can be properly handled and recovered by a professional. It’s a state regulatory requirement that has ensured the protection of cultural and natural historic patrimony since subway construction first began the 1990s, an attempt to right the many wrongs done to Los Angeles’ history and prehistory during its earlier spurts of rapid growth.

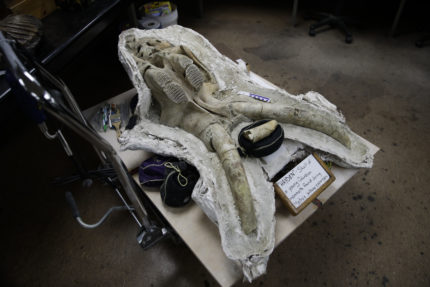

The expansion of the subway system in Los Angeles, California, has an unexpected commonality with Rome’s tortured endeavors to build a new line through the historic center: the ground under these cities is crammed full of the remains of the current residents’ predecessors. In Rome’s case it’s ancient archaeological materials, while Los Angeles’ specialty is Ice Age fossils. The company that has LA’ contract for digging the new tunnels keeps a paleontologist on call at all times so that whenever they find something, which is often, it can be properly handled and recovered by a professional. It’s a state regulatory requirement that has ensured the protection of cultural and natural historic patrimony since subway construction first began the 1990s, an attempt to right the many wrongs done to Los Angeles’ history and prehistory during its earlier spurts of rapid growth. The latest fossil bumper crop has been springing up since 2014 when construction on the extension of the Metro Purple Line started. Paleontologist Ashley Leger of Cogstone Resource Management (CGM) was contracted to examine any finds made by work crews excavating tunnels. Whenever they found something, they’d stop what they were doing, call her and move over to another location to continue work on the project. That gave her the space she needed while still keeping the extension on some semblance of a schedule. The construction crews even pitch in when help is needed.

The latest fossil bumper crop has been springing up since 2014 when construction on the extension of the Metro Purple Line started. Paleontologist Ashley Leger of Cogstone Resource Management (CGM) was contracted to examine any finds made by work crews excavating tunnels. Whenever they found something, they’d stop what they were doing, call her and move over to another location to continue work on the project. That gave her the space she needed while still keeping the extension on some semblance of a schedule. The construction crews even pitch in when help is needed.The next morning, Leger knelt at the site and recognized what appeared to be a partial elephant skull.

From there, the skull was hauled a mile or so to Los Angeles’ La Brea Tar Pits and Museum, home to one of America’s most fossil-rich sites.