A small wrapped mummy believed to be a hawk in the Egyptian collection of the Maidstone Museum in Kent, England, has been revealed to instead contain the complete remains of a severely deformed stillborn baby or late-term fetus. The mummy was labelled “EA 493 – Mummified Hawk Ptolemaic Period,” a conclusion drawn from its cartonnage outer wrapping which was painted to look like a bird. Its shape and size was comparable to other hawks and the birds held great religious symbolism in traditional Egyptian polytheism so were mummified in large numbers.

A small wrapped mummy believed to be a hawk in the Egyptian collection of the Maidstone Museum in Kent, England, has been revealed to instead contain the complete remains of a severely deformed stillborn baby or late-term fetus. The mummy was labelled “EA 493 – Mummified Hawk Ptolemaic Period,” a conclusion drawn from its cartonnage outer wrapping which was painted to look like a bird. Its shape and size was comparable to other hawks and the birds held great religious symbolism in traditional Egyptian polytheism so were mummified in large numbers.

It was first CT scanned in 2016 when the Museum received a grant to create a new display space for its Egyptian and Greek artifacts. The star of the museum’s Egyptian collection, the mummy of Ta-Kush, the only adult human mummy in Kent, would take pride of place in the new gallery, so the museum undertook to examine Ta-Kush in greater detail, working with the Kent Institute of Medicine and Science to CT scan the mummy and with FaceLab at Liverpool John Moores University to create a facial reconstruction based on the scan.

All 30 of the mummies in the collection were also CT scanned, including the ostensible hawk. That first scan revealed that it was no hawk at all, but rather a tiny, probably fetal, human. The clinical CT scanner could not capture the remains in sufficient detail for a thorough examination because of their minute size. The museum contacted mummy expert Andrew Nelson of Western University in Ontario, and he arranged with

Nikon Metrology (UK) to conduct a micro-CT scan at a resolution 10 times higher than the clinical CT scan.

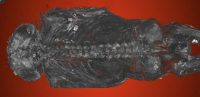

The scans produced are some of the highest-resolution images of a mummy ever taken, and by far the highest-resolution images of a mummified fetus. Nelson and a multi-disciplinary international team of experts analyzed the scans. They found that the mummy was a stillborn male at 23 to 28 weeks gestation who was severely anencephalic, a malformation in which the fetus’ skull and brain never develop properly.

The scans produced are some of the highest-resolution images of a mummy ever taken, and by far the highest-resolution images of a mummified fetus. Nelson and a multi-disciplinary international team of experts analyzed the scans. They found that the mummy was a stillborn male at 23 to 28 weeks gestation who was severely anencephalic, a malformation in which the fetus’ skull and brain never develop properly.

The images show well-formed toes and fingers but a skull with severe malformations, says Nelson, a bioarchaeologist and professor of anthropology at Western. “The whole top part of his skull isn’t formed. The arches of the vertebrae of his spine haven’t closed. His earbones are at the back of his head.”

There are no bones to shape the broad roof and sides of the skull, where the brain would ordinarily grow. “In this individual, this part of the vault never formed and there probably was no real brain,” Nelson says.

That makes it one of just two anencephalic mummies known to exist (the other was described in 1826), and by far the most-studied fetal mummy in history. […]

The research provides important clues to the maternal diet – anencephaly can result from lack of folic acid, found in green vegetables – and raises new questions about whether mummification in this case took place because fetuses were believed to have some power as talismans, Nelson says.

“It would have been a tragic moment for the family to lose their infant and to give birth to a very strange-looking fetus, not a normal-looking fetus at all. So this was a very special individual,” Nelson says.

There are only nine mummies of human fetuses known to exist and this is the only anencephalic one to have been scientifically studied. It is a unique find and of great archaeological significance, much more so than the mummy of Ta-Kush which launched the project. It wasn’t going to go on display in the new gallery; it will be an important part of it now.