The formal name of what has become known as the Ghent Altarpiece is the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. The central panel of the massive 18-panel polyptych painted by Jan and Hubert van Eyck for the Saint Bavo Cathedral depicts the Lamb of God on an altar, encircled by kneeling angels. A symbol of the sacrifice of Christ, the Lamb has a wound on its chest which gushes a thick stream of blood into a chalice. Adoring the Lamb in four distinct groups are prophets, apostles, saints, popes and assorted church figures, martyrs, the Righteous Judges and Warriors of Christ.

The formal name of what has become known as the Ghent Altarpiece is the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. The central panel of the massive 18-panel polyptych painted by Jan and Hubert van Eyck for the Saint Bavo Cathedral depicts the Lamb of God on an altar, encircled by kneeling angels. A symbol of the sacrifice of Christ, the Lamb has a wound on its chest which gushes a thick stream of blood into a chalice. Adoring the Lamb in four distinct groups are prophets, apostles, saints, popes and assorted church figures, martyrs, the Righteous Judges and Warriors of Christ.

It is the only panel on the altarpiece that is horizontal and at 134.3 x 237.5 cm (4’5″ x 7’10”), it is as wide as the three vertically oriented panels above it.

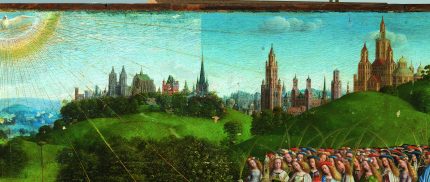

As with the other panels in the altarpiece, the Adoration of the Lamb was awkwardly overpainted. First some small wanna-be restorations to areas of the panel were done and then, in the middle of the 16th century, just over a hundred years after the masterpiece was completed in 1432, a more ambitious refurbishment was undertaken to correct the earlier interventions and fill in paint loss. The result of this was that 45% of the central panel was overpainted. The Lamb was the primary victim of this well-meaning assault. The background landscape — the sky, the hills and the spires of New Jerusalem — and the altar cloth and draped robes suffered most of the remaining blows.

As with the other panels in the altarpiece, the Adoration of the Lamb was awkwardly overpainted. First some small wanna-be restorations to areas of the panel were done and then, in the middle of the 16th century, just over a hundred years after the masterpiece was completed in 1432, a more ambitious refurbishment was undertaken to correct the earlier interventions and fill in paint loss. The result of this was that 45% of the central panel was overpainted. The Lamb was the primary victim of this well-meaning assault. The background landscape — the sky, the hills and the spires of New Jerusalem — and the altar cloth and draped robes suffered most of the remaining blows.

A 1951 restoration removed some of the overpaint on the head of the Lamb, but again the good intentions wound up as pavers on the road to Hell. When the green overpaint around the head was removed, the original smaller ears of the Lamb were revealed and since restorers didn’t remove the 16th century Dumbo ears, the poor fella looked to have four ears.

A 1951 restoration removed some of the overpaint on the head of the Lamb, but again the good intentions wound up as pavers on the road to Hell. When the green overpaint around the head was removed, the original smaller ears of the Lamb were revealed and since restorers didn’t remove the 16th century Dumbo ears, the poor fella looked to have four ears.

Overpaint, faulty restorations, the misfortunes of war, fire, moisture, climate and everything else that can possibly happen to a giant icon of late medieval art had left all of the panels in dire need of thorough conservation. A major conservation and restoration project saw the first eight panels removed to the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts in 2012 where experts from the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) began the slow, painstaking process of returning the Ghent Altarpiece as close as possible to its original splendor.

Overpaint, faulty restorations, the misfortunes of war, fire, moisture, climate and everything else that can possibly happen to a giant icon of late medieval art had left all of the panels in dire need of thorough conservation. A major conservation and restoration project saw the first eight panels removed to the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts in 2012 where experts from the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) began the slow, painstaking process of returning the Ghent Altarpiece as close as possible to its original splendor.

That project continues today, and KIK-IRPA conservators are now working on the central panel, the very core of the altarpiece. Thankfully, they found that despite all the interference over the years, almost all of the original Van Eyck paint layers remained intact under the mess. Only 3% was lost. That allowed them to painstakingly remove all of the later overpaint and reveal the panel as the Van Eycks originally created it.

That project continues today, and KIK-IRPA conservators are now working on the central panel, the very core of the altarpiece. Thankfully, they found that despite all the interference over the years, almost all of the original Van Eyck paint layers remained intact under the mess. Only 3% was lost. That allowed them to painstakingly remove all of the later overpaint and reveal the panel as the Van Eycks originally created it.

After intensive research, the restoration team of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Brussels) has removed the old overpaint that masked the main figure of the Ghent Altarpiece for nearly five centuries. As such, the well-known Lamb – an impassive and rather neutral figure, with a wide forehead and large ears – has given way to Van Eyck’s original. With its intense gaze this medieval Lamb, characterized by a graphically defined snout and large frontal eyes, draws the viewer into the scene of His ultimate sacrifice.[…]

While removing the overpaint – a delicate operation carried out under the microscope with surgical scalpels – the restorers discovered a subtly shaded sky with streaks of clouds above graceful mountains. The original buildings, overpainted with greyish layers, were painted in a variety of colours, with a beautiful play of light. Even previously hidden buildings are emerging

from beneath the much simpler overpaint at the horizon. Solid-coloured garments make place for luminous draperies with complex folds defined by delicate highlights and deep shadows.

The seemingly bizarre choice of making  the Lamb of God look like an expressionless animal was a function of the 16th century tastes in painting. The powerful gaze directed straight at the viewer of Van Eyck’s original humanized the Lamb, conveying its identification with Jesus. The more realistically lamb-like overpainted version, its entrancingly human eyes replaced with small prey animal eyes on the sides of its head, was more in keeping with 16th century conventions.

the Lamb of God look like an expressionless animal was a function of the 16th century tastes in painting. The powerful gaze directed straight at the viewer of Van Eyck’s original humanized the Lamb, conveying its identification with Jesus. The more realistically lamb-like overpainted version, its entrancingly human eyes replaced with small prey animal eyes on the sides of its head, was more in keeping with 16th century conventions.

The restoration is ongoing so it’s only on view to the public at the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts during the weekends. On weekdays conservators get full custody of the panel. It needs to be laid flat for this stage of the conservation, so it can’t be seen by visitors to the museum.