An international team of researchers has studied the bones of 85 individuals from the 12th and 13th centuries afflicted with extremely severe cases of leprosy. Isolated and shunned in life as victims of an infectious disease that causes visible disfigurement and deformity, leprosy sufferers were isolated in death too, buried in a dedicated cemetery. The skeletons were excavated from the leprosarium cemetery of St. George in Odense, Denmark, in the early 1980s and are now stored at the University of Southern Denmark.

Out of the 85 individuals from the Odense cemetery tested, 69 contained sufficient nuclear DNA to yield genotype data and those 69 also tested positive for the presence of the bacterium. The genetic material was compared against 223 skeletons from the same period unearthed in Denmark and Northern Germany that showed no evidence of leprosy infection. That makes this is the first case-control study relying on ancient DNA.

Out of the 85 individuals from the Odense cemetery tested, 69 contained sufficient nuclear DNA to yield genotype data and those 69 also tested positive for the presence of the bacterium. The genetic material was compared against 223 skeletons from the same period unearthed in Denmark and Northern Germany that showed no evidence of leprosy infection. That makes this is the first case-control study relying on ancient DNA.

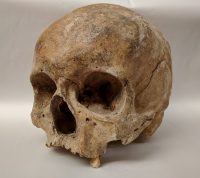

There are no automated systems for analyzing ancient DNA. Researchers had to manually remove any impurities from the Odense DNA and analyze the cleaned samples. They were able to examine 50-100 milligrams of material extracted from the teeth and hard bones of the skull. From that material they extracted up to 5% human DNA and several parts-per-thousand of leprosy DNA. For an ancient DNA study, those are really high yields, possible only because of the excellent state of preservation of the remains.

As a result of the analyses, researchers discovered that one particular variant of the HLA-DRB1 gene, whose job is to recognize bacteria and trigger an immune response, notably fell down on the job when it came to leprosy. Its presence made people more susceptible to it. The isolation that people with leprosy were subjected to had one upside: it made it much less likely that they’d have children to whom they could pass down the HLA-DRB1 variant. This might have contributed to the ultimate demise of the disease in Europe.

Scientists do not know precisely when and how the disease first came to Europe, but the crusades reached their peak between 1200 and 1400 CE, just when Boldsen’s research suggests that half of the population in the worst hit areas were dying with the disease.

Leprosy was almost wiped out in Denmark and large parts of Europe during the 1500s. But why it disappeared is a big question, says Bygbjerg,

“You might assume that the disease disappeared because the bacteria behind leprosy changed and became less dangerous. But the study shows that this is not the case,” he says.

The HLA variant also plays a role in inflammatory and autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes, so the study of medieval leprosy may prove to have far wider implications, adding to our knowledge of the development of diseases that plague so many people today.

The HLA variant also plays a role in inflammatory and autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes, so the study of medieval leprosy may prove to have far wider implications, adding to our knowledge of the development of diseases that plague so many people today.

The bacterial genome sequencing revealed that leprosy victims in medieval Odense were afflicted by more than one strain of bacteria. Researchers have sequenced 10 complete leprosy genomes attesting to how complex leprosy infection was in 12th and 13th century Odense. As leprosy is not native to Denmark, carriers brought multiple strains into the area. This find came as a surprise as researchers previous knew of only one strain of Mycobacterium leprae in the area.

The study has been published in the journal Nature Communications and can be read in its entirety free of charge here.