The intense radiation and light of the particle accelerator has done it again. We’ve already seen synchrotron X-rays read a long-erased Galen text, map the molecular composition of cannon balls from the Mary Rose and virtually open a heavily corroded 17th century box to reveal the medallions within in jaw-dropping detail. Now we can add daguerreotypes tarnished beyond recognition to the synchrotron’s ever-expanding abilities to resuscitate the fatalities of time.

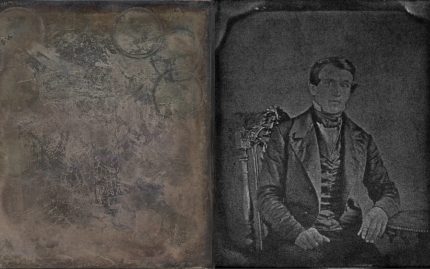

The daguerreotypes in question belong to the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) in Ottawa, Ontario. Taken in the 19th century, they were so corroded and marred that all that was visible of one of them was a ghostly outline while the other was a hacked up Kandinsky abstract with not even the ghost of the sitter remaining. Their terrible condition made them ideal subjects for a new study on the chemical changes that cause daguerreotype degradation.

Daguerreotypes were made by exposing silver plates to iodine vapour and waiting for minutes until the vapour had made the plate light-sensitive enough to capture the image. The photographer would then develop the picture by exposing the plate to mercury vapour. A solution of sodium thiosulfate cleaned the plate of excess iodine leaving a stable image on the plate.

Pinpointing the smallest trace of chemical residue is what synchrotron technology does best. Over the past three years, researchers from Western University in London, Canada, analyzed damaged daguerreotypes at the Canadian Light Source (CLS). Findings published last year and earlier this year revealed the chemical compositions of different manifestations of tarnish, but the most recent report takes a great leap forward to reveal the people underneath.

This preliminary research at the CLS led to today’s paper and the images [lead study author and Western University phD candidate Madalena] Kozachuk collected at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source where she was able to analyze the daguerreotypes in their entirety.

Kozachuk used rapid-scanning micro-X-ray fluorescence imaging to analyze the plates, which are about 7.5 cm wide, and identified where mercury was distributed on the plates. With an X-ray beam as small as 10×10 microns (a human scalp hair averages 75 microns across) and at an energy most sensitive to mercury absorption, the scan of each daguerreotype took about eight hours.

“Mercury is the major element that contributes to the imagery captured in these photographs. Even though the surface is tarnished, those image particles remain intact. By looking at the mercury, we can retrieve the image in great detail,” said Tsun-Kong (T.K.) Sham, Western’s Canada Research Chair in Materials and Synchrotron Radiation. He also is a co-author of the research and Kozachuk’s supervisor.

This research will contribute to improving how daguerreotype images are recovered when cleaning is possible and will provide a way to seeing what’s below the tarnish if cleaning is not possible.

The identity of the two people whose images have been recovered is unknown. One is a woman, the other a man, and both daguerreotypes are early examples, perhaps dating as early as 1850. The plate of the woman was bought at a garage sale and that’s all the NGC knows about it. There’s no information at all about the fella.

The full study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports and can be read free of charge online.