During the European witch panics of the 16th and 17th century, more than 800 people were accused of witchcraft in Norway. Three hundred of them were found guilty and executed. The last to die in central Norway was one of the most pathetic victims and the domino effect of her case resulted in the longest and most widespread witch hunt in Trondheim. It dragged on for three years after her execution and ensnared more than 30 people.

Her name was Kirsten Iversdatter. She was a Sámi woman (the people historically known as Lapplanders) who drifted from town to town in the Gauldalen valley of Trøndelag county, begging for food and threatening people with curses when she was refused. She was commonly known as Finn-Kirsten, a reference to her Sámi origin. Her ethnicity played a large part in the fear she struck in the hearts of the locals, for the Sámi were reputed to have connections to the demonic world so powerful that not even the power of Christ could compel.

Her name was Kirsten Iversdatter. She was a Sámi woman (the people historically known as Lapplanders) who drifted from town to town in the Gauldalen valley of Trøndelag county, begging for food and threatening people with curses when she was refused. She was commonly known as Finn-Kirsten, a reference to her Sámi origin. Her ethnicity played a large part in the fear she struck in the hearts of the locals, for the Sámi were reputed to have connections to the demonic world so powerful that not even the power of Christ could compel.

They could summon the spirits of their ancestors and gods of nature with their magical drums (the so-called ‘rune-drum’), enabling them to both see the future and divine news from distant places. Their percussive magic could find lost items and influence fortunes in life and business. Historical sources tell us that Norwegian farmers would pay the Sami for such magical services, but that one should be wary of their company. If one incurred the wrath of a Sami, so the Norwegians believed, the Sami could release a gand, an evil spirit and/or a physical object, which had the power to strike a man dead, even to split mountains.

So when Kirsten muttered imprecations or quickly appeared and disappeared in doorways, people got scared. Next thing you know, cows’ milk dried up, crops failed, family members got sick, horses died and Kirsten was blamed for it.

On February 18th, 1674, Kirsten was arrested in the village of Støren on suspicion of witchcraft. She was charged with harming people and animals in Gauldalen valley. She denied engaging in witchcraft, casting spells or causing any harm. In the absence of a confession, they came up with other charges that were more easily proven. The chaplain and villagers testified that she never went to church, which was a crime in those days. She also had two daughters, one 20, one two years old, neither of which were born in legitimate wedlock. Fornication was a crime too. So Finn-Kirsten was convicted of skipping church and having extra-marital sex and was condemned to die by beheading.

Her ordeal was far from over. Støren’s bailiff Jens Randulf had a reputation for being adept as getting witches to talk. His methods, one can imagine, were as brutal as they were effective. Even after denying the charges in her first trial and even though she was already condemned to death, Jens was so good at torturing her that she confessed to everything and more. She had “given herself to the Devil” who appeared to her as a dog. She traveled the mountains around Støren with Satan and his other human disciples, local ones this time.

Now that they had their confession, Kirsten’s previous infractions took a back seat and the witch trial started.

After this new confession, the case was transferred to Trondheim Court of Appeal. Finn-Kirsten was detained in ‘Kongsgården’ (the King’s royal palace) in Trondheim city – today known as the Archbishop’s Palace – under the custody of the county governor Joachim Vind. After torture and interrogation by Vind and the public officers of Støren, she named more than thirty people as accomplices, ranging from both wealthy and poor in Trondheim to prominent farmers in the valley of Gauldalen. Amongst other things, Finn-Kirsten ‘confessed’ that the son of Inger Rognessen had visited Hell three times; she claimed that another woman called Inger (who lived by the city bridge) had levitated through air with her, and that she knew both white magic and sorcery. Finn-Kirsten also claimed that Inger was eager to become an apprentice of the Devil, but that she refused her the same ‘honour’ as she had only served Satan for two years. Guri, a carpenter’s wife, was alleged to have been ridden into the mountains to meet the devil twice, but Finn-Kirsten could not say if Guri was the rider or if someone rode her! This was the end for Finn-Kirsten. Her punishment was increased from beheading to death by burning, as the statutes against witchcraft allowed[.]

On October 12, 1674, a great fire was set alight by the city gates of Trondheim. Kirsten was tied to a ladder and tipped into the fire. A large crowd watched her burn to death. As she had confessed to witchcraft, her estate was forfeit. The court records describe this estate as “a few ragged clothes,” a sad testament to a life of poverty ended in brutal fashion.

Of the people she named under torture as co-witches, three of them were put on trial, including one Gjertrud Berdal who like so many “witches” was an herbalist who made home remedies for people (and their animals). Her most notable tool of witchcraft was apparently the ability to magically milk the cream of people’s cows so when they milked their cows all they got was skim. Neither Gjertrud nor the other two were convicted.

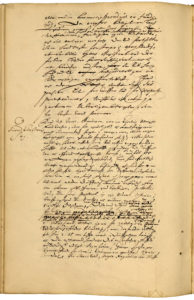

Even though it lasted years and marked the conclusion of the witch frenzy in central Norway, the trial of Kirsten Iversdatter and its aftermath was soon forgotten. Other burned witches became folk heroes of sorts. The story of Finn-Kirsten was rediscovered and published in 2014 after Norwegian University of Science and Technology researcher Ellen Alm found surviving accounts of her case in Norwegian court records and county financial statements from the 1670’s.