Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main compound in cannabis that causes its psychoactive effects, residue has been discovered on braziers in a burial ground in western China. The graves where the braziers were found date to 500 B.C., making them the oldest evidence of cannabis being smoked for consciousness-altering purposes.

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main compound in cannabis that causes its psychoactive effects, residue has been discovered on braziers in a burial ground in western China. The graves where the braziers were found date to 500 B.C., making them the oldest evidence of cannabis being smoked for consciousness-altering purposes.

There is evidence of the cannabis plant being used for its oil and fibers going back 4,000 years, but not that it was cultivated, and wild cannabis has negligible quantities of THC. Cannabis plants have been found in burials dating to between 2,400 and 2,800 years ago in China’s Turpan Basin indicating a ritual significance, but again, there is no evidence of them having been consumed in any way.

It’s unclear from the archaeological record when cannabis began to be selectively bred and cultivated to enhance its psychoactive properties. The first historical account of the use of inhaled cannabis is in Herodotus’ Histories. In Book IV, he describes a Scythian king’s funeral thus:

Such, then, is the mode in which the kings are buried: as for the people, when any one dies, his nearest of kin lay him upon a waggon and take him round to all his friends in succession: each receives them in turn and entertains them with a banquet, whereat the dead man is served with a portion of all that is set before the others; this is done for forty days, at the end of which time the burial takes place. After the burial, those engaged in it have to purify themselves, which they do in the following way. First they well soap and wash their heads; then, in order to cleanse their bodies, they act as follows: they make a booth by fixing in the ground three sticks inclined towards one another, and stretching around them woollen felts, which they arrange so as to fit as close as possible: inside the booth a dish is placed upon the ground, into which they put a number of red-hot stones, and then add some hemp-seed.

Hemp grows in Scythia: it is very like flax; only that it is a much coarser and taller plant: some grows wild about the country, some is produced by cultivation: the Thracians make garments of it which closely resemble linen; so much so, indeed, that if a person has never seen hemp he is sure to think they are linen, and if he has, unless he is very experienced in such matters, he will not know of which material they are.

The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy, and this vapour serves them instead of a water-bath; for they never by any chance wash their bodies with water.

Herodotus lived around 484 – 425 B.C. and is believed to have written The Histories between 440 and 430 B.C. So far, this thin sourcing is the most historians have had to go on regarding the origins of the inhalation of psychoactive cannabis in Eurasia.

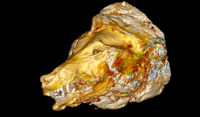

Researchers unearthed 10 wooden braziers containing stones with traces of burning from eight graves at the Jirzankal Cemetery in the eastern Pamir mountains. Using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), researchers tested samples of organic material from 10 brazier fragments and four of the stones inside the braziers. They found cannabis biomarkers on all the wooden vessels, on nine of the vessels’ burned residues and on two of the four stones. This is strong evidence that cannabis plants were burned by placing them on hot stones inside wooden braziers.

Researchers unearthed 10 wooden braziers containing stones with traces of burning from eight graves at the Jirzankal Cemetery in the eastern Pamir mountains. Using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), researchers tested samples of organic material from 10 brazier fragments and four of the stones inside the braziers. They found cannabis biomarkers on all the wooden vessels, on nine of the vessels’ burned residues and on two of the four stones. This is strong evidence that cannabis plants were burned by placing them on hot stones inside wooden braziers.

Not only that, but the cannabinoids found in the braziers contained higher levels of cannabinol (CBN), the oxidative metabolite of THC, than of cannabidiol (CBD), which is not psychotropic. If the plants burned had been wild, the levels of CBN and CBD would be roughly equivalent. The greater levels of the former indicate this was a plant either recognized and foraged as being a better high, or deliberately cultivated for it.

Some of the skeletons recovered from the site, situated in modern-day western China, have features that resemble those of contemporaneous peoples further west in Central Asia. Objects found in the burials also appear to link this population to peoples further west in the mountain foothills of Inner Asia. Additionally, stable isotope studies on the human bones from the cemetery show that not all of the people buried there grew up locally.

These data fit with the notion that the high-elevation mountain passes of Central and Eastern Asia played a key role in early trans-Eurasian exchange. Indeed, the Pamir region, today so remote, may once have sat astride a key ancient trade route of the early Silk Road. The Silk Road was at certain times in the past the single most important vector for cultural spread in the ancient world. Robert Spengler, the lead archaeobotanist for the study, also at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, explains, “The exchange routes of the early Silk Road functioned more like the spokes of a wagon wheel than a long-distance road, placing Central Asia at the heart of the ancient world. Our study implies that knowledge of cannabis smoking and specific high-chemical-producing varieties of the cannabis plant were among the cultural traditions that spread along these exchange routes.”

The study has been published in the journal Science Advances and can be read in its entirety here.