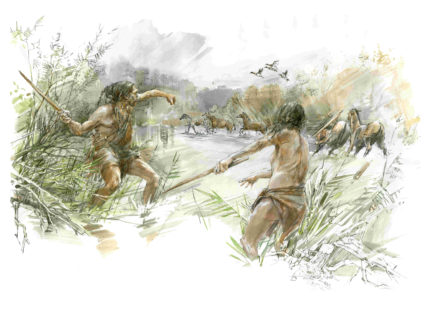

Prehistoric remains were first discovered in the open-cast lignite mine near the town of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany, in 1992. Over time 13 distinct Paleolithic find sites have been unearthed at Schöningen which was the shoreline of a lake 300,000 years ago and replete with wildlife. Mammal, fish and bird remains, man-made stone tools and wooden weapons indicate that Homo heidelbergensis, the pre-Neanderthal early humans living in the area at the time, took full advantage of the natural resources available at the lake’s edge. More than 10,000 animal bones, almost all of them horse bones, found there bear cutting marks from the animals having been butchered with sharp stone tools.

Prehistoric remains were first discovered in the open-cast lignite mine near the town of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany, in 1992. Over time 13 distinct Paleolithic find sites have been unearthed at Schöningen which was the shoreline of a lake 300,000 years ago and replete with wildlife. Mammal, fish and bird remains, man-made stone tools and wooden weapons indicate that Homo heidelbergensis, the pre-Neanderthal early humans living in the area at the time, took full advantage of the natural resources available at the lake’s edge. More than 10,000 animal bones, almost all of them horse bones, found there bear cutting marks from the animals having been butchered with sharp stone tools.

The waterlogged soil and the thick layered depositions of silt and mud created ideal conditions for the preservation and dating of archaeological material. In 1994, archaeologists discovered a wooden throwing stick (a rod with a pointed end hurled at prey to injure them or direct their movement) in layer 13/11, sedimentary sequence 4. Seven more throwing spears were found there over the next four years. Dating to between 337,000 and 300,000 years old, these are the oldest known intact hunting weapons from prehistoric Europe.

In December 2016, archaeologists from the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment unearthed a new throwing stick in layer 13/11-4. Like all but one of its predecessors, it was made of spruce wood. It is 25 inches long, an inch diameter and weighs half a pound. It is straight with one rounded side and one flatter.

In December 2016, archaeologists from the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment unearthed a new throwing stick in layer 13/11-4. Like all but one of its predecessors, it was made of spruce wood. It is 25 inches long, an inch diameter and weighs half a pound. It is straight with one rounded side and one flatter.

Use-wear analysis conducted by Veerle Rots from the University of Liège shows how the maker of the throwing stick used stone tools to cut the branches flush and then to smooth the surface of the artifact. The artifact preserves impact fractures and damage consistent with that found on ethnographic and experimental examples of throwing sticks.

When in flight, throwing sticks, also referred to as “rabbit sticks” and “killing sticks” rotate around their center of gravity, and do not return to the thrower, as is the case with boomerangs. Instead the rotation helps to maintain a straight, accurate trajectory while increasing the likelihood of striking prey animals. Jordi Serangeli explains: “They are effective weapons at diverse distances and can be used to kill or wound birds or rabbits or to drive larger game, such as the horses that were killed and butchered in large numbers in the Schöningen lakeshore.” Remains of swans and ducks are well-documented in the find horizon.

Experiments show that throwing sticks of this size reach maximum speeds of 30 meters per second. Dr. Gerlinda Bigga, who studies the structure of the wood used for tools, remarked that “Ethnographic studies from North America, Africa and Australia show that the range of such weapons varies from 5 to over 100 meters.”

The find has been published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.