Five of Egypt’s most spectacular heritage sites are open for virtual business with outstanding 3D models. The oldest of the four sites is the tomb of Queen Meresankh III, consort of the 4th Dynasty pharaoh Khafre, builder of the second largest pyramid at Giza. She was her husband’s niece and the granddaughter of Pharaoh Khufu, builder of the largest, the Great Pyramid of Giza. She died shortly after Khafre around 2532 B.C. Her elaborately decorated mastaba tomb, possibly built for her mother who ended up outliving her, is just east of her grandfather’s pyramid.

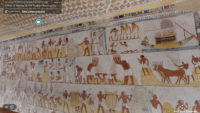

The next in chronological order is the tomb of Menna in the Theban Necropolis. Menna was an 18th Dynasty scribe and overseer of fields owned by the pharaoh and the temple of Amun-Ra. His duties included supervising the small army of scribes who recorded the size of fields and their crop yields and inspected the laborers at work. Menna would then report to the administration of the pharaoh’s granaries. These activities are recorded on wall paintings whose style identifies them as having been created during the reign of Amenhotep III. The tomb is one of the most visited sites on Luxor’s west bank because of how excellently preserved the paintings still are today.

The next in chronological order is the tomb of Menna in the Theban Necropolis. Menna was an 18th Dynasty scribe and overseer of fields owned by the pharaoh and the temple of Amun-Ra. His duties included supervising the small army of scribes who recorded the size of fields and their crop yields and inspected the laborers at work. Menna would then report to the administration of the pharaoh’s granaries. These activities are recorded on wall paintings whose style identifies them as having been created during the reign of Amenhotep III. The tomb is one of the most visited sites on Luxor’s west bank because of how excellently preserved the paintings still are today.

The tomb of Menna underwent an ambitious conservation project from 2007-2009 during which it was precisely documented with high-resolution photography and precisely mapped. The paintings were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence, RAMAN spectrometry and colorimetry to help conservators determine how best to stabilize and repair them.

Still ancient but not quite so ancient is the Red Monastery, a Coptic Orthodox monastery built in the 5th century near the modern city of Sohag on the west bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt. Its main church, dedicated to Saint Pshoi, is built of red brick and has unique architectural features. Its portals and columns were custom-built instead of pilfered from ancient Roman or pharaonic monuments. The triconch sanctuary’s three apses are adorned with richly painted columns. Its walls are decorated top to bottom, with frescoes of saints in niches. It is still an active monastery today and is a site of pilgrimage for Coptic Christians.

Still ancient but not quite so ancient is the Red Monastery, a Coptic Orthodox monastery built in the 5th century near the modern city of Sohag on the west bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt. Its main church, dedicated to Saint Pshoi, is built of red brick and has unique architectural features. Its portals and columns were custom-built instead of pilfered from ancient Roman or pharaonic monuments. The triconch sanctuary’s three apses are adorned with richly painted columns. Its walls are decorated top to bottom, with frescoes of saints in niches. It is still an active monastery today and is a site of pilgrimage for Coptic Christians.

Medieval Egypt is also on the virtual menu. The 14th century Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Barquq is not open to tourists, so the virtual tour is a rare opportunity to view some pretty spectacular architectural features that you couldn’t see in person.

Medieval Egypt is also on the virtual menu. The 14th century Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Barquq is not open to tourists, so the virtual tour is a rare opportunity to view some pretty spectacular architectural features that you couldn’t see in person.

Rounding out the religious heritage of Egypt is Cairo’s Ben Ezra Synagogue. While the current building was completed in 1892, there were predecessor synagogues on the site going back at least to the 9th century, and the Ben Ezra congregation is even older than that, possibly predating Islam. Its  antiquity was confirmed when a massive trove of almost half a million Jewish manuscript fragments were discovered in the synagogue’s geniza (storeroom). This extraordinary collection of documents date from 870 to the 19th century and include both secular and religious writings in several languages. They were removed to Britain in the late 19th century and are now scattered in libraries throughout the UK and the US.

antiquity was confirmed when a massive trove of almost half a million Jewish manuscript fragments were discovered in the synagogue’s geniza (storeroom). This extraordinary collection of documents date from 870 to the 19th century and include both secular and religious writings in several languages. They were removed to Britain in the late 19th century and are now scattered in libraries throughout the UK and the US.

Sadly, there is no Ben Ezra congregation anymore; there are only a handful of Egyptian Jews remaining in Cairo today. The synagogue is a museum now, no longer used for services.