A monumental map of Armenia in the University Library of Bologna has been digitized with gigapixel photo stitching technology that allows viewer to explore the image in ultra-high definition.

A monumental map of Armenia in the University Library of Bologna has been digitized with gigapixel photo stitching technology that allows viewer to explore the image in ultra-high definition.

The Tabula Chorographica Armenica was commissioned by Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, a Bolognese nobleman, diplomat, soldier, world traveler, naturalist, author and all-around polymath whose unquenchable thirst for knowledge drove him to amass an enormous collection of manuscripts that is now at the University of Bologna. (Fun fact: The University of Bologna was founded in 1088 and is the oldest continuously operating university in the world. Its motto, “Alma Mater Studiorum” meaning “nuturing mother of studies,” is the origin of the term “alma mater” for the school you attended.)

Born in 1658, Marsili was privately educated and attended lectures in medicine, mathematics and botany at the renowned university. In 1680, his endless curiosity drove him to join a diplomatic mission to Constantinople where he spent his free time studying the seas. He invented new devices in order to study the coastline, currents, marine animals, water salinity and winds. He published these observations in his first book in 1681.

That same year, he joined the army of the Holy Roman Empire solely for the opportunity it afforded him to travel throughout Eastern Europe. When he was captured by the Ottoman Empire, he was made to distribute coffee to its soldiers besieging Vienna in 1683. So naturally he turned that experience into a treatise on coffee and its supposed medicinal effects.

He was sent to Constantinople again in 1691. His mission was to test the waters (not literally this time) for a peace treaty between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire. He spent a year there. The negotiations went nowhere, but he put his unquiet mind to good use yet again by commissioning a monumental map of the Armenian church.

He was sent to Constantinople again in 1691. His mission was to test the waters (not literally this time) for a peace treaty between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire. He spent a year there. The negotiations went nowhere, but he put his unquiet mind to good use yet again by commissioning a monumental map of the Armenian church.

Armenians had been forced by Shah Abbas I of Persia to move into Persian territory in 1604 and in 1638, Persia and the Ottoman Empire divided Armenia between themselves. The Armenian Patriarchate had been established in Constantinople by express invitation of Sultan Mehmed II in 1461, so by the time of Marsili’s second stay in Constantinople, the city had been the most important center of Armenian religion, scholarship and culture for more than two centuries. Fascinated by the history of the Armenian church, its polemical debates with Roman Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy, Marsili asked Armenian scholar, scribe and illuminator Eremia Çelebi K‘ēōmiwrčean and his son Tēr Małak’ia to map it all out for him.

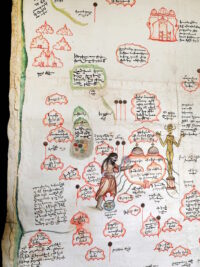

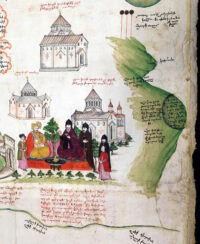

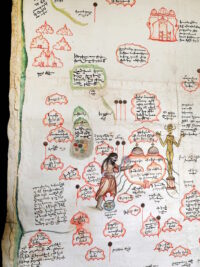

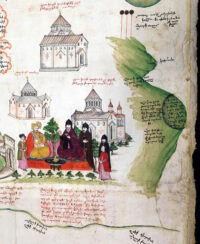

They crafted the large-scale map by gluing 16 sheets of paper to a canvas backing and then drawing hundreds of monasteries, churches and sanctuaries in the four catholicosates (a regional primacy headed by a single leader or catholicos) that existed in the Armenian Apostolic Church at that time. The complete map is 11 feet and nine inches long by three feet 11 inches wide.

They crafted the large-scale map by gluing 16 sheets of paper to a canvas backing and then drawing hundreds of monasteries, churches and sanctuaries in the four catholicosates (a regional primacy headed by a single leader or catholicos) that existed in the Armenian Apostolic Church at that time. The complete map is 11 feet and nine inches long by three feet 11 inches wide.

The most significant churches are accurately drawn and everything is fully captioned. The ink drawings were painted in with watercolors. The four catholicosates are color-coded so it’s clear at a glance which churches belong to which catholicosate. Palm fronds indicate a female hermitage while olive branches indicate a male one. Among the notable illustrations are Saint Gregory the Illuminator banishing a golden idol with a censer, and a meeting between the Catholicos and the Persian governor with the Etchmiadzin Cathedral to their left and Mount Ararat to their right. Annotations include a history of the Armenian church and a recounting of the commissioning and creation of the map.

The great map left Constantinople with Marsili who would continue to be heavily involved in the fighting and diplomacy between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Wherever he went, he parlayed his assignments into new research and treatises. His one big failure — the 1703 surrender of the fortress of Breisach to the French in the War of Spanish Succession — put paid to his career with the HRE and he returned to Bologna where he co-founded the Institute of Sciences that would be closely affiliated with the University. He donated his vast collection of manuscripts to the Institute just before his death in 1730.

The map was just one entry in a very long catalogue and was not published. Its existence only became known to Armenian scholars in the late 18th century, but the lore had some of the details wrong. K‘ēōmiwrčean was said to have created it for the “Ambassador of Austria,” so the map was sought in Vienna among the enormous Hapsburg holdings. Marsili’s name had gotten lost in the game of historical telephone, and nobody thought to check in Bologna for a map commissioned by an ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire.

The map was just one entry in a very long catalogue and was not published. Its existence only became known to Armenian scholars in the late 18th century, but the lore had some of the details wrong. K‘ēōmiwrčean was said to have created it for the “Ambassador of Austria,” so the map was sought in Vienna among the enormous Hapsburg holdings. Marsili’s name had gotten lost in the game of historical telephone, and nobody thought to check in Bologna for a map commissioned by an ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire.

Then again, not even Bologna knew what a treasure it had. It fell off the radar for three hundred years, re-emerging only in 1991 when researchers found it in the University Library while preparing for an exhibition of maps. The digitization project was also engendered by an exhibition, this time of Armenian material in the University Library of Bologna. The gigapixel image will be projected onscreen during the opening of the exhibition on Friday, February 17th. Those of us without reservations for the event can skip ahead and just explore the gigantic masterpiece on our own time.

Explore the full map here. Explore it divided into five sections for ease of navigation here.

A funerary stele from the Roman imperial era with a high-relief portrait of the deceased has been discovered in the hill town of Bucchianico in south central Italy’s Abruzzo region. The stone slab came to light during construction of a roundabout, spotted by the archaeologist supervising the work crew. It does not appear to have been found in its original location. It was likely displaced from the burial it was marking in antiquity or it may have been a secondary burial. Archaeologists will return to excavate the find site thoroughly in the hopes of finding traces of the grave.

A funerary stele from the Roman imperial era with a high-relief portrait of the deceased has been discovered in the hill town of Bucchianico in south central Italy’s Abruzzo region. The stone slab came to light during construction of a roundabout, spotted by the archaeologist supervising the work crew. It does not appear to have been found in its original location. It was likely displaced from the burial it was marking in antiquity or it may have been a secondary burial. Archaeologists will return to excavate the find site thoroughly in the hopes of finding traces of the grave. The Mettii were a prominent plebian family in the early imperial era. Originally from southern Italy a couple of regions down the boot from Abruzzo, the family rose in importance in the late Republic. Marcus Mettius was a legate of Julius Caesar’s in 58 B.C. The first Mettius to attain the rank of consul was appointed by the emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 A.D.) Another three followed, giving the Mettii four consuls on their family track record between the 70s and 128 A.D. The one appointed in 103 A.D. was a Gaius (or Caius), Gaius Trebonius Proculus Mettius Modestus, although of course there’s no way of knowing if he was the former owner of the freedwoman Mettia Rufa as Roman families used the same handful of first names over and over again.

The Mettii were a prominent plebian family in the early imperial era. Originally from southern Italy a couple of regions down the boot from Abruzzo, the family rose in importance in the late Republic. Marcus Mettius was a legate of Julius Caesar’s in 58 B.C. The first Mettius to attain the rank of consul was appointed by the emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 A.D.) Another three followed, giving the Mettii four consuls on their family track record between the 70s and 128 A.D. The one appointed in 103 A.D. was a Gaius (or Caius), Gaius Trebonius Proculus Mettius Modestus, although of course there’s no way of knowing if he was the former owner of the freedwoman Mettia Rufa as Roman families used the same handful of first names over and over again.