The wreck of SS Ventnor, a ship that went down in 1902 carrying the remains of 499 Chinese gold miners from New Zealand back to their homes in China’s Guangdong province, has been found. The ship was discovered 21 kilometers (13 miles) west of Hokianga Harbour under 150 meters (492 feet) of water. The general area of the sinking was known, but it has taken 112 years to find the actual wreck.

The Ventnor Project Group, funded by Definitive Productions which is making a documentary about the shipwreck, first spotted the wreck in December of 2012 using echo sounding sonar. In January of 2013, they enlisted Keith Gordon, former president of the New Zealand Underwater Heritage Group, to investigate the site further. Using a remotely operated underwater vehicle, the team was able to photograph the wreck. The last step was sending divers to record the wreck on video. They confirmed that it was indeed the Ventnor.

In April the divers returned and were able to retrieve artifacts that might aid in identification. They recovered the ship’s bell and a few other pieces (some plates, a porthole window) which have been cleaned and conserved, but nothing with a name that would clinch the deal. Authorities in China and New Zealand were notified of the discovery and the shipwreck was gazetted by New Zealand Heritage, which means no objects can be removed the site without permission. No coffins or human remains have been found yet. The Ventnor Project Group needs to raise another 400,000 New Zealand dollars to dive the wreck site more extensively. Meanwhile, the Royal New Zealand Navy is going forward with separate plans they made before the announcement of the find to search for the wreck next month.

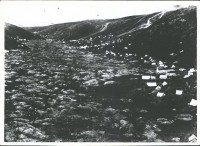

The tragedy of the Ventnor is a window into the Chinese experience in New Zealand. The first Chinese immigrants were invited to New Zealand by the Otago Provincial Council who needed people willing to do backbreaking labour in the gold mines of Otago on the South Island. Gold had been found in Gabriel’s Gully in 1861, setting off the Otago gold rush. Five years later, the gold fields had been thoroughly picked over and the work of extracting gold, never easy, got so hard miners left for greener pastures. The population of European miners plummeted from 19,000 men in early 1864 to 6,000 in late 1865. That’s when they sent the call out to Guangdong province for miners to rework the area. Guangdong was suffering in the aftermath of the suppressed Taiping Rebellion, so thousands of men made their way to New Zealand in hope of making a decent living.

By 1869, there were more than 2,000 Chinese, most of them from the Guangzhou area, in New Zealand. By 1881, there were more than 5,000. That same year, the New Zealand government passed its version of the U.S. Exclusion Act, a poll tax that charged every Chinese immigrant £10 to enter the country, and only allowed one Chinese immigrant for every 10 tons of cargo. In 1896 those numbers got a lot worse: the per head tax was raised to £100 and only one Chinese immigrant was allowed per 200 tons of cargo. The poll tax remained in force until 1934 when the Japanese invaded Manchuria.

By 1869, there were more than 2,000 Chinese, most of them from the Guangzhou area, in New Zealand. By 1881, there were more than 5,000. That same year, the New Zealand government passed its version of the U.S. Exclusion Act, a poll tax that charged every Chinese immigrant £10 to enter the country, and only allowed one Chinese immigrant for every 10 tons of cargo. In 1896 those numbers got a lot worse: the per head tax was raised to £100 and only one Chinese immigrant was allowed per 200 tons of cargo. The poll tax remained in force until 1934 when the Japanese invaded Manchuria.

Amid the simmering racial tensions and the regulatory aggression, the Chinese miners banded together to maintain their customs and support each other. In 1882, a year after the poll tax was enacted, men from Poon Yu and Fah Yuen counties of Guangdong Province founded the Cheong Sing Tong, a subscription association that allowed members to pool their resources so they could send the remains of the dead back to their hometowns in China. According to Chinese tradition, the dead must be buried in the ground of their homes so their descendants can properly tend to them to ensure a good afterlife for the deceased and good fortune for their survivors.

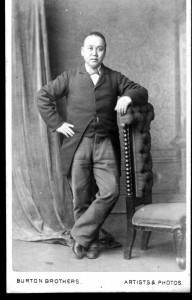

The leader of the Cheong Sing Tong was Choie Sew Hoy, a successful merchant who had arrived with the first wave of immigrants from Poon Yu. Just like in the American gold rushes, the most successful people were those who sold stuff to the miners rather than the guys panning in rivers. Choie Sew Hoy started off with a general store and eventually ran a dozen mining ventures of his own. He was a prominent community leader in Dunedin and well respected by Chinese and European alike.

The leader of the Cheong Sing Tong was Choie Sew Hoy, a successful merchant who had arrived with the first wave of immigrants from Poon Yu. Just like in the American gold rushes, the most successful people were those who sold stuff to the miners rather than the guys panning in rivers. Choie Sew Hoy started off with a general store and eventually ran a dozen mining ventures of his own. He was a prominent community leader in Dunedin and well respected by Chinese and European alike.

In 1883, Hoy and the Cheong Sing Tong exhumed 230 bodies and successfully sent them back to China for reburial. In 1901, they began arrangements for a second shipment. From early 1901 to the September 1902, bodies of Chinese immigrants were exhumed from more than 40 cemeteries, most of them in the Otago area but also from elsewhere in the country. The remains were sent to Choie Sew Hoy’s farm where the bodies were placed in coffins and the bones were individually washed and each bone counted. The small bones were each wrapped in calico. The large bones placed in calico bag to which the small bones were added along with the name of the deceased. The bag was tied and put inside a coffin which was stored in a shed until all coffins were ready to be shipped.

While this process was taking place, Choie Sew Hoy died suddenly in July of 1901 at the age of 64. His son Choie Kum Poy took over the project and Choie Sew Hoy’s body was added to the others for return to China. The ship they chartered to carry this cargo was the SS Ventnor. The Glasgow-built cargo ship was only a year old in October of 1902 when the coffins were loaded and it left Wellington headed for Hong Kong. Along with the crew, there were nine or six (accounts vary) elderly Chinese men on board who were given free passage by the Cheong Sing Tong in exchange for looking after the coffins.

One day after leaving Wellington, the ship, which was apparently traveling too close to the shore, hit rocks near the coast of Taranaki. The captain decided the damage wasn’t so bad they should make for the nearby port of New Plymouth, and there was little point in turning back around to Wellington since they could go almost the same distance north to Auckland and be going in the right direction. His judgment was flawed. The Ventnor took on water and sank off the Hokianga Heads on October 29th, 1902, two days after setting sail. Four lifeboats were launched holding the crew and passengers. Three of them made it to safety. The one holding the captain, among others, did not. Thirteen people died.

One day after leaving Wellington, the ship, which was apparently traveling too close to the shore, hit rocks near the coast of Taranaki. The captain decided the damage wasn’t so bad they should make for the nearby port of New Plymouth, and there was little point in turning back around to Wellington since they could go almost the same distance north to Auckland and be going in the right direction. His judgment was flawed. The Ventnor took on water and sank off the Hokianga Heads on October 29th, 1902, two days after setting sail. Four lifeboats were launched holding the crew and passengers. Three of them made it to safety. The one holding the captain, among others, did not. Thirteen people died.

The tragic fate of the Ventnor was big news at the time, spurring a magisterial inquiry into the cause of the sinking. The official finding, announced on November 21st, 1902, was that the striking of the rocks off Cape Egmont was due either to negligence or incompetence on the part of the captain. Drunkenness, while possible, could not be proven. No blame was assigned to the decision to keep going towards Auckland instead of turning back to Wellington.

The Cheong Sing Tong chartered the Auckland steamer Energy to search for the Ventnor and any of the remains, but most of the coffins, including that of Choie Sew Hoy, were lead-lined and ensconced in the hold. Some plain wooden coffins that were stored on the deck floated and washed ashore. Maori tribespeople from the Te Roroa and Te Rarawa tribes buried the remains with care. They too share the belief that the remains of their people must be buried in the soil of their home, an issue that has been at the forefront of requests for repatriation of Maori remains in anthropological collections around the world.

The disaster of the Ventnor led to the disbanding of the Cheong Sing Tong and the end of the practice of sending coffins back to China in bulk. Remains were still sent home, but on an individual basis. The ship’s manifest was lost with the ship, so we don’t even have a list of names of the 499. Only Choie Sew Hoy is known. Recovering remains from the wreck would be extremely meaningful to the descendants of the miners in New Zealand and China.

The documentary The Lost Voyage of the 499 aired on Maori TV just Monday before the news of the discovery was announced. It’s a moving look at the history of the Ventnor as seen through the eyes of Choie Sew Hoy’s living descendants who travel to the Maori burial sites and to Hoy’s home village to see the first home he built in the 1860s and to pay their respects at his proxy grave.

Thanks for a great discussion on the Chinese gold rush experiences in New Zealand. I studied Chinese American history in college, but never the New Zealand one. It’s interesting to read about it here on this blog. It’s why I keep coming back to know more about history.

A few more interesting facts for readers who read this far:

1. San Francisco is nicknamed “Old Gold Mountain.” It’s named this way after the discovery of the New Gold Mountain in New Zealand. In US and most Chinese communities/cultures, San Francisco is still called “Old Gold Mountain.” What I didn’t realize is that gold was discovered about the same time in US and New Zealand.

2. Chinese benevolent associations or “tongs” are still present in American Chinatowns (most notably in New York City and San Francisco). They’re prominent part of the old Chinatowns and have their own buildings. However, today few new Chinese immigrants are part of these associations, preferring their own family/social networks.

I didn’t know about the OId Gold Mountain nickname or its antecedents in New Zealand. Thank you for the interesting tips. Sadly I did not study Chinese American history in college, but I have developed a great fascination with it since then. Have you been to the Museum of Chinese in America in New York City, by any chance? It’s on my short list of places to see the next time I’m in NYC. Someday I also want to make a pilgrimage to the Kam Wah Chung & Co museum in Oregon. That is the Chinese gold rush experience frozen in time right there.

thanks for the response. No, I haven’t been to the oregon and nyc museums. i live close enough to nyc, so i have no excuse not to go. i know some friends of mine who have visited and enjoyed the experience. i didn’t know about the oregon museum. thanks for the tip. one great book i think anyone interested in the chinese american experiences would enjoy a great book, called Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans, by Ronald Takaki. It was the book we used in college. everyone i met who read the book all agreed it was a great book.