An excavation of the Colosseum’s sewer systems has revealed the ancient Roman versions of Cracker Jacks and ballpark franks and it’s melon and mutton. The study aims to learn more about how the ancient sewer and hydraulic systems operated under the Flavian Amphitheater with a particular focus on solving the mystery of how the underground was flooded during water spectacles. In January 2021, wire-guided robots were sent to video record and laser scan the drains and sewers under the arena. A year later, a stratigraphic excavation of the south collector of the sewer network began, clearing 230 feet of muck that contained archaeological treasure in the form of ancient garbage.

An excavation of the Colosseum’s sewer systems has revealed the ancient Roman versions of Cracker Jacks and ballpark franks and it’s melon and mutton. The study aims to learn more about how the ancient sewer and hydraulic systems operated under the Flavian Amphitheater with a particular focus on solving the mystery of how the underground was flooded during water spectacles. In January 2021, wire-guided robots were sent to video record and laser scan the drains and sewers under the arena. A year later, a stratigraphic excavation of the south collector of the sewer network began, clearing 230 feet of muck that contained archaeological treasure in the form of ancient garbage.

Sewers are often constipated with archaeological material from the very bowels of daily life in the ancient city, and the sewers under the Colosseum contain a unique variety of organic remains left by both the spectacles and the spectators. The excavation of the south collector brought in a rich harvest: the discarded remains of chestnuts, walnuts, pine nuts, hazelnuts, figs, peach pits, plum pits, cherry pits, olive pits, blackberries, elderberries, melon seeds and grape seeds, evidence of the snacks consumed by the audience in the bleachers during the games. They didn’t just have snacks in the stands. It seems spectators rigged up braziers so they could grill up some meat, mostly pork and mutton, as they watched people and animals being butchered for sport.

Sewers are often constipated with archaeological material from the very bowels of daily life in the ancient city, and the sewers under the Colosseum contain a unique variety of organic remains left by both the spectacles and the spectators. The excavation of the south collector brought in a rich harvest: the discarded remains of chestnuts, walnuts, pine nuts, hazelnuts, figs, peach pits, plum pits, cherry pits, olive pits, blackberries, elderberries, melon seeds and grape seeds, evidence of the snacks consumed by the audience in the bleachers during the games. They didn’t just have snacks in the stands. It seems spectators rigged up braziers so they could grill up some meat, mostly pork and mutton, as they watched people and animals being butchered for sport.

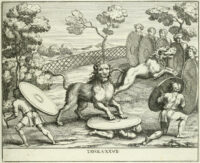

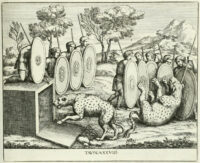

Remains of animals who starred in the games were found as well. There were bones of bears of different sizes, possibly used in acrobatic displays, lions, leopards, ostriches and deer, likely used in the venationes (staged animal hunts). There were also dogs of different sizes. The smallest was less than a foot in height, but stocky and strong, a predecessor of the dachshund. Remains of plants that grew in the Colosseum showed a wide degree of biodiversity, ranging from blackberries to boxwoods and laurels. Some of the plants were spontaneous growth (the international animal and human feces spread led to hundreds if not thousands of different non-native plants taking root in the Colosseum); the evergreens were probably deliberately planted for landscaping.

Remains of animals who starred in the games were found as well. There were bones of bears of different sizes, possibly used in acrobatic displays, lions, leopards, ostriches and deer, likely used in the venationes (staged animal hunts). There were also dogs of different sizes. The smallest was less than a foot in height, but stocky and strong, a predecessor of the dachshund. Remains of plants that grew in the Colosseum showed a wide degree of biodiversity, ranging from blackberries to boxwoods and laurels. Some of the plants were spontaneous growth (the international animal and human feces spread led to hundreds if not thousands of different non-native plants taking root in the Colosseum); the evergreens were probably deliberately planted for landscaping.

The excavation also recovered artifacts. As you would find under the sewer grates of the sports arena today, there’s a lot of spare change down there. Archaeologists unearthed 53 bronze coins from the Late Imperial era, and a rare orichalcum sestertius struck in 170-171 A.D. to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the ascension of Marcus Aurelius to the imperial throne. Personal objects found include bone game dice, a bone pin and clothing elements (shoe nails, leather, studs).

The excavation also recovered artifacts. As you would find under the sewer grates of the sports arena today, there’s a lot of spare change down there. Archaeologists unearthed 53 bronze coins from the Late Imperial era, and a rare orichalcum sestertius struck in 170-171 A.D. to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the ascension of Marcus Aurelius to the imperial throne. Personal objects found include bone game dice, a bone pin and clothing elements (shoe nails, leather, studs).

I can’t embed this video from the Facebook page of the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum, but do yourself a favor and follow the link because it shows urban spelunkers from the organization Roma Sotterranea (Underground Rome) exploring the sewer, squeezing through uncomfortably tight, mucky spaces and pointing out the brick stamps inscribed with the names of the makers which identify the period when that stretch of construction or repairs was done.