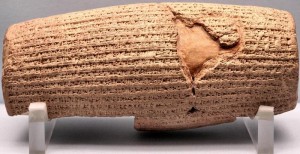

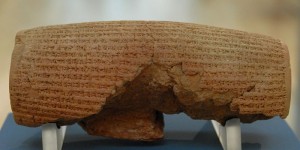

After much controversy and delay, a clay cylinder from the 6th century B.C. celebrating King Cyrus II the Great of Persia’s conquest of Babylon in cuneiform script has arrived in Iran to be displayed in the National Museum for the next 4 months.

The Cyrus Cylinder was discovered by a British Museum archaeologist in the ruins of Babylon in 1879 and has been on display at the museum ever since. It has only traveled twice, in 2006 to Spain, and one notable 2-week visit to Iran in 1971, where it was the centerpiece of Shah Reza Pahlavi’s celebration of 2,500 years of Persian monarchy.

The Shah was very keen to pain his regime as an unbroken continuation of that of Cryus the Great, and he promoted the Cylinder as the original declaration of human rights. In a 1967 book about the White Revolution (his 1963 program of reforms) he said: “the history of our empire began with the famous declaration of Cyrus, which, for its advocacy of humane principles, justice and liberty, must be considered one of the most remarkable documents in the history of mankind.”

The problem is there actually isn’t anything in the Cylinder text about human rights. The inscription details Cyrus’ royal genealogy and sings his praises for restoring local gods to their hometowns, freeing forced laborers (the Book of Ezra says this included the Jews who had been captured by Nebuchadnezzar 50 years earlier), rebuilding Babylon and just generally being so way more awesome than Nabonidus, the Babylonian low-born usurper he defeated at the personal behest of the god Marduk. It’s a classic piece of Mesopotamian style propaganda: praise the new guy and bury it in the foundations of the temple of Marduk. Nabonidus had done the same thing using similar language when he took over, as had his predecessors for a couple of thousand years.

Shah Pahlavi’s use of it to legitimize his own rule was quite congruent with its original intent, and in some ways it worked. The “first declaration of human rights” label stuck, for instance, and you’ll see it all over the articles today about the arrival of the Cylinder in Tehran. In 1971, there was a furor in the press at the time demanding the “return” of the Cylinder to Iran, despite the fact that it was found in what is now Iraq, is all about Babylon and was legally exported.

After the British Museum got it back — not without some difficulty — the board decided it would be unwise to lend it to Iran again. That’s where things stood until 2005, when the British Museum put on a major exhibition about the Persian Empire in collaboration with the Iranian government. Iran loaned the museum several important artifacts under a reciprocal agreement that the Cyrus Cylinder would be loaned back to them.

In early 2009, the British Museum announced the Cylinder would be loaned to Iran for 3 months later in the year. After the June protests and violence in the wake of the disputed reelection of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the museum backtracked. They decided it would be safer to delay the loan.

Iran was less than pleased. The government threatened to cut off all ties with the museum unless they got the as-promised loan within 2 months. Another display date was set (January 2010) and that deadline too passed, this time ostensibly because the British Museum found some other fragments with the same text and wanted to compare them to the Cylinder. They rescheduled the loan for July, but Iran was not mollified.

In February, Iran announced it was making good on its threat and cutting off ties with the museum. In April, the National Museum of Iran demanded the British Museum replay them for the $300,000 cost of a special display case built to show the Cyrus Cylinder. That was the last I’d heard of the controversy until today when articles popped up all over the place announcing the arrival of the Cylinder in Tehran.

The British Museum sent a delegation of experts/babysitters along with it, probably to ensure they actually get it back.