The Welsh government has taken a most beautiful payment in kind for an outstanding inheritance tax bill: an elaborately decorated 2000-year-old Celtic iron fire guard known as the Capel Garmon Firedog. The owners of the firedog had previously lent it to the Amgueddfa Cymru – the National Museum of Wales, who generously sent me the high resolution pictures included in this post that I couldn’t find anywhere else — where it was one of the most important artifacts in its exhibit of early Celtic art.

The Welsh government has taken a most beautiful payment in kind for an outstanding inheritance tax bill: an elaborately decorated 2000-year-old Celtic iron fire guard known as the Capel Garmon Firedog. The owners of the firedog had previously lent it to the Amgueddfa Cymru – the National Museum of Wales, who generously sent me the high resolution pictures included in this post that I couldn’t find anywhere else — where it was one of the most important artifacts in its exhibit of early Celtic art.

The Acceptance in Lieu (AIL) scheme allows owners to transfer “pre-eminent” heritage objects (works of art, archives, manuscripts) to public ownership as full or partial payment of their inheritance taxes. The Minister for Housing, Regeneration and Heritage approves the artifacts on the advice of independent experts and allocates them to a public museum.

The firedog was discovered in 1852 by a man digging a ditch in a peat field near the village Capel Garmon in county Conwy, north Wales. It appeared to have been buried deliberately, probably as an offering to the gods, as it was found intact deep in the peat, lying on its side with large stones placed at each end. This is in keeping with the well-established tradition of burying metal objects in lakes, rivers and bogs as a religious devotion in Iron Age Wales.

The firedog was discovered in 1852 by a man digging a ditch in a peat field near the village Capel Garmon in county Conwy, north Wales. It appeared to have been buried deliberately, probably as an offering to the gods, as it was found intact deep in the peat, lying on its side with large stones placed at each end. This is in keeping with the well-established tradition of burying metal objects in lakes, rivers and bogs as a religious devotion in Iron Age Wales.

It certainly was not a commonplace object when it was first crafted between 50 B.C. and 50 A.D. (The date is an estimate based on comparisons with other firedogs found at chieftain burials. There was no archaeological excavation following its discovery in 1852, so we have no access to the original context where stratigraphic analysis or radiocarbon dating of nearby organic elements could give us a specific burial date.) It would originally have been one of a pair, used to hold logs or skewers on the central hearth of a chieftain’s round-house, an emblem of the chieftain’s wealth and power.

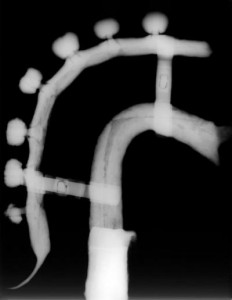

As part of an experiment to duplicate the firedog, conservators X-rayed it and found that it was made of 85 pieces shaped separately and then put together. Archaeologists estimate that the initial weight of iron used to make the twin firedogs was a staggering 38 kilos (84 pounds). The single firedog today is approximately 42 inches long, 30 inches high and weighs nine kilos (20 pounds).

As part of an experiment to duplicate the firedog, conservators X-rayed it and found that it was made of 85 pieces shaped separately and then put together. Archaeologists estimate that the initial weight of iron used to make the twin firedogs was a staggering 38 kilos (84 pounds). The single firedog today is approximately 42 inches long, 30 inches high and weighs nine kilos (20 pounds).

Iron was hard to come by and very valuable. To use this much of it for a decorative (albeit practical) item must have been a prohibitively expensive proposition. The craft itself represents an enormous investment of time. Experts think it would have taken Iron Age blacksmiths perhaps as long as three years to create the firedogs, from gathering the ore, to smelting it through to crafting all the individual parts and then putting them together.

It’s no wonder the Minister approved this trade. For now, the Capel Garmon Firedog will remain on display in the Early Wales gallery of the National Museum in Cardiff. It will eventually be moved to new galleries currently still in the planning phase at St Fagans: National History Museum, another of seven national museums under the aegis of Amgueddfa Cymru.