Scientists from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California together with digital conversion experts at the Library of Congress and curators of the work and industry division of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History have succeeded in playing some of the earliest experimental sound recordings by Alexander Graham Bell. Bell, his cousin Chicester Bell and their colleague Charles Sumner Tainter created a business called Volta Laboratory Associates dedicated to research and development of sound recording technology. Between 1881 and 1885, they studied and experimented with a number of recording technologies at their lab in Washington, D.C., recording sound on metal, rubber, glass and beeswax, among other media.

Scientists from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California together with digital conversion experts at the Library of Congress and curators of the work and industry division of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History have succeeded in playing some of the earliest experimental sound recordings by Alexander Graham Bell. Bell, his cousin Chicester Bell and their colleague Charles Sumner Tainter created a business called Volta Laboratory Associates dedicated to research and development of sound recording technology. Between 1881 and 1885, they studied and experimented with a number of recording technologies at their lab in Washington, D.C., recording sound on metal, rubber, glass and beeswax, among other media.

It was a heady time for inventors, with the likes of Bell, Thomas Edison and Emile Berliner all competing to unlock the key to playable sound recordings. To ensure they had evidence to support any contested patent application, the inventors stored recordings and research notes with the Smithsonian. The National Museum of American History thus has been the proud owner of 400 of the earliest audio recordings ever made since the late 19th century. None of them were playable, however, so it was a collection of 400 silent audio recordings.

When Carlene Stephens, the curator in charge of the collection, read an article (which I blogged about at the time, oh yeah) about how the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory had found a way to read the sound off an 1860 recording that was basically squiggles on paper, visions of 400 previously untastable sugar plums danced in her head. She set up a collaborative pilot program that would attempt to read six of Bell’s recordings use the new technology.

When Carlene Stephens, the curator in charge of the collection, read an article (which I blogged about at the time, oh yeah) about how the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory had found a way to read the sound off an 1860 recording that was basically squiggles on paper, visions of 400 previously untastable sugar plums danced in her head. She set up a collaborative pilot program that would attempt to read six of Bell’s recordings use the new technology.

Advances in computer technology made it possible to play back the recordings, said Carl Haber, a senior scientist at the Berkeley Lab. He noted that 10 years ago specialists would have struggled with computer speeds and storage issues. The digital images that now can be processed into sound within minutes would have taken days to process a decade ago.

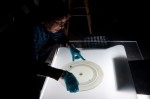

Many of the recordings are fragile, and until recently it had not been possible to listen to them without damaging the discs or cylinders.

So far, the sounds of six discs have been successfully recovered through the process, which creates a high-resolution digital map of the disc or cylinder. The map is processed to remove scratches and skips, and software reproduces the audio content to create a standard digital sound file.

For more technical details, pictures of the discs and most importantly, all six converted recordings, see the program’s website here. They’re very short audio tests, basically, like the first few verses of Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” soliloquy, random trills and countdowns. My favorite by far is the second “Mary Had a Little Lamb” recording which is interrupted by an “Oh no!” at the end. It’s the first recorded mistake! (That we’ve heard, anyway.)

[audioplayer file=”http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Mary-had-a-little-lamb.mp3″ titles=”Mary Had a Little Lamb”]

We don’t know who the speakers are right now. They could be either Bell cousin, Tainter or someone else entirely. Researchers are hoping as they convert more and more of the Volta recordings they’ll be able to identify the voices. The pilot was funded by a $600,000 grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Sciences. The Smithsonian is working to secure more funding so they can make their whole audio archive speak for the first time.

The mystery coin is inscribed “AIRDECONUT” on one side, and has the words DNS (for Dominus) and REX in the shape of the cross on the other. Experts believe “Airdeconut” is an Anglo-Saxon attempt to spell the Viking name Harthacnut, and the Dominus Rex indicate that Airdeconut was a Christian ruler. The style of the coin is similar to coins from the Viking kings of Northumbria around 900 A.D., but unlike those kings, Airdeconut/Harthacnut hasn’t appeared on the historical record before now.

The mystery coin is inscribed “AIRDECONUT” on one side, and has the words DNS (for Dominus) and REX in the shape of the cross on the other. Experts believe “Airdeconut” is an Anglo-Saxon attempt to spell the Viking name Harthacnut, and the Dominus Rex indicate that Airdeconut was a Christian ruler. The style of the coin is similar to coins from the Viking kings of Northumbria around 900 A.D., but unlike those kings, Airdeconut/Harthacnut hasn’t appeared on the historical record before now.