After years of planning, pilot programs and painstaking effort by scholars, conservators and NASA scientists, the first five Dead Sea Scrolls have gone online. Four of them are part of the original seven scrolls discovered by a Bedouin shepherd in a cave at Qumran, just above the Dead Sea, in 1947. One of them, the Temple Scroll, was discovered in a cave less than a mile away in 1956.

The Great Isaiah Scroll, the Temple Scroll, the War Scroll, the Community Rule Scroll and the Commentary on the Habakkuk Scroll, five of the most complete and important scrolls discovered in caves on the banks of the Dead Sea, are kept in a highly secured vault by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The isolation is necessary to protect the 2,000-year-old documents from any further deterioration, but it also means anyone who would like to peruse these invaluable Biblical manuscripts would have to jump through nearly impossible hoops.

The Great Isaiah Scroll, the Temple Scroll, the War Scroll, the Community Rule Scroll and the Commentary on the Habakkuk Scroll, five of the most complete and important scrolls discovered in caves on the banks of the Dead Sea, are kept in a highly secured vault by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The isolation is necessary to protect the 2,000-year-old documents from any further deterioration, but it also means anyone who would like to peruse these invaluable Biblical manuscripts would have to jump through nearly impossible hoops.

Not any more. Photographer Ardon Bar-Hama has taken high resolution pictures up to 1,200 megapixels and Google technology has created a database that allows anyone with an Internet connection to get so close to the scrolls that you can see the most minute details of ink and parchment. Each scroll is introduced with more about its contents and history, both written and in short explanatory videos. The Dead Sea Scrolls Online site lets users click on the Hebrew text to get an English translation, and you can join the site via Google Connect to suggest translations in other languages or just to leave comments. The scrolls are all searchable, not just locally on the site but also via Google web search.

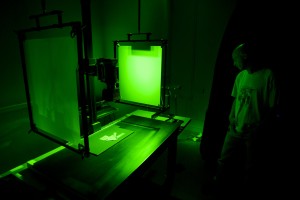

Google’s involvement with the Dead Sea Scrolls doesn’t end there. They are also collaborating with the Israel Antiquities Authority on a separate digitization project that will put the IAA’s collection of approximately 30,000 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments totaling 900 manuscripts on the Internet. This project will go several steps beyond high resolution photography.

Google’s involvement with the Dead Sea Scrolls doesn’t end there. They are also collaborating with the Israel Antiquities Authority on a separate digitization project that will put the IAA’s collection of approximately 30,000 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments totaling 900 manuscripts on the Internet. This project will go several steps beyond high resolution photography.

The MegaVision system will enable the digital imaging of every Scroll fragment in various wavelengths in the highest resolution possible and allow long term monitoring for preservation purposes in a non-invasive and precise manner. The images will be equal in quality to the actual physical viewing of the Scrolls, thus eliminating the need for re-exposure of the Scrolls and allowing their preservation for future generations. The technology will also help rediscover writing and letters that have “vanished” over the years; with the help of infra-red light and wavelengths beyond, these writings will be brought “back to life”, facilitating new possibilities in Dead Sea Scrolls research.

This project is scheduled to be complete by 2016. By then, the Israel Museum’s digitization should also be complete, so if all goes well, the entirety of the Dead Sea Scrolls will be online and available to us all within five years.