The international team of archaeologists led by the University of Southampton and the British School at Rome excavating the ancient Roman harbor town of Portus have discovered the remains of a massive building they think may have been an Imperial shipyard used to build some of Rome’s largest ships.

The international team of archaeologists led by the University of Southampton and the British School at Rome excavating the ancient Roman harbor town of Portus have discovered the remains of a massive building they think may have been an Imperial shipyard used to build some of Rome’s largest ships.

Few Roman shipyards have been found, and none for the city of Rome itself. Two small possibilities — one in the city on the Tiber near the Monte Testaccio (an artificial hill the Romans made from broken olive oil amphorae unloaded from merchant ships), the other at Ostia — have been advanced, but they would not have been large enough to service all of Imperial Rome’s ship building needs.

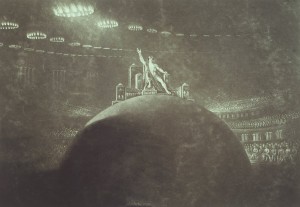

Five stories high and with direct access to both the Claudian and hexagonal Trajanic basins of Portus, this shipyard is on a whole other scale.

Five stories high and with direct access to both the Claudian and hexagonal Trajanic basins of Portus, this shipyard is on a whole other scale.

The huge building the team has discovered dates from the 2nd century AD and would have stood c. 145 metres [475 feet] long and 60 metres [196 feet] wide – an area larger than a football pitch [soccer field]. In places, its roof was up to 15 metres [50 feet] high, or more than three times the height of a double-decker bus. Large brick-faced concrete piers or pillars, some three metres wide and still visible in part, supported at least eight parallel bays with wooden roofs.

“This was a vast structure which could easily have housed wood, canvas and other supplies and certainly would have been large enough to build or shelter ships in. The scale, position and unique nature of the building lead us to believe it played a key role in shipbuilding activities,” comments Southampton’s Professor Keay, who also leads the archaeological activity of the BSR.

They’ve found a wide vaulted area that formed the western wall of the complex and the western-most bay. Estimates based on this one bay suggest they were 12 meters (40 feet) wide and 58 meters (190 feet) long. The piers on the northern end facing the Claudian basin were 6 x 5 feet, while the ones on the southern end on the Trajanic basin were larger at 10 x 5.5 feet, so archaeologists think that the primary entrance point was a massive arch on southern side, with a smaller but still notable entrance on the north.

They’ve found a wide vaulted area that formed the western wall of the complex and the western-most bay. Estimates based on this one bay suggest they were 12 meters (40 feet) wide and 58 meters (190 feet) long. The piers on the northern end facing the Claudian basin were 6 x 5 feet, while the ones on the southern end on the Trajanic basin were larger at 10 x 5.5 feet, so archaeologists think that the primary entrance point was a massive arch on southern side, with a smaller but still notable entrance on the north.

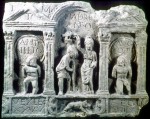

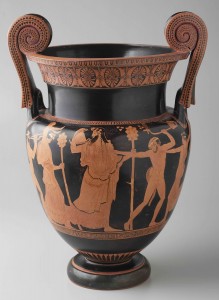

Epigraphic evidence supports the existence of a major shipyard in Portus. Inscriptions found at the site mention that the guild of shipbuilders (the corpus fabrum navalium portensium) had a presence in the port. There’s artistic evidence that Roman’s had shipyards like this. A mosaic found in a villa just outside the ancient city of Rome shows the facade of a large building with a ship nestled in each arched bay.

One key piece of evidence still missing is the remains of any of the ramps that would have been necessary to launch newly built ships from dry dock into the harbor. Professor Keay thinks they may be hidden beneath the concrete embankment built in the early 20th century. Getting under there would be challenging, to say the least, and there’s no reason to believe any of them have survived.