On May 19th, 1902, an explosion in the coal mine at Fraterville in Tennessee’s Coal Creek Valley claimed the lives of 216 men and boys. Only 184 of them were ever identified. It is the worst mining disaster in Tennessee history and one of the top five worst in the nation’s history.

On May 19th, 1902, an explosion in the coal mine at Fraterville in Tennessee’s Coal Creek Valley claimed the lives of 216 men and boys. Only 184 of them were ever identified. It is the worst mining disaster in Tennessee history and one of the top five worst in the nation’s history.

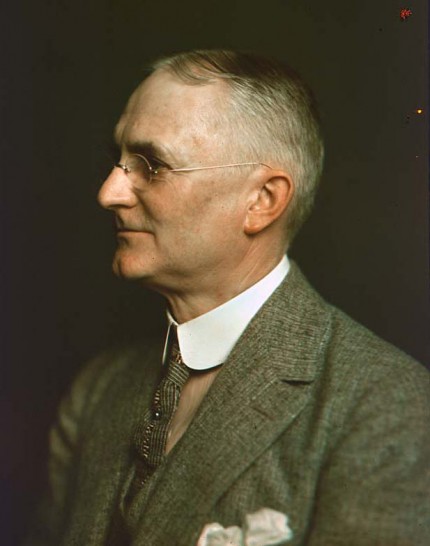

Before that fateful day, the Fraterville Mine had been operating without incident for over 30 years. Its owner, former Union Major Eldad Cicero Camp, had been a U.S. District Attorney for Eastern Tennessee and was widely respected as someone who treated his employees fairly and ran as safe a shop as possible considering the inherent dangers of the job.

Major Camp was one of the only industrialists who refused to utilize the state’s appalling convict leasing system, a post-Civil War pretext for Southern states to re-enslave African-Americans using the 13th Amendment which outlawed involuntary servitude except as punishment for crime. When the war was over, black men became targets of law enforcement, arrested for petty/fictional crimes so that they could be leased to private industry for a small fee and the cost of their upkeep. The latter was insignificant because the leased convicts were often starved to death when they weren’t beaten or worked to death, and the former was far cheaper than free workers.

Major Camp was one of the only industrialists who refused to utilize the state’s appalling convict leasing system, a post-Civil War pretext for Southern states to re-enslave African-Americans using the 13th Amendment which outlawed involuntary servitude except as punishment for crime. When the war was over, black men became targets of law enforcement, arrested for petty/fictional crimes so that they could be leased to private industry for a small fee and the cost of their upkeep. The latter was insignificant because the leased convicts were often starved to death when they weren’t beaten or worked to death, and the former was far cheaper than free workers.

Instead, Camp hired expert miners, most of them Welsh immigrants, and paid them in cash per tonnage, not company scrip, and never scammed them with credit schemes and company stores. Fraterville miners were members of the United Mine Workers of America within years of its creation in 1890. Excited by the opportunity to make real money and own their own homes, the miners often encouraged their family members to join them.

Camp’s son George had learned the mining trade by going down the shafts himself, so he knew the miners and the work intimately. He had been promoted to supervisor by the time of the explosion but was very much hands-on. Had he not returned home to get a coat because it started raining, he would have been in the mine when the explosion occurred.

According to the Commissioner of Labor report, at 7:20 AM, no more than an hour after the miners had begun their work day, a thick billow of black smoke and particulate matter poured out of the mine entrance and ventilation shaft. Although the mine was reputed to be generally free of methane, some may have leaked from an abandoned, unventilated nearby mine which the Fraterville miners had recently tunneled into. (Perhaps not coincidentally, that mine had been worked by leased convicts.) Another possibility suggested at the time was that the Fraterville mine’s ventilation system had been negligently shut down over the weekend by the ventilation furnace operator, Tipton Hightower, allowing toxic gases to build up in the shafts. (George Camp vouched for his diligence and Hightower was later tried and acquitted of this charge.)

According to the Commissioner of Labor report, at 7:20 AM, no more than an hour after the miners had begun their work day, a thick billow of black smoke and particulate matter poured out of the mine entrance and ventilation shaft. Although the mine was reputed to be generally free of methane, some may have leaked from an abandoned, unventilated nearby mine which the Fraterville miners had recently tunneled into. (Perhaps not coincidentally, that mine had been worked by leased convicts.) Another possibility suggested at the time was that the Fraterville mine’s ventilation system had been negligently shut down over the weekend by the ventilation furnace operator, Tipton Hightower, allowing toxic gases to build up in the shafts. (George Camp vouched for his diligence and Hightower was later tried and acquitted of this charge.)

Whatever the source of the gas, the miners’ oil wick lamps — open flames hooked into their hats — ignited it causing a massive explosion. That in turn ignited the coal dust, spreading the fire throughout the mine. George Camp organized a rescue party. They tried to go down the main shaft to find any survivors, but they only made it 200 feet when the afterdamp, a toxic mixture of gases produced by the explosion, forced them to turn back. It wasn’t until 4:00 that the rescue party was able to jury-rig a venting system and reach the main site of the explosion.

Whatever the source of the gas, the miners’ oil wick lamps — open flames hooked into their hats — ignited it causing a massive explosion. That in turn ignited the coal dust, spreading the fire throughout the mine. George Camp organized a rescue party. They tried to go down the main shaft to find any survivors, but they only made it 200 feet when the afterdamp, a toxic mixture of gases produced by the explosion, forced them to turn back. It wasn’t until 4:00 that the rescue party was able to jury-rig a venting system and reach the main site of the explosion.

They found total devastation.

Brattices [(wood partitions erected in mines to help ventilate the shafts)] had been destroyed, and along the main entry the force of the explosion was terrific, [sic] timbers and cogs placed to hold a squeeze were blown out, mine cars, wheels, and doors were shattered, and bodies were dismembered. In other parts of the mine no heat or violence was shown, and suffocation had brought death to those whose bodies were found there.

Twenty-six miners survived the blast and immediate choking aftermath. They barricaded themselves in a side passage where the afterdamp and lack of oxygen slowly suffocated them to death. Some of them lived for at least seven hours. We know this because Jacob Vowell, Powell Harmon, John Hendren, Harry Beech, Scott Chapman, James Brooks, R.S. Brooks, George Hutson, Frank Sharp, and James Elliott all left heart-wrenching notes behind for their loved ones, some of which recorded the time. The letters were found on their bodies when the rescuers finally reached them.

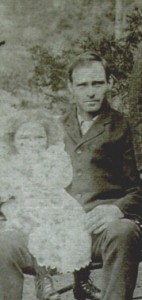

Jacob L. Vowell, husband of Sarah Ellen and father of seven children (one of whom, Eddie, had died in early childhood), penciled several notes as time passed. With him dying slowly was his 14-year-old son Harvey Elbert.

Jacob L. Vowell, husband of Sarah Ellen and father of seven children (one of whom, Eddie, had died in early childhood), penciled several notes as time passed. With him dying slowly was his 14-year-old son Harvey Elbert.

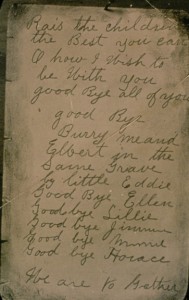

We are shut up in the head of the entry with of little air and the bad air is closing in on us fast and it is now about 12 o’clock. Dear Ellen, I have to leave you in bad condition. But dear wife, set your trust in the Lord to help you raise my little children. Ellen take care of my little darling Lily. Ellen, little Elbert said he had trusted in the Lord. Chas. Wood said he was safe if he never lives to see the outside again, he would meet his mother in heaven. If we never live to get out we are not hurt but only perished for air. There is but a few of us here and I don’t know where the other men is. Elbert said for you all to meet him in heaven, All the children meet with us both.

Ellen, darling Good Bye for us both. Elbert said the lord had saved him. Do the best you can with the children. We are all praying for air to support us but it is getting so bad without any air. Horace, Elbert said for you to wear his shoes and clothing. It is now 1/2 past 1.

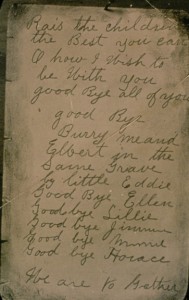

Powell Harmon’s watch is now in Andy Woods hand. Ellen, I want you to live right and come to heaven. Rais the children the best you can. O how I wish to be with you. Good Bye to all of you Good Bye. Burry me and Elbert in the same grave by little Eddy.

Powell Harmon’s watch is now in Andy Woods hand. Ellen, I want you to live right and come to heaven. Rais the children the best you can. O how I wish to be with you. Good Bye to all of you Good Bye. Burry me and Elbert in the same grave by little Eddy.

Good Bye Ellen

Good bye Lillie

Good bye Jimmie

Good bye Minnie

Good bye Horace

We are together. Is 25 minutes after Two. There is a few of us are alive yet

Good bye

JAKE & ELBERT

Oh God for one more breath. Ellen, remember me as long as you live. Good Bye Darling

Ellen lost not just her husband and son, but also two brothers in the disaster. The entire community was devastated. Only three adult men were left alive in the town. Hundreds of women were widowed and between 800 and 1,000 children were orphaned.

All of the recovered bodies were laid out next to the railroad for the families to claim. Eighty-nine of the miners were buried in the Fraterville Miners’ Circle in Leach Cemetery. The obelisk in the center records all 184 names of the identified miners. Some of the other victims were buried at Longfield Cemetery.

All of the recovered bodies were laid out next to the railroad for the families to claim. Eighty-nine of the miners were buried in the Fraterville Miners’ Circle in Leach Cemetery. The obelisk in the center records all 184 names of the identified miners. Some of the other victims were buried at Longfield Cemetery.

The bodies of 30 itinerant miners remained unclaimed and were buried next to the railroad spur line, marked by fieldstones or not at all. That land would eventually become the backyard of Owen Bailey, a retired Briceville miner who is now 96 years old. When the non-profit Coal Creek Watershed Foundation was established in 2000, Bailey told them about the miners buried in his backyard.

On Friday morning, archaeologists from the University of Tennessee, accompanied by students from Briceville Elementary, used ground-penetrating radar to confirm his story.

The foundation has erected a historic marker next to the itinerant miners’ graveyard.

“Early Welch [sic] miners in the area had many superstitions, and spirits of the itinerant miners are said to still be calling for family members to identify them,” the marker reads.

“On a clear night when the wind is blowing and the moon is full, listen carefully and you may hear them whispering their names.”

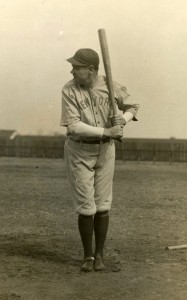

The wool jersey Babe Ruth wore the first year he played for the New York Yankees sold at auction today for $4,415,658, the highest price ever paid for a piece of sports memorabilia. The previous record was set in December of 2010 when James Naismith’s founding rules of basketball sold for $4,338,500. It was sold by online auction specialists SCP Auctions to sports memorabilia specialists Lelands.com who plan to resell it privately.

The wool jersey Babe Ruth wore the first year he played for the New York Yankees sold at auction today for $4,415,658, the highest price ever paid for a piece of sports memorabilia. The previous record was set in December of 2010 when James Naismith’s founding rules of basketball sold for $4,338,500. It was sold by online auction specialists SCP Auctions to sports memorabilia specialists Lelands.com who plan to resell it privately. The only change made to the jersey after its manufacture was its sleeves were cut shorter. This isn’t a negative, however, because there are pictures of Ruth wearing the jersey in 1920 and the sleeves are already short. It’s therefore likely that he had them altered to his preference, which makes the cut sleeves a point in favor of the jersey’s authenticity.

The only change made to the jersey after its manufacture was its sleeves were cut shorter. This isn’t a negative, however, because there are pictures of Ruth wearing the jersey in 1920 and the sleeves are already short. It’s therefore likely that he had them altered to his preference, which makes the cut sleeves a point in favor of the jersey’s authenticity. Then there’s the year, a momentous, even legendary year in baseball history whose repercussions were still being keenly felt as recently as 2004. On December 26, 1919, Harry Frazee, theatrical impresario and owner of the Boston Red Sox, sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees for $125,000. According to the urban legend that grew around this disastrous trade, Frazee made the sale to finance the Broadway musical No, No, Nanette, but that show debuted in 1925. He did use money from the Ruth sale to finance a play called My Lady Friends from which Nanette was later derived, but that’s not why he sold Ruth, or at least it’s not the sole reason.

Then there’s the year, a momentous, even legendary year in baseball history whose repercussions were still being keenly felt as recently as 2004. On December 26, 1919, Harry Frazee, theatrical impresario and owner of the Boston Red Sox, sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees for $125,000. According to the urban legend that grew around this disastrous trade, Frazee made the sale to finance the Broadway musical No, No, Nanette, but that show debuted in 1925. He did use money from the Ruth sale to finance a play called My Lady Friends from which Nanette was later derived, but that’s not why he sold Ruth, or at least it’s not the sole reason.