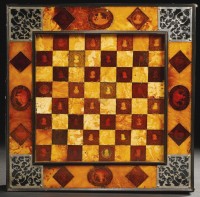

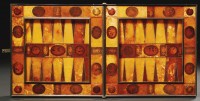

I can see why he wouldn’t have wanted to let it go until his head was separated from his neck. It’s that beautiful. Attributed to Georg Schreiber of Königsberg, Prussia, a 17th century master craftsman famed as the chess set maker to royalty, the game board is made of opaque white amber and translucent red amber on a wood chassis with an ebony superstructure, carved Roman-style portrait busts and chased silver accents. There’s a Nine Men’s Morris board on one side, a chess board on the other, and it opens up to reveal a diptych backgammon board. Inside it holds 14 game pieces of cream amber, with a white amber profile in the center overlaid with translucent red amber, and 14 pieces of translucent orange amber. The profiles are of all the kings of England from William the Conqueror to James I.

I can see why he wouldn’t have wanted to let it go until his head was separated from his neck. It’s that beautiful. Attributed to Georg Schreiber of Königsberg, Prussia, a 17th century master craftsman famed as the chess set maker to royalty, the game board is made of opaque white amber and translucent red amber on a wood chassis with an ebony superstructure, carved Roman-style portrait busts and chased silver accents. There’s a Nine Men’s Morris board on one side, a chess board on the other, and it opens up to reveal a diptych backgammon board. Inside it holds 14 game pieces of cream amber, with a white amber profile in the center overlaid with translucent red amber, and 14 pieces of translucent orange amber. The profiles are of all the kings of England from William the Conqueror to James I.

There is no signature on the board, so we can’t be absolutely certain that it was made by Georg Schreiber. The detail on this piece is one of a kind. No other boards have been found that are so elaborately decorated with allegorical scenes, busts, Latin and German proverbs, silver accents and painted metal underlays. However, Schreiber’s style is hard to mistake, and the many highly specific commonalities between this work and the only known game board to have been signed and dated by Schreiber put the attribution on very solid ground. The signed board is dated 1616. This board is dated 1607, which makes it the earliest Schreiber game board extant.

There is no signature on the board, so we can’t be absolutely certain that it was made by Georg Schreiber. The detail on this piece is one of a kind. No other boards have been found that are so elaborately decorated with allegorical scenes, busts, Latin and German proverbs, silver accents and painted metal underlays. However, Schreiber’s style is hard to mistake, and the many highly specific commonalities between this work and the only known game board to have been signed and dated by Schreiber put the attribution on very solid ground. The signed board is dated 1616. This board is dated 1607, which makes it the earliest Schreiber game board extant.

In the first half of the 17th century, Königsberg was the center of amber craftsmanship in Europe. The Sambia Peninsula on the Baltic Sea just northwest of Königsberg had been the primary source of amber in the West since antiquity, and in the Middle Ages, the amber trade was controlled by the Teutonic Order, which ruled the area from 1255 until 1525 when their Grand Master, Albrecht of Hohenzollern, converted to Lutheranism and secularized the Order’s former territories into the Duchy of Prussia. Instead of the rosary beads which had been the primary amber product under the Teutonic Knights, artisans in Königsberg, the capital of the new duchy, focused on crafting courtly objects — caskets, cups, inlay and of course, game boards — for the nobility and aristocracy of Europe.

In the first half of the 17th century, Königsberg was the center of amber craftsmanship in Europe. The Sambia Peninsula on the Baltic Sea just northwest of Königsberg had been the primary source of amber in the West since antiquity, and in the Middle Ages, the amber trade was controlled by the Teutonic Order, which ruled the area from 1255 until 1525 when their Grand Master, Albrecht of Hohenzollern, converted to Lutheranism and secularized the Order’s former territories into the Duchy of Prussia. Instead of the rosary beads which had been the primary amber product under the Teutonic Knights, artisans in Königsberg, the capital of the new duchy, focused on crafting courtly objects — caskets, cups, inlay and of course, game boards — for the nobility and aristocracy of Europe.

This particular game board with its exquisite craftsmanship and royal English theme may have first been owned by King James I, who ruled England at the time of the board’s creation and who is the last English king portrayed on the game pieces. These high quality objects were often used as diplomatic gifts. The Elector of Brandenburg, ruler of Prussia, could well have gifted it to King James.

The royal provenance is also hard to confirm, but we know that King Charles I was an avid chess player, not even interrupting his game when he was told that the Scots had changed sides and were supporting Parliament. According to the tradition that has accompanied the piece for centuries, King Charles I brought the game board to the scaffold on the day of his execution, January 30th, 1649. There he bequeathed it to William Juxon, the Bishop of London and the king’s personal chaplain who gave Charles the last rites before he was beheaded. Charles also gave Juxon the copy of the King James Bible he had brought to the scaffold with him, and he handed him his “George,” a figure of St. George slaying the dragon that is part of the accoutrements of the Order of the Garter, with the request that Juxon deliver it to the Prince of Wales.

The royal provenance is also hard to confirm, but we know that King Charles I was an avid chess player, not even interrupting his game when he was told that the Scots had changed sides and were supporting Parliament. According to the tradition that has accompanied the piece for centuries, King Charles I brought the game board to the scaffold on the day of his execution, January 30th, 1649. There he bequeathed it to William Juxon, the Bishop of London and the king’s personal chaplain who gave Charles the last rites before he was beheaded. Charles also gave Juxon the copy of the King James Bible he had brought to the scaffold with him, and he handed him his “George,” a figure of St. George slaying the dragon that is part of the accoutrements of the Order of the Garter, with the request that Juxon deliver it to the Prince of Wales.

By family tradition, Juxon left the game board to his nephew and it stayed in the family for two generations before being passed down to the Hesketh family, who added Juxon to their name as part of the inheritance stipulations. The Heskeths have owned it ever since. It’s the estate of Frederick Fermor-Hesketh, 2nd Lord Hesketh, which is now selling the piece. The Bible was given by Lady Susannah, widow of Sir William Juxon, son of the bishop’s nephew, to their neighbors the Jones family of Chastleton House. The Jacobean manor is now owned by the National Trust, but the Bible remains in the collection there. The Scaffold George, as the insignia became known, did eventually make its way to Charles’ son and is now in the Royal Collection.

By family tradition, Juxon left the game board to his nephew and it stayed in the family for two generations before being passed down to the Hesketh family, who added Juxon to their name as part of the inheritance stipulations. The Heskeths have owned it ever since. It’s the estate of Frederick Fermor-Hesketh, 2nd Lord Hesketh, which is now selling the piece. The Bible was given by Lady Susannah, widow of Sir William Juxon, son of the bishop’s nephew, to their neighbors the Jones family of Chastleton House. The Jacobean manor is now owned by the National Trust, but the Bible remains in the collection there. The Scaffold George, as the insignia became known, did eventually make its way to Charles’ son and is now in the Royal Collection.

Other than the long oral tradition and the clear lines of descent from William Juxon, there is some documentary evidence supporting the dramatic King Charles I story. The inventory of the King’s possessions after his execution lists “A Paire of Tables [i.e. two game boards joined together to form a diptych] of White and Yellowe Amber garnished with silver.” Written below the entry is a line saying that it was sold to a creditor of the perpetually indebted Charles for £30. Creditors got first dibs in these fire sales. This is how many of them were “repaid” after the King’s death: they bought something from the royal collection with the expectation that they would be able to resell it at a profit and get some of their money back. (One item listed on the inventory that didn’t sell was Charles’ collection of Raphael’s tapestry cartoons.)

Other than the long oral tradition and the clear lines of descent from William Juxon, there is some documentary evidence supporting the dramatic King Charles I story. The inventory of the King’s possessions after his execution lists “A Paire of Tables [i.e. two game boards joined together to form a diptych] of White and Yellowe Amber garnished with silver.” Written below the entry is a line saying that it was sold to a creditor of the perpetually indebted Charles for £30. Creditors got first dibs in these fire sales. This is how many of them were “repaid” after the King’s death: they bought something from the royal collection with the expectation that they would be able to resell it at a profit and get some of their money back. (One item listed on the inventory that didn’t sell was Charles’ collection of Raphael’s tapestry cartoons.)

How could the game board have been sold to a creditor if Charles gave it to Bishop Juxon, you ask? By order of Parliament, Juxon was allowed to be with the King during his final days under “the same restraint as the King is,” in other words, confined to his rooms in Whitehall Palace. From January 27th, 1649, the day the King was sentenced, until January 31st, the day after the King was executed, William Juxon was being held by Parliament. As soon as he left the scaffold, Juxon was questioned by Parliamentary authorities. They confiscated everything the King had given him and questioned him about the last thing the King said to him (“Remember”). The next day they let him go.

How could the game board have been sold to a creditor if Charles gave it to Bishop Juxon, you ask? By order of Parliament, Juxon was allowed to be with the King during his final days under “the same restraint as the King is,” in other words, confined to his rooms in Whitehall Palace. From January 27th, 1649, the day the King was sentenced, until January 31st, the day after the King was executed, William Juxon was being held by Parliament. As soon as he left the scaffold, Juxon was questioned by Parliamentary authorities. They confiscated everything the King had given him and questioned him about the last thing the King said to him (“Remember”). The next day they let him go.

Both the game board and the Scaffold George are listed on the inventory. So if these objects were confiscated and sold, how could Juxon have gotten the game board back and bequeathed it to his family? The plausible answer is he simply bought it back from the creditor. The creditor in question was William Latham, a wool merchant, who was doubtless far more interested in cashing out the decorative object than in keeping it, especially since he had had to pony up £30 to buy it from Parliament. We know for a fact that that’s what happened to the Scaffold George: it was purchased by a creditor who then sold it to royalists. They saw to it that George was returned to Charles II in keeping with his father’s request.

Both the game board and the Scaffold George are listed on the inventory. So if these objects were confiscated and sold, how could Juxon have gotten the game board back and bequeathed it to his family? The plausible answer is he simply bought it back from the creditor. The creditor in question was William Latham, a wool merchant, who was doubtless far more interested in cashing out the decorative object than in keeping it, especially since he had had to pony up £30 to buy it from Parliament. We know for a fact that that’s what happened to the Scaffold George: it was purchased by a creditor who then sold it to royalists. They saw to it that George was returned to Charles II in keeping with his father’s request.