A metal detectorist scanning farmland near Canterbury in Kent, southeast England, has unearthed a bronze helmet from the late Iron Age. Although seemingly modest compared to gold coin hoards and elaborately decorated ceremonial cavalry helmets, this is a find a major national importance. Only a few intact or near-intact Iron Age helmets have ever been discovered anywhere, only three of them in Britain (including this badass horned one fished out of the Thames in the 19th century) and only one of them, this one, of this particular design. It’s also one of the only helmets whose archaeological context was preserved and examined by professionals, thanks to the responsible actions of the finder (who wishes to remain anonymous). This turned out to be enormously important because the excavation revealed that the helmet is one of a kind in another way too.

A metal detectorist scanning farmland near Canterbury in Kent, southeast England, has unearthed a bronze helmet from the late Iron Age. Although seemingly modest compared to gold coin hoards and elaborately decorated ceremonial cavalry helmets, this is a find a major national importance. Only a few intact or near-intact Iron Age helmets have ever been discovered anywhere, only three of them in Britain (including this badass horned one fished out of the Thames in the 19th century) and only one of them, this one, of this particular design. It’s also one of the only helmets whose archaeological context was preserved and examined by professionals, thanks to the responsible actions of the finder (who wishes to remain anonymous). This turned out to be enormously important because the excavation revealed that the helmet is one of a kind in another way too.

Our anonymous metal detecting friend has some familiarity with archaeological practices because he had been a volunteer for the Canterbury Archaeological Trust. The Trust’s Finds Manager, Andrew Richardson, was previously the Finds Liaison Officer (the expert to whom members of the public bring historical finds to record them for the Portable Antiquities Scheme which is a necessary first step in the process of declaring a find treasure according to the UK’s Treasure Act) for Kent. Richardson knew the finder personally from his days as the Kent FLO, so when in October of this year he got a phone call from the finder claiming to have made “significant discovery” of a “Celtic bronze helmet,” Richardson agreed to go check out it. He was doubtful that it could really be an Iron Age helmet — no such helmets have ever been found in Kent before — but when he went to the finder’s house the next day, he indeed found a 1st century B.C. bronze helmet, a brooch from the same period, a bronze spike that was probably mounted on top of the helmet so a plume could be attached to it and a charred bone fragment.

Richardson agreed to go check out it. He was doubtful that it could really be an Iron Age helmet — no such helmets have ever been found in Kent before — but when he went to the finder’s house the next day, he indeed found a 1st century B.C. bronze helmet, a brooch from the same period, a bronze spike that was probably mounted on top of the helmet so a plume could be attached to it and a charred bone fragment.

The bone fragment suggested the helmet might have accompanied a burial, perhaps of a warrior or military leader. Richardson, the finder and the various authorities to whom they reported the discovery as possible treasure, agreed the find site should be promptly excavated. The finder had wisely marked the spot, placing a bag of lead fishing weights in the hole left by the helmet before backfilling it. This made the place easy to find and kept the archaeological context of the discovery intact.

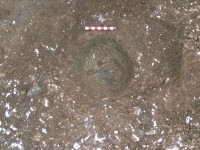

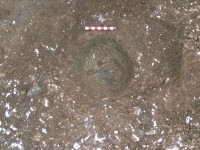

What they found was not a glamorous burial with military regalia, but a shallow oval pit cut into the chalk landscape. A green impression left by the copper alloy of the helmet during its 2000 years in the ground marked the burial spot within the pit. Fragments of the metal sheeting were still attached to the soil and you can clearly see a dense area in the middle which is what’s left of the rounded top of the helmet, which corroded over time leaving behind a hole.

What they found was not a glamorous burial with military regalia, but a shallow oval pit cut into the chalk landscape. A green impression left by the copper alloy of the helmet during its 2000 years in the ground marked the burial spot within the pit. Fragments of the metal sheeting were still attached to the soil and you can clearly see a dense area in the middle which is what’s left of the rounded top of the helmet, which corroded over time leaving behind a hole.

Archaeologists found a number of charred bone fragments as well, all within the helmet impression. That means the human remains were not buried with the helmet, but rather inside of it. The helmet was turned upside down and used an urn, basically. Judging from the location of the brooch above the bone fragments, the cremains were probably placed in a leather or fabric bag, now long decayed away, which was closed at the top with the brooch. The bag was placed inside the helmet either right before or right after it was buried in the eastern half of the oval pit. There’s no evidence of a grave marker and no evidence of any other burials nearby. Either this is a cemetery with widely spaced out plots or this was the sole grave.

If late Iron Age helmets are rare in England, late Iron Age helmet burials are unheard of. This is the first one ever discovered in Britain and the only other helmet burial we know of was found in Poland. If the detectorist had not noticed the bone or not properly marked the site for archaeologists to return to, we would never have known just how unique a find this is.

If late Iron Age helmets are rare in England, late Iron Age helmet burials are unheard of. This is the first one ever discovered in Britain and the only other helmet burial we know of was found in Poland. If the detectorist had not noticed the bone or not properly marked the site for archaeologists to return to, we would never have known just how unique a find this is.

As it is, it’s nothing short of miraculous that the helmet survived. The archaeological excavation found two deep plough furrows on either side of the helmet impression, a result of years of farming. The rim of the helmet is a little dented and battered, probably from contact with one of the makers of those furrows. Had a plough moved a few inches offset to the  right or left, the helmet would have been chewed up and scattered over this large field. Had the finder not found it when he did, there’s a good chance it would have met that fate in the future since the field is still actively farmed.

right or left, the helmet would have been chewed up and scattered over this large field. Had the finder not found it when he did, there’s a good chance it would have met that fate in the future since the field is still actively farmed.

Initial analysis, including laser scans, of the helmet by experts at the University of Kent and the British Museum indicate that the helmet was probably not locally made. It’s most likely of Gaulish manufacture and given how busy a time the 1st century B.C. was, there are any number of ways that it might have made its way to Britain. British mercenaries went to Gaul to fight on both sides during Caesar’s wars of conquest. Caesar and his troops fought in Britain in 55-54 B.C. They landed on the shores of Kent, in fact, just a few miles from where the helmet was found so perhaps it came with them.

The helmet will remain at the British Museum for further study while the process of determining whether this find qualifies as treasure continues. Unlike the Crosby-Garret helmet which so tragically slipped through a loophole of the Treasure Act, the fact that a brooch was found with this helmet is going to ensure it’s declared treasure because two pieces of ancient base metalwork qualify as treasure whereas just one, no matter how spectacular, does not. Once it’s declared treasure, a market value will be assessed and a local museum, in this case Canterbury Museum, will be given the first chance to purchase it.