A commercial refrigeration container normally used to transport perishable foodstuffs on the backs of trucks or stacked on cargo ships has been cleverly enlisted in the preservation of delicate archaeological remains at an important historical site in Lübeck, Germany.

Lübeck’s historic Old Town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its layout, planned from the earliest days of its founding in the mid-12th century, and large number of surviving medieval buildings. Even with 20% of the Old Town destroyed in World War II, Lübeck still has more than 1,000 listed buildings, characteristic back courtyards and a thick network of alleys from the Middle Ages.

Because of its dense history, before a major construction project to build luxury housing in the old merchant’s borough could begin, an equally major archaeological survey of the area had to clear the site first. This wasn’t a hasty six-week rush job (*cough* Drumclay Crannog *cough*). Excavation began in 2009 and is slated to end in 2014. In 2012, archaeologists made an incredible find: a wooden storage cellar from around 1180, less than 40 years after the founding of the town (1143) and 60 years before the alliance with Hamburg (1241) that would form the kernel of the future Hanseatic League.

Because of its dense history, before a major construction project to build luxury housing in the old merchant’s borough could begin, an equally major archaeological survey of the area had to clear the site first. This wasn’t a hasty six-week rush job (*cough* Drumclay Crannog *cough*). Excavation began in 2009 and is slated to end in 2014. In 2012, archaeologists made an incredible find: a wooden storage cellar from around 1180, less than 40 years after the founding of the town (1143) and 60 years before the alliance with Hamburg (1241) that would form the kernel of the future Hanseatic League.

It’s one of the largest and best-preserved medieval cellars in Europe, and remains of hops and cereals have been found indicating it was used to store ingredients for the production of beer. Just 30 years before this cellar was built, the first written description of hops’ preservative power as an additive to beer appeared in the medicinal text Physica Sacra by Hildegard of Bingen, mystic, musician, healer, abbess and as of December 2012, one of only four women named Doctor of the Church. The 12th century was an important transitional time in the political and economic history of beer as well. Secular princes increasingly took control of the brewing business from the monasteries that had been the traditional producers. The merchants of northern Germany, a burgeoning new social class not bound by feudal or monastic regulation, also got into brewing and trading beer.

It was a dangerous gig. You need long, steady fires to brew and in a time when entire cities were built of wood, one home brewing operation could burn the town to the ground. Municipal laws were promulgated preventing home brewing and transferring the industry out of individual houses and into stone communal brew houses which also served as bakeries. I can see masonry around the wooden elements in the pictures, so perhaps the Lübeck structure was a communal brewhouse/bakehouse cellar. That could well be later construction, though, and this the cellar of a wooden home brew operation with the remains of beer-making ingredients which has somehow survived devastation by fire for more than 800 years, several years of which included active aerial bombings. It’s an incredibly rare and important find.

It was a dangerous gig. You need long, steady fires to brew and in a time when entire cities were built of wood, one home brewing operation could burn the town to the ground. Municipal laws were promulgated preventing home brewing and transferring the industry out of individual houses and into stone communal brew houses which also served as bakeries. I can see masonry around the wooden elements in the pictures, so perhaps the Lübeck structure was a communal brewhouse/bakehouse cellar. That could well be later construction, though, and this the cellar of a wooden home brew operation with the remains of beer-making ingredients which has somehow survived devastation by fire for more than 800 years, several years of which included active aerial bombings. It’s an incredibly rare and important find.

But how to preserve such rare organic survivals quickly and carefully enough to give researchers a chance to study them thoroughly with as little loss as possible? As soon as the cellar was exposed to air it was in danger. Usually archaeologists have to keep wooden artifacts constantly wet, or find a massive freeze dryer or spend years replacing the water with polyethylene glycol. These methods are inconvenient, expensive and require transportation before conservation.

But how to preserve such rare organic survivals quickly and carefully enough to give researchers a chance to study them thoroughly with as little loss as possible? As soon as the cellar was exposed to air it was in danger. Usually archaeologists have to keep wooden artifacts constantly wet, or find a massive freeze dryer or spend years replacing the water with polyethylene glycol. These methods are inconvenient, expensive and require transportation before conservation.

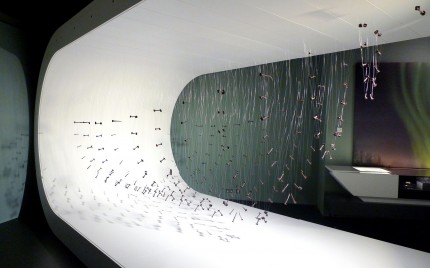

A refrigerated container, on the other hand, can be transported on site within 24 hours, is big enough to store a whole cellar, and has a wide range of environmental controls. A Maersk Container Industry Star Cool container, for instance, not only has precision temperature controls, but also an Automatic Ventilation feature which regulates airflow and relative humidity in the container and a Controlled Atmosphere option which monitors oxygen and carbon dioxide inside the container and maintains them at pre-set levels. Technology necessary to keep food from spoiling is also just what the doctor ordered to keep archaeological remains from decaying.

container, for instance, not only has precision temperature controls, but also an Automatic Ventilation feature which regulates airflow and relative humidity in the container and a Controlled Atmosphere option which monitors oxygen and carbon dioxide inside the container and maintains them at pre-set levels. Technology necessary to keep food from spoiling is also just what the doctor ordered to keep archaeological remains from decaying.

“Star Cool was chosen because of its extremely precise temperature and atmospheric control. Such precision is a must if you want to preserve sensitive cultural assets like wet organic structures,” says conservator Maruchi Yoshida who is associated with the Fraunhofer-Institute for Building Physics and Leibniz-Gemeinschaft to manage the reefer container project, ARCHe.

(Reefer in this case meaning refrigerated container, not the jazz musician kind of reefer.)

This is the first time a container has been used for archaeological preservation. Yoshida hopes to turn this pilot into a business, deploying units to newly discovered sites at a moment’s notice or to preserve cultural assets in danger from natural disasters or conflict.