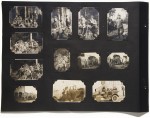

As his visit home for Thanksgiving two years ago was winding down, Dean Putney’s mother pulled out an old black photo album that he had never seen before. Inside were more than 700 pictures taken by his great-grandfather Walter Koessler when he was an officer in the German Reserve Artillery Battalion during World War I. Koessler was an architect and an accomplished photographer who was conscripted into the army while still in architecture school. He was sent to the Western Front where the army put his photographic skills to work, sending him up in biplanes and airships to take official aerial reconnaissance photos. However the vast majority of the pictures he took were informal shots of him and his comrades going about their daily life during all four years of the war: maneuvering cannons,

As his visit home for Thanksgiving two years ago was winding down, Dean Putney’s mother pulled out an old black photo album that he had never seen before. Inside were more than 700 pictures taken by his great-grandfather Walter Koessler when he was an officer in the German Reserve Artillery Battalion during World War I. Koessler was an architect and an accomplished photographer who was conscripted into the army while still in architecture school. He was sent to the Western Front where the army put his photographic skills to work, sending him up in biplanes and airships to take official aerial reconnaissance photos. However the vast majority of the pictures he took were informal shots of him and his comrades going about their daily life during all four years of the war: maneuvering cannons, bathing, about to slaughter a cow, playing cards in the trenches and, as the early optimism of the war decayed into years of mass butchery and attrition, dying in the trenches.

bathing, about to slaughter a cow, playing cards in the trenches and, as the early optimism of the war decayed into years of mass butchery and attrition, dying in the trenches.

After the war, Walter emigrated to the United States. He settled in Los Angeles and worked as an art director for the movies. That’s where he put together the 100-page photo album recording his life from 1914 to 1918. He also kept a box of around 60 stereographs (two slightly offset pictures side-by-side that create the illusion of three dimensionality when viewed through a  stereoscope like a View-Master) of the war and pre-war period and hundreds of the original negatives of both the photographs and the stereographs.

stereoscope like a View-Master) of the war and pre-war period and hundreds of the original negatives of both the photographs and the stereographs.

Most published and widely circulated pictures from World War I were taken by the Allies. Not that there weren’t plenty of military photographers and journalists on the German side as well; it’s just a history is written by the victors phenomenon. So extensive a personal record of the entire war compiled by a single officer who also had the chops to take properly composed, even beautiful, photographs is a unique resource. On top of that, Walter’s family kept the entire collection in excellent condition, especially the negatives which were rarely exposed to air or light and are so sharp, so rich that they look almost like new.

Dean Putney realized this precious record had to be shared with world. There were no captions on the pictures, just a few dates noted on the back of some, so Dean dedicated himself to research. He interviewed family, searched the web, contacted experts, even went in person to visit one of the sites depicted in the pictures so he could have an after shot to go with the devastated before.

A few months ago, Dean started a Tumblr to post the pictures as he began to scan them. The Walter Koessler Project is a great browse, but Dean wanted to do even more. He wanted to publish a high quality book of the collection that was the same size as the photo album with space for his research notes and for that, he needed money.

A few months ago, Dean started a Tumblr to post the pictures as he began to scan them. The Walter Koessler Project is a great browse, but Dean wanted to do even more. He wanted to publish a high quality book of the collection that was the same size as the photo album with space for his research notes and for that, he needed money.

He turned to Kickstarter, starting a project with a goal of $50,000 dollars on August 6th which would allow him to make a minimum order of 1000 copies with a publisher that does the kind of large format, specialty work Dean wanted to pay the proper respects to his great-grandfather’s war experience. Within two days he had raised $18,000. By the time I read about it on Boing Boing and contributed on August 9th, the project was more than halfway to its goal.

It has now exceeded that goal by $20,000 and there are still three weeks plus to go. Dean’s aim is to have the book in high resolution PDF form and in the casebound 11″ x 17″ coffee table format delivered in time for Christmas of this year. That’s contingent on everything going right, of course, and there could be unavoidable delays, but even if the coffee table book isn’t ready, some of the other rewards — PDF book, high resolution digital files of all the pictures, individual prints — will be.

It has now exceeded that goal by $20,000 and there are still three weeks plus to go. Dean’s aim is to have the book in high resolution PDF form and in the casebound 11″ x 17″ coffee table format delivered in time for Christmas of this year. That’s contingent on everything going right, of course, and there could be unavoidable delays, but even if the coffee table book isn’t ready, some of the other rewards — PDF book, high resolution digital files of all the pictures, individual prints — will be.

I don’t know what Dean plans to do with the extra money, but I hope it’s nothing more complicated than additional print orders because I’ve seen Kickstarters get weirdly rococo and fail to make good in response to an unexpected windfall. I think this is a phenomenal project, a history lover’s dream come true and a beautiful tribute. I also deeply appreciate Dean making the works freely available to bloggers and non-commercial media via a Creative Commons license as long as they are not used to promote war. Walter Koessler was a pacifist by the end of war. In this too Dean is paying homage to his great-grandfather and the horrors he experienced.

I don’t know what Dean plans to do with the extra money, but I hope it’s nothing more complicated than additional print orders because I’ve seen Kickstarters get weirdly rococo and fail to make good in response to an unexpected windfall. I think this is a phenomenal project, a history lover’s dream come true and a beautiful tribute. I also deeply appreciate Dean making the works freely available to bloggers and non-commercial media via a Creative Commons license as long as they are not used to promote war. Walter Koessler was a pacifist by the end of war. In this too Dean is paying homage to his great-grandfather and the horrors he experienced.