Ancient sources tell us that asbestos was used in antiquity for its fireproof properties primarily in textiles and candle wicks. The 2nd century Greek geographer Pausanias in Book I, Chapter 26 of his Description of Greece describes a golden lamp in the temple of Athena that burned all year on a single wick made of “Carpasian flax, the only kind of flax which is fire-proof.” Pliny the Elder dedicates a whole chapter of his Natural History (Book XIX, Chapter 4) to incombustible linen napkins woven out of asbestos fibers.

It is generally known as “live” linen, and I have seen, before now, napkins that were made of it thrown into a blazing fire, in the room where the guests were at table, and after the stains were burnt out, come forth from the flames whiter and cleaner than they could possibly have been rendered by the aid of water. It is from this material that the corpse-cloths of monarchs are made, to ensure the separation of the ashes of the body from those of the pile.

Pliny says the Greeks call these fibers asbestinon, meaning “inextinguishable.” He believes they grow in the heat of the Indian desert, not realizing that the fibrous substance is actually a mineral rather than a plant.

Asbestos continued to be used in the Christian era. Marco Polo mentions Tartars using a cloth made from fibers dug out of a mountain that whitens in fire, and the 10th century Persian geographer Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani, aka Ibn al-Fatiq, in his Concise Book of Lands records how clever scammers in Jerusalem sold Christian pilgrims little chunks of asbestos as pieces of the True Cross. The fact that they burned without being consumed by fire was seen as proof of authenticity. In the early 1800s, physics professor Jean Albini made a fireproof suit out of asbestos cloth and took it on a tour of Europe.

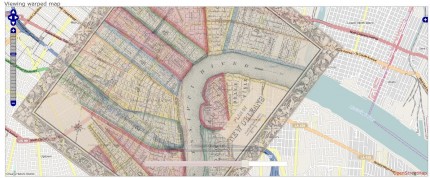

The use of asbestos in construction, however, has no such pedigree. That has been thought to be a relatively recent development of industrialization, first implemented in the late 19th century. Researchers from UCLA have discovered that Byzantine monks on Cyprus beat them to the punch by 700 years or so. Underneath 12th century wall paintings in the monastery of Enkleistra of St. Neophytos the UCLA team found a layer of chrysotile (white asbestos) in the finish coating of the plaster.

The use of asbestos in construction, however, has no such pedigree. That has been thought to be a relatively recent development of industrialization, first implemented in the late 19th century. Researchers from UCLA have discovered that Byzantine monks on Cyprus beat them to the punch by 700 years or so. Underneath 12th century wall paintings in the monastery of Enkleistra of St. Neophytos the UCLA team found a layer of chrysotile (white asbestos) in the finish coating of the plaster.

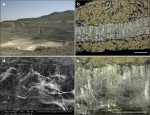

The researchers weren’t looking for asbestos. They were analyzing the paintings using an impressive panoply of technologies, among them infrared, UV and X-ray fluorescence imaging, and microsamples examined by scanning electron microscopy and gas chromatography mass spectrometry, to determine whether the materials changed over time. It was one of those microsamples, taken from an 1196 wall painting of the Enthroned Christ, that revealed the presence of chrysotile.

The researchers weren’t looking for asbestos. They were analyzing the paintings using an impressive panoply of technologies, among them infrared, UV and X-ray fluorescence imaging, and microsamples examined by scanning electron microscopy and gas chromatography mass spectrometry, to determine whether the materials changed over time. It was one of those microsamples, taken from an 1196 wall painting of the Enthroned Christ, that revealed the presence of chrysotile.

The sample was taken from the red frame of the book Christ is holding and consists of four layers: a dark brown top layer that was likely a varnish, an intense red cinnabar paint layer, the asbestos-rich orangey layer, and underneath them all, a plaster layer made mostly of plant fibers. Researchers believe the chrysotile was used to enhance the red cinnabar layer.

The sample was taken from the red frame of the book Christ is holding and consists of four layers: a dark brown top layer that was likely a varnish, an intense red cinnabar paint layer, the asbestos-rich orangey layer, and underneath them all, a plaster layer made mostly of plant fibers. Researchers believe the chrysotile was used to enhance the red cinnabar layer.

“[The monks] probably wanted to give more shine and different properties to this layer,” said UCLA archaeological scientist Ioanna Kakoulli, lead author of the new study, published online last month in the Journal of Archaeological Science. “It definitely wasn’t a casual decision — they must have understood the properties of the material.”

The closest asbestos mine was in the mountains about 40 miles inland from the coastal monastery. The monks, like their leader St. Neophytos, sought isolation in their monastery, so they weren’t likely to have traveled inland personally. They likely took advantage of a regional trade network to purchase their materials.

The closest asbestos mine was in the mountains about 40 miles inland from the coastal monastery. The monks, like their leader St. Neophytos, sought isolation in their monastery, so they weren’t likely to have traveled inland personally. They likely took advantage of a regional trade network to purchase their materials.

Although asbestos has only been found under that red cinnabar layer thus far, the UCLA team plans to return to the monastery to examine more of the wall paintings, and to look for asbestos that may have been missed in previous studies of other Cyprus wall paintings.