An unpublished song written by Felix Mendelssohn that has been lost for 142 years has been found in the United States. The signed manuscript was discovered by the current owner among his grandfather’s papers. The grandfather was a musician and a Mendelssohn fan, but we don’t know how this unique piece of music made it to the States into his collection.

An unpublished song written by Felix Mendelssohn that has been lost for 142 years has been found in the United States. The signed manuscript was discovered by the current owner among his grandfather’s papers. The grandfather was a musician and a Mendelssohn fan, but we don’t know how this unique piece of music made it to the States into his collection.

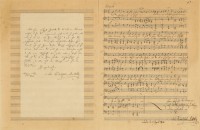

The song is a short 29 bars for alto voice and piano entitled Des Menschen Herz ist ein Schacht (A Man’s Heart Is Like a Mine). Mendelssohn wrote it in 1842, using the second stanza of the Friedrich Rückert poem Das Unveränderliche for lyrics. The verses describe the human heart as a mine that can produce precious metals or more utilitarian materials but can’t give anything that it doesn’t contain already. Rückert’s poems were very popular with composers like Schubert, Brahms and Mahler. There are more than 120 musical pieces set to his poetry.

This piece was a private commission from Johann Valentin Teichmann, a manager of Berlin’s Royal Theater who had lived in the Mendelssohn’s Berlin home from 1828 to 1831 when Felix was 19-22 years old. The Mendelssohns were a highly literature, cultured family who hosted a salon for artists at their house in Berlin for many years. Teichmann was part of this cultural community and worked closely with artists, playwrights, composers for decades in his management role at the Royal Theater.

Teichmann appears to have been too enthusiastic about the song for Mendelssohn’s taste. The composer wrote him a pointed letter on May 3rd, a few days after he had delivered the musical manuscript, asking Teichmann not to share the song with anyone else “because I have written it only at your request and only for you.” The letter lets him off the hook about having shown it already to one person, bookseller Wilhelm Besser. Mendelssohn says since the cat is already out of the bag that Teichmann can go ahead and give Besser a copy of the piece.

Teichmann appears to have been too enthusiastic about the song for Mendelssohn’s taste. The composer wrote him a pointed letter on May 3rd, a few days after he had delivered the musical manuscript, asking Teichmann not to share the song with anyone else “because I have written it only at your request and only for you.” The letter lets him off the hook about having shown it already to one person, bookseller Wilhelm Besser. Mendelssohn says since the cat is already out of the bag that Teichmann can go ahead and give Besser a copy of the piece.

Des Menschen Herz ist ein Schacht was never played in public, nor even published. It was only known to scholars from records of its sale at two auctions in Leipzig, one in 1862 and another in 1872. After that second sale, it disappeared from the record, only to crop up across the Atlantic nearly a century and a half later. The letter Felix wrote to Teichmann was found with the manuscript.

The owner has put the autographed musical manuscript and the letter up for auction at Christie’s in London. The pre-sale estimate is £15,000 – £25,000 ($25,320 – $42,200).

Whoever buys it, they won’t be able to keep it secret like Mendelssohn wanted. Now that it’s been rediscovered, the music is public record and has in fact already been performed. Alto Amy Williamson and pianist Christopher Glynn had the honor of playing Mendelssohn’s song for its first public performance on BBC Today:

[youtube=http://youtu.be/f-tb_m8SD04&w=430]