After 135 years, the skull of High Chief Ataï from the Pacific archipelago of New Caledonia has been returned to his homeland. In a ceremony on August 28th, France’s Overseas Territories Minister George Pau-Langevin gave the skull to Bergé Kawa, a chief in his own right and a direct descendant of Ataï. This is a righting of a wrong that has been very long in coming.

After 135 years, the skull of High Chief Ataï from the Pacific archipelago of New Caledonia has been returned to his homeland. In a ceremony on August 28th, France’s Overseas Territories Minister George Pau-Langevin gave the skull to Bergé Kawa, a chief in his own right and a direct descendant of Ataï. This is a righting of a wrong that has been very long in coming.

Captain Cook was the first European to encounter the main island in 1774. He named it New Caledonia because the cliffs of the east coast reminded him of the Scottish Highlands. French explorers mapped more of the archipelago, Bruni d’Entrecasteaux in 1792, Durmont d’Urville in 1827. British Protestant missionaries arrived in 1840 and with the discovery of sandalwood the next year, British merchants followed. French Catholic missionaries came in 1843. Religious conflict ensued with the Catholics ultimately coming out on top. New Caledonia was formally claimed as a French colony by Admiral Auguste Febvrier-Despointes in 1853, and two years later all land on the main island was declared property of the French state.

The French used it as a penal colony for the second half of the 19th century. An estimated 20,000 prisoners were transported to New Caledonia between 1864 and 1897, including 4,000 or so deported for their involvement in the Paris Commune and 100 Algerian insurrectionists. Most of them were put to work in the nickel and copper mines. While French authorities sent foreign laborers and settlers to the archipelago, they took indigenous people out. Many of the Kanak (a general name given to people from a wide variety of different tribes and clans with almost 30 mutually unintelligible languages) were enslaved or coerced into forced labor in Australia, Fiji, Canada, India, Japan, Malaysia and Chile, to name a few.

The French used it as a penal colony for the second half of the 19th century. An estimated 20,000 prisoners were transported to New Caledonia between 1864 and 1897, including 4,000 or so deported for their involvement in the Paris Commune and 100 Algerian insurrectionists. Most of them were put to work in the nickel and copper mines. While French authorities sent foreign laborers and settlers to the archipelago, they took indigenous people out. Many of the Kanak (a general name given to people from a wide variety of different tribes and clans with almost 30 mutually unintelligible languages) were enslaved or coerced into forced labor in Australia, Fiji, Canada, India, Japan, Malaysia and Chile, to name a few.

The ones were remained were in barely better straits. In 1864, convicts who were deemed worthy were freed and given land grants. More than 100,000 hectares of the richest farmland were deeded out to former convicts. In 1868, an order was promulgated forcing the indigenous people onto reservations, moving them inland close to the mountains where the land was barely arable. Many were made to work the plantations and ranches of French settlers without pay.

Under these kinds of pressure, it’s no surprise that conflicts exploded. Small revolts began in the 1850s but were quickly suppressed by overwhelming French force. It all came to a head in 1878. A drought in 1877 had taken a huge toll on the cattle, so the governor granted ranchers grazing rights on reservation lands. The stock were let loose on fallow fields, but there weren’t any fences. The cattle just walked on over to the farmed land and ate the yam and taro crops that were all the tribes had to live on. Already displaced from lands which defined their identities and to which they had a profound religious connection, the Kanaks couldn’t tolerate having what was left of their livelihoods threatened by French cows.

Under these kinds of pressure, it’s no surprise that conflicts exploded. Small revolts began in the 1850s but were quickly suppressed by overwhelming French force. It all came to a head in 1878. A drought in 1877 had taken a huge toll on the cattle, so the governor granted ranchers grazing rights on reservation lands. The stock were let loose on fallow fields, but there weren’t any fences. The cattle just walked on over to the farmed land and ate the yam and taro crops that were all the tribes had to live on. Already displaced from lands which defined their identities and to which they had a profound religious connection, the Kanaks couldn’t tolerate having what was left of their livelihoods threatened by French cows.

High Chief Ataï of the Petit Couli tribe sought out the French governor. The chief poured out a bag of soil in front of the governor and said, “This is what we had.” Then he dumped a bag of rocks out and said, “This is what you have left us.” The governor replied that they should protect their crops by building fences. Ataï responded: “When the taro eat the cattle, I’ll build the fences.”

Violent clashes ensued, with Kanaks attacking settlers and tribal leaders being imprisoned in retaliation. Ataï realized that localized revolts would go nowhere. He created an alliance between multiple tribes to fight the French. In June of 1878, the allied tribes launched an attack on troops and settlers. Their guerilla warfare was so successful that the French commander called for reinforcements from Indochina.

In August, Ataï and 500 warriors besieged a fort the French had built in La Foa on the southwest coast. At first the siege appeared to be going well for the Kanak side, but then the French managed to make a deal with Gelina, the High Chief of the Canala tribe, dividing the Kanak forces. Then the reinforcements from Indochina arrived. At the end of the month, a motley team of French regulars, convicts, former Communards who were promised their freedom in return for fighting on the side of a government they had once fought against so passionately, former Algerian rebels in the same position, and Kanak warriors from the Canala tribe surrounded Ataï’s army.

On September 1st, a detachment of French military encountered the chief, his three sons and his bard (the French anthropologists called him a “sorcerer”) Andia on the way back to the Kanak encampment. A Canala warrior with the French identified the chief from his shock of white hair. Communard hero Louise Michel, aka the Red Virgin, who had taught school during her New Caledonian exile and who was one of the only Communards to side with the Kanak, seeing in them the same struggle for liberty that she and her comrades had fought for, described the scene thus in her memoirs (pdf):

On September 1st, a detachment of French military encountered the chief, his three sons and his bard (the French anthropologists called him a “sorcerer”) Andia on the way back to the Kanak encampment. A Canala warrior with the French identified the chief from his shock of white hair. Communard hero Louise Michel, aka the Red Virgin, who had taught school during her New Caledonian exile and who was one of the only Communards to side with the Kanak, seeing in them the same struggle for liberty that she and her comrades had fought for, described the scene thus in her memoirs (pdf):

The traitor Segou faltered for a moment under the look of the old chief, but then, wanting it all to be over, he threw his short spear at Ataï and it pierced the old chief’s right arm. Ataï raised his axe in his left hand as his sons were shot down around him, one killed and the others wounded.

Andia lunged forward crying out, “Tango! Tango! (Cursed! Cursed!),” but he was shot dead instantly. Then Segou moved in against the wounded Ataï, and with his own axe struck blow after blow, the way he would have chopped at a tree.

Ataï fell, and Segou grabbed at his partially severed head. He struck him several more blows, and Ataï was finally dead. Seeing Ataï fall at Segou’s hands, the Kanaks unleashed their death cry in an echo to the mountains. The Kanaks love the brave.

The war would claim 1,000 Kanak lives and 200 French. Enslavement, disease and war took a terrible toll on the Kanak population. There were about 70,000 indigenous people living on the islands of New Caledonia when Cook arrived in 1774. By 1921, there were only 27,000 left.

The war would claim 1,000 Kanak lives and 200 French. Enslavement, disease and war took a terrible toll on the Kanak population. There were about 70,000 indigenous people living on the islands of New Caledonia when Cook arrived in 1774. By 1921, there were only 27,000 left.

The heads of Ataï, Andia and Ataï’s adolescent son were all severed, as was one of Ataï’s hands. Ship’s Lieutenant Servant received Andia’s head and Ataï’s head and hand from Segou and sold them for 200 francs to Dr. Navarre, a naval doctor. He packed the remains in tin boxes filled with phenol and shipped them to Professor Paul Broca, founder and president of the Anthropological Society of Paris (SAP). According to the minutes of SAP’s 396th meeting held on October 23, 1879 (Page 616 here), they arrived in a “perfect state of conservation. They emit no odor and we hope that the brain, even though they’re still in their skulls, will still be good for study.” Professor Broca:

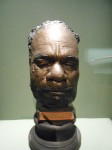

The magnificent head of the chief Ataï draws the most attention. It is very expressive; the forehead is especially very beautiful, very high and very wide. The hair is completely woolly, the skin completely black. The nose is very platyrrhine, as wide as it is high. The hand, broad and powerful, is very well-formed, except for one finger that is retracted due to an old injury. Palmar creases are similar to ours.

Andia’s head gets the same treatment, although it’s worse in some ways because it seems he suffered from some form of dwarfism so there’s a lot of gross talk about how savages see deformity.

Chief Ataï’s head was cast in bronze by Félix Flandinette, after which it was stripped of flesh and that brain they were so keen to get a look at, and the skull was kept with the SAP collection of skulls in the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. In 1951, SAP’s skull collection was transferred to the Musée de l’Homme where they’ve been kept in a cabinet for decades. Ataï’s death mask has been on display, but Ataï’s and Andia’s skulls never have been.

Chief Ataï’s head was cast in bronze by Félix Flandinette, after which it was stripped of flesh and that brain they were so keen to get a look at, and the skull was kept with the SAP collection of skulls in the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. In 1951, SAP’s skull collection was transferred to the Musée de l’Homme where they’ve been kept in a cabinet for decades. Ataï’s death mask has been on display, but Ataï’s and Andia’s skulls never have been.

Nonetheless, their treatment as specimens was and is deeply offensive to the Kanak. It has played a part in the consistent tension between New Caledonia and France even after the 1998 Noumea Accord, which granted some measure of autonomy to the territory along with the promise of a referendum on independence by 2018.

“These remains bring us back to our own reality: we are two peoples, two cultures which have never ceased to clash with each other and still clash today,” Kawa said [at the return ceremony].

“We were ravaged by the French state. It is therefore up to the French state to give us back our property,” he added.