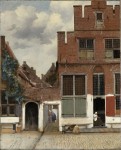

The exact street in Delft that Johannes Vermeer depicted in his 1658 painting View of Houses in Delft, better known as The Little Street, has been identified. It’s the Vlamingstraat, at the current house numbers 40 and 42, and even though the original buildings are gone, it’s eerie how similar the modern scene is to the 17th century one even though the details are very different.

The exact street in Delft that Johannes Vermeer depicted in his 1658 painting View of Houses in Delft, better known as The Little Street, has been identified. It’s the Vlamingstraat, at the current house numbers 40 and 42, and even though the original buildings are gone, it’s eerie how similar the modern scene is to the 17th century one even though the details are very different.

The Little Street can be regarded as “the earliest ‘portrait’ of the exterior of an ordinary house in northern European art”, according to Grijzenhout. It represents yet another indication of Johannes Vermeer’s innovation.

For nearly a century, scholars have debated whether The Little Street depicts a real pair of buildings or if it was conjured up in Vermeer’s imagination. The most widely accepted theory was that it represented a view from the inn owned by Vermeer, the Mechelen. His back windows overlooked almshouses in Voldersgracht, although the scene would not have been quite as in the painting so the artist must have produced his own interpretation. The almshouses were demolished in 1661 and a 20th century building now houses the Vermeer Centrum, which presents reproductions of the artist’s work.

University of Amsterdam professor of Art History Frans Grijzenhout tossed out the theory and found the site by consulting what some might consider a painfully mundane city record from 1667: the ledger of the dredging of the canals in the town of Delft, also known as the quay dues register. The register records the taxes paid by everyone with a canal-front home for the dredging of the canal and maintenance of the quay. Because homeowners only paid taxes for the canal works in front of their property, the ledger is meticulously precise about the width every house and alley between them, accurate to around 15 centimeters (6 inches).

University of Amsterdam professor of Art History Frans Grijzenhout tossed out the theory and found the site by consulting what some might consider a painfully mundane city record from 1667: the ledger of the dredging of the canals in the town of Delft, also known as the quay dues register. The register records the taxes paid by everyone with a canal-front home for the dredging of the canal and maintenance of the quay. Because homeowners only paid taxes for the canal works in front of their property, the ledger is meticulously precise about the width every house and alley between them, accurate to around 15 centimeters (6 inches).

Grijzenhout found a property on the Vlamingstraat, a lower-end neighborhood in eastern Delft, which had two houses 6.3 metres (about 21 feet) wide separated by two alleys about 1.2 meters (four feet) wide. Additional historical research, Google Maps data and analysis of the modern-day location confirmed that Vlamingstraat 40-42 fits. No other property in Delft matches the unique configuration in The Little Street.

The houses that stand on the site now were built in the late 1800s. The reason the painting and street today look alike even though the buildings are so different is that bricked entryway into the alley next to the house on the right. It’s a skinnier opening than it used to be thanks to the larger house on the left, but it is still recognizable.

The houses that stand on the site now were built in the late 1800s. The reason the painting and street today look alike even though the buildings are so different is that bricked entryway into the alley next to the house on the right. It’s a skinnier opening than it used to be thanks to the larger house on the left, but it is still recognizable.

Grijzenhout also discovered during his research that the house on the right of the painting was owned by Ariaentgen Claes van der Minne, Vermeer’s widowed aunt. She sold tripe and that alley next to her house was nicknamed the Penspoort or Trip Gate after her business. Vermeer’s mother and sister lived across the canal from the aunt, so this was a view he must have seen  very many times. It’s even possible that the figures in the painting are family members; maybe that’s his aunt working in the doorway of her house. The personal connection explains why he selected this scene to paint. Out of the 35 known surviving works by Vermeer, just two of them are townscapes, both of them in Delft. The second is View of Delft (1660-1) and it’s more of a skyline scene. It is now part of the permanent collection of the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague.

very many times. It’s even possible that the figures in the painting are family members; maybe that’s his aunt working in the doorway of her house. The personal connection explains why he selected this scene to paint. Out of the 35 known surviving works by Vermeer, just two of them are townscapes, both of them in Delft. The second is View of Delft (1660-1) and it’s more of a skyline scene. It is now part of the permanent collection of the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague.

The Little Street and the discovery of its location are the focus of an exhibition running through March 13th, 2016, at the Rijksmuseum. After that, the exhibition will move to the Museum Prinsenhof Delft from March 25th through July 17th, 2016. The Museum Prinsenhof Delft is thrilled to host the first Vermeer painting to visit the city in 60 years, and for it to be a painting so important to the history of the city makes it all the more special. Visitors to the museum will be able to see the painting and then walk in Vermeer’s footsteps to the street itself. The museum is going all out to give tourists the full Vermeer experience, creating walking routes and a virtual reality app that will put people in the middle of Vermeer’s Delft.

Google Art Project has put together a neat virtual exhibition that combines high resolution views of the painting with Google Street View tours of the Vlamingstraat location.