Nestled in the northern foothills of Mount Olympus, the ancient town of Dion was perfectly situated for sacrifices to the gods. It was a lot easier to carry animals to the base of the mountain than to climb its nearly 10,000-foot heights. The first known altar to Zeus Olympios was built in Dion in the 10th century B.C.

Nestled in the northern foothills of Mount Olympus, the ancient town of Dion was perfectly situated for sacrifices to the gods. It was a lot easier to carry animals to the base of the mountain than to climb its nearly 10,000-foot heights. The first known altar to Zeus Olympios was built in Dion in the 10th century B.C.

The small town grew into a prominent city under the Macedonians who revered it as the center of their religion. In the late 5th century B.C., Macedonian King Archelaus I founded the Olympian Games there, a yearly festival of the arts and athletic contents in honor of Olympian Zeus and his daughters the Muses.  Top athletes and artists flocked to the festival from all over Greece. The kings of Macedon made sacrifices at the altar to ring in every new year (the end of September in the Macedonian calendar), celebrated their military victories and invoked the protection and support of Olympian Zeus before setting out on new adventures. Philip II of Macedon celebrated his successful siege and destruction of Olynthos in 348 B.C. at Dion. His son Alexander the Great sacrificed to the gods there before taking his conquering armies East. He also imported the worship of Isis from Egypt to Dion.

Top athletes and artists flocked to the festival from all over Greece. The kings of Macedon made sacrifices at the altar to ring in every new year (the end of September in the Macedonian calendar), celebrated their military victories and invoked the protection and support of Olympian Zeus before setting out on new adventures. Philip II of Macedon celebrated his successful siege and destruction of Olynthos in 348 B.C. at Dion. His son Alexander the Great sacrificed to the gods there before taking his conquering armies East. He also imported the worship of Isis from Egypt to Dion.

The strong association with Alexander the Great served Dion well under the Roman emperors. Octavian founded a colony there in 31 B.C., and later emperors in the 2nd and 3rd centuries lent it their support. In the waning days of the empire, Dion was still prominent as the seat of a bishopric. Bishops of Dion took part in important church synods (Serdike in 343 A.D. and Ephesos in 431 A.D.), but at the end of the 5th century the city fell to the armies of Ostrogoth King Theodoric the Great and it never recovered. It gradually lost importance and population due to a series of earthquakes and floods from the river Vaphyras. By the 10th century it was an abandoned ruin.

The strong association with Alexander the Great served Dion well under the Roman emperors. Octavian founded a colony there in 31 B.C., and later emperors in the 2nd and 3rd centuries lent it their support. In the waning days of the empire, Dion was still prominent as the seat of a bishopric. Bishops of Dion took part in important church synods (Serdike in 343 A.D. and Ephesos in 431 A.D.), but at the end of the 5th century the city fell to the armies of Ostrogoth King Theodoric the Great and it never recovered. It gradually lost importance and population due to a series of earthquakes and floods from the river Vaphyras. By the 10th century it was an abandoned ruin.

The ruins of Dion were identified as the ancient sacred city of the Macedonians in 1806, but organized excavations didn’t begin until 1928. There was a 30-year lapse in archaeological exploration between 1931 and 1960. Since 1973, Dr. Dimitrios Pandermalis has led excavations at the site, returning every summer with a team of archaeologists, students and volunteers from the modern village to brave the oppressive heat and humidity. They have expanded the excavation area considerably to include the ancient sanctuaries, graveyards, tumulus burials and the town center. Spared development, reconstruction and the potentially destructive fumbling of early archaeologists, Dion has proved an archaeological treasure trove. Thanks to its wetlands environment at the base of the mountain between two rivers, Dion’s remains have been well preserved by water and mud layers.

The ruins of Dion were identified as the ancient sacred city of the Macedonians in 1806, but organized excavations didn’t begin until 1928. There was a 30-year lapse in archaeological exploration between 1931 and 1960. Since 1973, Dr. Dimitrios Pandermalis has led excavations at the site, returning every summer with a team of archaeologists, students and volunteers from the modern village to brave the oppressive heat and humidity. They have expanded the excavation area considerably to include the ancient sanctuaries, graveyards, tumulus burials and the town center. Spared development, reconstruction and the potentially destructive fumbling of early archaeologists, Dion has proved an archaeological treasure trove. Thanks to its wetlands environment at the base of the mountain between two rivers, Dion’s remains have been well preserved by water and mud layers.

All that mud and water is no picnic for the archaeological team to have to dig through, but it’s been worth it. Excavators have unearthed the remains of sanctuaries dedicated to Olympian Zeus, Zeus Hypsistos, Demeter, Isis and Asclepius. There’s a Hellenistic theater, a Great Baths complex, a partially preserved 2nd century A.D. Roman theater, a Greek and Roman wall, a 5th century Christian basilica and several Roman-era villas, most notably the Villa of Dionysus discovered in 1987.

All that mud and water is no picnic for the archaeological team to have to dig through, but it’s been worth it. Excavators have unearthed the remains of sanctuaries dedicated to Olympian Zeus, Zeus Hypsistos, Demeter, Isis and Asclepius. There’s a Hellenistic theater, a Great Baths complex, a partially preserved 2nd century A.D. Roman theater, a Greek and Roman wall, a 5th century Christian basilica and several Roman-era villas, most notably the Villa of Dionysus discovered in 1987.

The Villa of Dionysus was built in the second half of the 2nd century as a complex with an elegant home, a shrine to Dionysus, a bathhouse, a library and storefronts. Archaeologists discovered a great many ancient artworks: sculptures, decorative elements from expensive furniture, and mosaics of exceptional quality. Among the most prized sculptures is a group of four seated men representing Epicurean philosophers, three students and one teacher identifiable by his bearded adulthood and the open scroll he holds. The heads of the students were recarved in the 3rd century AD to give them portrait features, possibly to make them look like members of the family who lived in the house at the time. Other artworks found in the house include a hauntingly beautiful portrait of Agrippina the Elder, mother of Nero, and a glorious 100 square meter floor mosaic in the banquet hall depicting the Epiphany of Dionysus.

The Villa of Dionysus was built in the second half of the 2nd century as a complex with an elegant home, a shrine to Dionysus, a bathhouse, a library and storefronts. Archaeologists discovered a great many ancient artworks: sculptures, decorative elements from expensive furniture, and mosaics of exceptional quality. Among the most prized sculptures is a group of four seated men representing Epicurean philosophers, three students and one teacher identifiable by his bearded adulthood and the open scroll he holds. The heads of the students were recarved in the 3rd century AD to give them portrait features, possibly to make them look like members of the family who lived in the house at the time. Other artworks found in the house include a hauntingly beautiful portrait of Agrippina the Elder, mother of Nero, and a glorious 100 square meter floor mosaic in the banquet hall depicting the Epiphany of Dionysus.

The mosaic is one of the finest of its kind and is believed to be a copy of a lost Hellenistic painting. The villa being in ruins, there has been great concern about preserving the mosaic. The authorities built a custom addition to the museum to house the mosaic in ideal conservation conditions, but money was hard to come by. That changed last year when the Onassis Foundation funded the removal of the mosaic from the villa to the new building. Here’s a behind the scenes view of the detachment, transportation and conservation of the Epiphany of Dionysus mosaic:

The mosaic is one of the finest of its kind and is believed to be a copy of a lost Hellenistic painting. The villa being in ruins, there has been great concern about preserving the mosaic. The authorities built a custom addition to the museum to house the mosaic in ideal conservation conditions, but money was hard to come by. That changed last year when the Onassis Foundation funded the removal of the mosaic from the villa to the new building. Here’s a behind the scenes view of the detachment, transportation and conservation of the Epiphany of Dionysus mosaic:

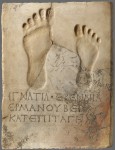

Now Dion is paying the Onassis Foundation back in the most wonderful way: by loaning the Onassis Cultural Center in New York City more than 90 artifacts — mosaics, sculptures, jewelry, medical implements, terracotta vessels, glassware — dating from the 10th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. Many of these pieces are in the US for the first time, and they are absolutely stunning. There’s the central panel of the Dionysus mosaic and

Now Dion is paying the Onassis Foundation back in the most wonderful way: by loaning the Onassis Cultural Center in New York City more than 90 artifacts — mosaics, sculptures, jewelry, medical implements, terracotta vessels, glassware — dating from the 10th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. Many of these pieces are in the US for the first time, and they are absolutely stunning. There’s the central panel of the Dionysus mosaic and  several of the masques around it, the sculptures of the four philosophers, that beautiful portrait of Agrippina, an Iron Age spiral brooch with textile fragments still attached to it, statues and stele of the gods. There are utilitarian artifacts as well, including a copper oil lamp decorated with the head of a panther and a 1st century B.C. copper speculum, which looks remarkably similar to the modern version.

several of the masques around it, the sculptures of the four philosophers, that beautiful portrait of Agrippina, an Iron Age spiral brooch with textile fragments still attached to it, statues and stele of the gods. There are utilitarian artifacts as well, including a copper oil lamp decorated with the head of a panther and a 1st century B.C. copper speculum, which looks remarkably similar to the modern version.

The Gods and Mortals at Olympus exhibition opened March 24th and runs through June 18th. They’ve really gone all out to put together a spectacular and content-rich show with cross-generational appeal. You can amble through the artifacts of Dion conversing with philosopher Simon Critchley, or lure your museum-resistant friends to the Museum Hacks series “for people who don’t like museums.” There’s even a videogame where children (and grown-ups!) can become the archaeologist excavating Dion. Entrance to the exhibition is free.

The Gods and Mortals at Olympus exhibition opened March 24th and runs through June 18th. They’ve really gone all out to put together a spectacular and content-rich show with cross-generational appeal. You can amble through the artifacts of Dion conversing with philosopher Simon Critchley, or lure your museum-resistant friends to the Museum Hacks series “for people who don’t like museums.” There’s even a videogame where children (and grown-ups!) can become the archaeologist excavating Dion. Entrance to the exhibition is free.