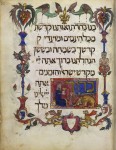

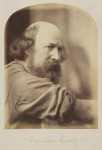

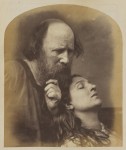

The National Portrait Gallery has acquired a rare album of albumen prints by Victorian photographer Oscar Gustav Rejlander, a pioneer of art photography and photomontage. The album contains 70 photographs of known and unknown people taken in the mid-1800s. They include portraits of Rejlander, his wife Mary, Hallam Tennyson, son of Lord Alfred Tennyson, poet and essayist Sir Henry Taylor, a number of unknown sitters and models representing allegorical themes like prayer, sadness and painting. Copies of some of the portraits in the album are in museums and private collections, but most of them were previously unknown to scholarship.

The National Portrait Gallery has acquired a rare album of albumen prints by Victorian photographer Oscar Gustav Rejlander, a pioneer of art photography and photomontage. The album contains 70 photographs of known and unknown people taken in the mid-1800s. They include portraits of Rejlander, his wife Mary, Hallam Tennyson, son of Lord Alfred Tennyson, poet and essayist Sir Henry Taylor, a number of unknown sitters and models representing allegorical themes like prayer, sadness and painting. Copies of some of the portraits in the album are in museums and private collections, but most of them were previously unknown to scholarship.

Born in Sweden around 1813, Rejlander trained as a painter in Rome and moved to England where he opened a portrait photography studio in 1850. In addition to the portraits of moneyed clients, Rejlander photographed street kids and prostitutes, some of whom modeled for his allegorical works. His experiments with techniques like double-exposure and photomontage were cutting edge and one of them, an allegory called The Two Ways of Life which shows two young men presented with views of the virtuous and decadent life, made him famous. He combined 32 of his own negatives in that

Born in Sweden around 1813, Rejlander trained as a painter in Rome and moved to England where he opened a portrait photography studio in 1850. In addition to the portraits of moneyed clients, Rejlander photographed street kids and prostitutes, some of whom modeled for his allegorical works. His experiments with techniques like double-exposure and photomontage were cutting edge and one of them, an allegory called The Two Ways of Life which shows two young men presented with views of the virtuous and decadent life, made him famous. He combined 32 of his own negatives in that  one montage; it took him six weeks to complete. The nudity on the sinful side caused some pearl-clutching, but Queen Victoria, who we now know had a keen appreciation for the carnal pleasures of marriage, liked it so much she bought a copy to give to Prince Albert. His innovations in the field earned him the title the father of art of photography.

one montage; it took him six weeks to complete. The nudity on the sinful side caused some pearl-clutching, but Queen Victoria, who we now know had a keen appreciation for the carnal pleasures of marriage, liked it so much she bought a copy to give to Prince Albert. His innovations in the field earned him the title the father of art of photography.

It’s not known who compiled the album. It was part of the estate of Surgeon Commander Herbert Ackland Browning whose father was connected by marriage to Dr. Marsters Kendal, surgeon to the future King Edward VII. Annotations in the album indicate the album was lent to the Prince of Wales, so it’s possible it came though Dr. Kendal directly from the artist who, according to one of the notes in the album, at first refused to sell until the buyer offered “£2.2.0 for the Swedish poor.” It remained in the Browning family for 140 years, unpublished and unrecognized, until they put it up for auction in 2014.

It’s not known who compiled the album. It was part of the estate of Surgeon Commander Herbert Ackland Browning whose father was connected by marriage to Dr. Marsters Kendal, surgeon to the future King Edward VII. Annotations in the album indicate the album was lent to the Prince of Wales, so it’s possible it came though Dr. Kendal directly from the artist who, according to one of the notes in the album, at first refused to sell until the buyer offered “£2.2.0 for the Swedish poor.” It remained in the Browning family for 140 years, unpublished and unrecognized, until they put it up for auction in 2014.

The album was sold by Morphets of Harrogate on September 11, 2014, for a hammer price of £70,000 ($101,000) to a Canadian buyer. In February of 2015, Culture Minister Ed Vaizey placed a temporary export bar on the album because its significance to the history of photography and 19th century art. Christopher Wright of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA), the body that made the recommendation that the export license not be immediately granted, explains the album’s unique historical import:

The album was sold by Morphets of Harrogate on September 11, 2014, for a hammer price of £70,000 ($101,000) to a Canadian buyer. In February of 2015, Culture Minister Ed Vaizey placed a temporary export bar on the album because its significance to the history of photography and 19th century art. Christopher Wright of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA), the body that made the recommendation that the export license not be immediately granted, explains the album’s unique historical import:

Rejlander was one of the most popular photographers of his day, famous for pioneering combination prints and for his illustrations in Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. This particular album, a rare survival, is known to have been shown to both Pope Pius IX and the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), who was an enthusiastic collector of his work.

The NPG already had 10 photographs by Rejlander in its collection, but the addition of this album greatly enhances its 19th century photography gallery.

The NPG already had 10 photographs by Rejlander in its collection, but the addition of this album greatly enhances its 19th century photography gallery.

Dr Phillip Prodger, Head of Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery, London, says: “The Rejlander album becomes one of the jewels in the crown of our already impressive collection of 19th century photographs. It transforms the way we think about one of Britain’s great artists. And it contains some of the most beautiful and expressive portraits of the Victorian era.”

The Rejlander album will go on display at the National Portrait Gallery in October. The NPG has already digitzed the prints from the album which can be seen on its website. If you’d like the turn the pages of the album and zoom in closer than the NPG photos allow (albeit with unfortunate watermarks), the auction company made a neat digital flipbook.

If the Flash album doesn’t work for you, here’s a pdf version.