Hundreds of graffiti on left on the walls of Richmond Castle by conscientious objectors during World War I will be preserved by English Heritage, thanks to the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Hundreds of graffiti on left on the walls of Richmond Castle by conscientious objectors during World War I will be preserved by English Heritage, thanks to the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Richmond Castle was built a few years after the Battle of Hastings by the Alan Rufus, a relative of William the Conqueror’s and the 1st Lord of Richmond. The remains of a hall block from the 1080s still stand, the most surviving 11th century architecture of any castle in England. In 1854 the  Duke of Richmond leased the castle, many parts of it now derelict, to the North York Militia. Barracks were constructed against the western wall and a reserve armory built near the castle gate.

Duke of Richmond leased the castle, many parts of it now derelict, to the North York Militia. Barracks were constructed against the western wall and a reserve armory built near the castle gate.

It was the 19th century armory which was put to use in World War I as a prison for conscientious objectors after conscription began in 1916. The castle was occupied by the northern Non-Combatant Corps, a support unit which allowed people with  religious or moral objections to killing to serve in non-combatant roles. That didn’t work for all the objectors, 16 of whom wanted no part of the war effort, combatant or no. In theory the conscription law had a “conscience clause” which allowed people with pacifist religious beliefs to be exempt from combat, but in practice exemptions were very hard to come by. Even members of a church denomination like the Quakers which had strictly upheld the principle of non-violence for hundreds of years at times under extreme persecution and duress, faced arrest and imprisonment.

religious or moral objections to killing to serve in non-combatant roles. That didn’t work for all the objectors, 16 of whom wanted no part of the war effort, combatant or no. In theory the conscription law had a “conscience clause” which allowed people with pacifist religious beliefs to be exempt from combat, but in practice exemptions were very hard to come by. Even members of a church denomination like the Quakers which had strictly upheld the principle of non-violence for hundreds of years at times under extreme persecution and duress, faced arrest and imprisonment.

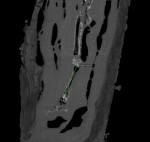

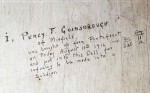

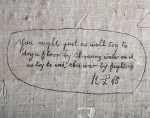

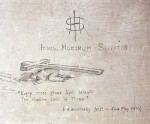

The Richmond Sixteen included people from different Christian denominations — Quakers, Methodists, International Bible Students (renamed Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1931) — and socialists. They were kept in eight small, damp cells on two floors of the old armory. Often they were forced to subsist on bread and water. They kept their spirits up by singing, discussing religion and politics, playing chess through a hole in the wall and decorating the walls that confined them with hundreds of graffiti. There are Bible verses, portraits of loved ones, hymns, political statements, a calendar and more.

The Richmond Sixteen included people from different Christian denominations — Quakers, Methodists, International Bible Students (renamed Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1931) — and socialists. They were kept in eight small, damp cells on two floors of the old armory. Often they were forced to subsist on bread and water. They kept their spirits up by singing, discussing religion and politics, playing chess through a hole in the wall and decorating the walls that confined them with hundreds of graffiti. There are Bible verses, portraits of loved ones, hymns, political statements, a calendar and more.

The Richmond Sixteen were moved from the castle on May 29th, 1916, to a military camp near Boulogne in France. As soon as they stepped foot on the camp, they were officially considered on active duty, which meant they would be subject to harsh military justice should they refuse to follow orders. Since everyone knew they weren’t going to follow any orders, the move to France was basically a gun to their head. When they declined to schlep supplies at the dock when ordered, they were court-martialed, found guilty and “sentenced to suffer death by being shot.” Their sentences were quickly commuted to 10 years’ hard labour.

The Richmond Sixteen were moved from the castle on May 29th, 1916, to a military camp near Boulogne in France. As soon as they stepped foot on the camp, they were officially considered on active duty, which meant they would be subject to harsh military justice should they refuse to follow orders. Since everyone knew they weren’t going to follow any orders, the move to France was basically a gun to their head. When they declined to schlep supplies at the dock when ordered, they were court-martialed, found guilty and “sentenced to suffer death by being shot.” Their sentences were quickly commuted to 10 years’ hard labour.

It turned out that Prime Minister Herbert Asquith had issued a secret order that none of the conscientious objectors in France were to be shot. He didn’t want them dead; he wanted people to think the military wouldn’t hesitate to shoot COs to death as a deterrent to anyone else thinking of asking for an exemption from service.

It turned out that Prime Minister Herbert Asquith had issued a secret order that none of the conscientious objectors in France were to be shot. He didn’t want them dead; he wanted people to think the military wouldn’t hesitate to shoot COs to death as a deterrent to anyone else thinking of asking for an exemption from service.

When the COs were shipped back to England, they had sentences to serve in civil prisons and work centers. For the rest of the war the Richmond Sixteen busted up rocks in a quarry near Aberdeen where the local newspapers referred to them as “degenerates.” When they were finally released, the “conscies” were widely reviled as cowards and treated with contempt. Finding a job and a place to live was a huge challenge.

When the COs were shipped back to England, they had sentences to serve in civil prisons and work centers. For the rest of the war the Richmond Sixteen busted up rocks in a quarry near Aberdeen where the local newspapers referred to them as “degenerates.” When they were finally released, the “conscies” were widely reviled as cowards and treated with contempt. Finding a job and a place to live was a huge challenge.

The graffiti they left on the walls of their Richmond Castle cells has survived for a hundred years, but conditions have been as unkind to it as people were to their creators. The 19th century armory was built lime-washed walls that were never intended to last. Water is leaking in through cracks in the roof and walls. Salts in the lime react to moisture, crystallizing and lifting the lime layer off the wall behind. As the lime flakes off, it takes the graffiti with it.

The graffiti they left on the walls of their Richmond Castle cells has survived for a hundred years, but conditions have been as unkind to it as people were to their creators. The 19th century armory was built lime-washed walls that were never intended to last. Water is leaking in through cracks in the roof and walls. Salts in the lime react to moisture, crystallizing and lifting the lime layer off the wall behind. As the lime flakes off, it takes the graffiti with it.

The Buildings Conservation and Research Team at Historic England have been studying the site since 2014, documenting temperature and humidity levels, analyzing the walls and wash, pinpointing the most threatened areas. They have laser scanned the walls and captured the graffiti with high resolution photographs. They didn’t have the funding to do the necessary repairs and conservation until this year. From 2016 to 2018, English Heritage will spend £365,400 to repair the

The Buildings Conservation and Research Team at Historic England have been studying the site since 2014, documenting temperature and humidity levels, analyzing the walls and wash, pinpointing the most threatened areas. They have laser scanned the walls and captured the graffiti with high resolution photographs. They didn’t have the funding to do the necessary repairs and conservation until this year. From 2016 to 2018, English Heritage will spend £365,400 to repair the  roof and walls, stop the water penetration and treat the graffiti in greatest danger. Once the walls have been stabilized enough to ensure people’s breath won’t harm the artwork, the cells will be open to the general public for the first time in 30 years.

roof and walls, stop the water penetration and treat the graffiti in greatest danger. Once the walls have been stabilized enough to ensure people’s breath won’t harm the artwork, the cells will be open to the general public for the first time in 30 years.

For more information about the Richmond Sixteen, the graffiti and the castle, see English Heritage’s website. Here are two short videos they made with fine shots of the interior.

Conserving the graffiti:

[youtube=https://youtu.be/d48ZhtKtQsY&w=430]

Inside the cells:

[youtube=https://youtu.be/F92G_bPoLqU&w=430]