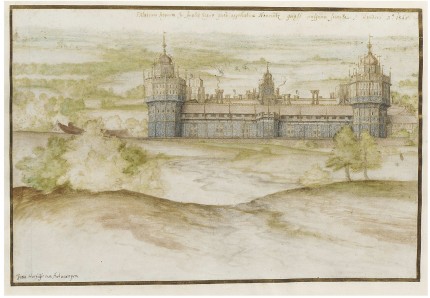

The Victoria and Albert museum has acquired a unique watercolor of Nonsuch Palace painted from life by Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel. He signed and dated it 1568, which makes it the earliest surviving depiction of the grand palace and one of the earliest surviving English landscape watercolors. Only six contemporary depictions of Nonsuch are known, and this one is the most detailed and accurate. They are all the more precious because the palace was destroyed 150 years after it was built. The watercolor was sold at auction to a foreign buyer, but a temporary export ban gave British institutions the change to keep this rare glimpse into a lost Renaissance architectural masterpiece. The price tag was a steep £1 million ($1,257,450). The V&A was able to raise the money with help from grants from the National Heritage Memorial Fund (NHMF) and the Art Fund.

Construction on the palace began in April of 1538, six months after the birth of Henry VIII’s obsessively desired son and heir, Edward. Unlike his other 13 palaces around London, this one was built from scratch, not an addition to a previous structure. Henry picked the location near Ewell in Surrey because it was next to his favorite hunting grounds. The fact that a village and church stood there was no deterrent. He paid compensation and demolished the structures to make room for a great Franco-Italianate palace whose splendour would outdo any other monarch’s (especially Henry’s archrival Francis I of France) grandest residence.

Covered in hundreds of elaborate stucco high reliefs bordered with carved and gilded slate, the palace was dubbed Nonsuch because it was sui generis, one of a kind. There was no other such palace in Europe. The reliefs in the inner courtyard depicted figures from Classical mythology and history. They were organized in three levels. On the top were Roman emperors, in the middle gods and goddesses, and on the bottom the Labours of Hercules on the west side of the courtyard and the Liberal Arts and Virtues on the east. On the south side was a relief of Henry VIII with his son Edward, a celebration of the Tudor dynasty as the culmination (at least in the king’s mind), of all those emperors, deities and muses.

The palace was unfinished when Henry VIII died in 1547 (all the important bits were done and it was entirely livable). Queen Mary I sold the palace to Henry Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel, in 1557 and he finally finished it. He’s the one who probably commissioned Joris Hoefnagel to paint the palace. Nonsuch returned to the crown in 1592, purchased by Elizabeth I who loved it and used it extensively. It remained a royal property until the Civil War. After the execution of Charles I in 1649, it was confiscated along with the rest of the crown’s property and sold.

With the restoration of the monarch in 1660, Nonsuch was returned to the crown. Charles II had little interest in the Renaissance masterpiece, and 10 years later he deeded it to his mistress, the tempestuous and profligate Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland and Countess of Castlemaine. In 1682, Barbara took it upon herself to demolish the palace and sell it off piecemeal to pay off her enormous gambling debts. It took years to take the whole thing apart, at least until 1688. As late as 1702, one of the turreted gate houses still stood.

With the restoration of the monarch in 1660, Nonsuch was returned to the crown. Charles II had little interest in the Renaissance masterpiece, and 10 years later he deeded it to his mistress, the tempestuous and profligate Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland and Countess of Castlemaine. In 1682, Barbara took it upon herself to demolish the palace and sell it off piecemeal to pay off her enormous gambling debts. It took years to take the whole thing apart, at least until 1688. As late as 1702, one of the turreted gate houses still stood.

Just to give you an idea of high on the “because people are crazy” scale the Duchess of Cleveland was, she didn’t even sell the stucco panels! They were busted up to bits and an estimated 100,000 fragments carted off somewhere. The first archaeological exploration of the site of the demolished palace in  1959 recovered more than 1,500 fragments with visible decoration and many more plain stucco fragments. Out of all those fragments a single panel was able to be partially reconstructed, that of a Roman soldier sitting next to his shield (now in the Museum of London). You can actually see a soldier and his shield on Hoefnagel’s watercolor, and it is located just above the spot where the fragments were discovered. This is a perfect example of why this one watercolor is so historically and culturally significant.

1959 recovered more than 1,500 fragments with visible decoration and many more plain stucco fragments. Out of all those fragments a single panel was able to be partially reconstructed, that of a Roman soldier sitting next to his shield (now in the Museum of London). You can actually see a soldier and his shield on Hoefnagel’s watercolor, and it is located just above the spot where the fragments were discovered. This is a perfect example of why this one watercolor is so historically and culturally significant.

Mark Evans, Senior Curator of Word and Image at the V&A, said: “Painted in 1568 by the last of the great Flemish illuminators and a foremost topographical artist of the day, this is a rare and beautiful work of outstanding importance. Among the earliest surviving English landscape watercolours, it brings to life one of the greatest monuments of the English Renaissance, now lost to us. We are delighted to acquire a picture of such quality and historical importance for our visitors to enjoy.”

The Joris Hoefnagel watercolor of Nonsuch Palace is now on display in the V&A’a British Galleries.