The introduction of photography in the mid-19th century had democratized portraiture, giving people who couldn’t afford to commission painters and miniaturists to immortalize them on canvas the opportunity to capture their image for a tiny fraction of the cost. Portraits could now be handed out like calling cards; in fact, they often were calling cards, as in the cartes de visite and later cabinet cards.

Oscar Wilde was an enthusiastic proponent of photographic portraits. Even before he made his literary bones with the plays and stories that would make him famous, he was already cutting a fine figure in society as a raconteur, wit and dandy, and his portraits emphasized his esthetic. He was captured in a variety of outfits and posed by some of the most famous photographers of the period, most notably a series of albumen prints taken by Napoleon Sarony of New York in 1882. Photos from the Sarony series have become iconic representations of Oscar Wilde.

Oscar Wilde was an enthusiastic proponent of photographic portraits. Even before he made his literary bones with the plays and stories that would make him famous, he was already cutting a fine figure in society as a raconteur, wit and dandy, and his portraits emphasized his esthetic. He was captured in a variety of outfits and posed by some of the most famous photographers of the period, most notably a series of albumen prints taken by Napoleon Sarony of New York in 1882. Photos from the Sarony series have become iconic representations of Oscar Wilde.

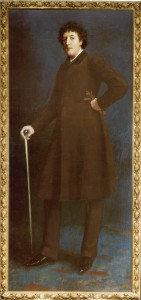

Around the same time, Wilde commissioned an oil-on-canvas portrait from US artist Robert Goodloe Harper Pennington. The life-sized, full-length portrait depicts Wilde in a classic elite power pose often seen in royal portraiture like Anthony van Dyck’s 1635 painting of Charles I at hunt, now in the Louvre. He stands with elegant nonchalance, one hand on his cane, the other, holding his gloves, on his hip. Pennington gave the portrait to Wilde and his new bride Constance as a wedding present in 1884.

Oscar Wilde loved the portrait, hanging it above the fireplace in his home in London. He published The Picture of Dorian Gray just a few years later in 1890. Perhaps his own experience standing for the Pennington portrait — Dorian’s was also a life-sized, full-length portrait — informed his writing. “It is horribly dull standing on a platform and trying to look pleasant,” Dorian complains to the artist Basil Hallward, the tedium of it driving Dorian to engage the corrupting influence of Lord Henry Wotton.

The came the disastrous libel suit. In 1895, Wilde sued the Marquess of Queensberry, father of his impetuous lover Lord Alfred Douglas, for leaving a calling card with a note calling Wilde a “posing sodomite.” Evidence of Oscar’s sexual liaisons with Douglas and other men was presented at trial, and instead of just losing the libel suit, Wilde was himself tried for “gross indecency” and was condemned to serve two years in solitary confinement with hard labour. The trial and conviction ruined Wilde’s reputation, his career and his life. Broke, shunned by his wife and children and a social pariah where he had once been toast of the town, Wilde died in Paris in 1900 at the age of 46.

The scandal quickly led to financial ruin. Wilde was declared bankrupt while awaiting trial and all his belongings were sold at auction to pay off creditors. The portrait was bought by his good friends Ernest and Ada Leverson (he had stayed at their house when the trial and scandal drove him into hiding). In a letter written less than a month after his release from Reading Gaol, Wilde connected the portrait to the blackened reputation of its subject: “I was quite conscious of the very painful position of a man who had in his house a life-sized portrait, which he could not have in his drawing-room as it was obviously, on account of its subject, demoralising to young men, and possibly to young women of advanced views.” He still loved it though, and got it back from the Leversons when he was released. He kept it in a room in Kensington, but died in exile never having seen the portrait again.

The scandal quickly led to financial ruin. Wilde was declared bankrupt while awaiting trial and all his belongings were sold at auction to pay off creditors. The portrait was bought by his good friends Ernest and Ada Leverson (he had stayed at their house when the trial and scandal drove him into hiding). In a letter written less than a month after his release from Reading Gaol, Wilde connected the portrait to the blackened reputation of its subject: “I was quite conscious of the very painful position of a man who had in his house a life-sized portrait, which he could not have in his drawing-room as it was obviously, on account of its subject, demoralising to young men, and possibly to young women of advanced views.” He still loved it though, and got it back from the Leversons when he was released. He kept it in a room in Kensington, but died in exile never having seen the portrait again.

After Wilde’s death, the portrait was kept by his literary executor, former lover and loyal friend Robert Ross. Robert Ross’ collection of books, manuscripts and assorted Wildeana including the Pennington portrait was sold in 1928, nine years after Ross’ death, to US collector William Andrews Clark. Clark acquired three other major collections of Wilde’s works and possessions, creating the largest Oscar Wilde collection in the world. That collection is now housed at UCLA’s William Andrews Clark Memorial Library.

For the first time in almost a century, the portrait will be returning the UK next year for the first exhibition dedicated to queer British art at the Tate Britain. This will be the first time the portrait that after his trial Oscar Wilde described as a “social incubus” will be on public display in Britain. It will be displayed next to the door of his prison cell in Reading Gaol.

Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson said the painting showed Wilde on the verge of success.

“It’s an extraordinary image of Wilde on the brink of fame, before imprisonment destroyed his health and reputation,” he said. “Viewing it next to the door of his jail cell will be a powerful experience that captures the triumph and tragedy of his career.”