Archaeologists with the Middle Kingdom Theban Project have rediscovered a large cache of mummification materials in the necropolis of Deir el-Bahari on the West Bank of the Nile at Luxor. The Spanish archaeological mission, led by Dr. Antonio Morales, found 56 amphorae and close to 300 linen packets of natron and other materials used in the embalming process in a well a few feet northeast of the entrance to the tomb of Ipi.

Archaeologists with the Middle Kingdom Theban Project have rediscovered a large cache of mummification materials in the necropolis of Deir el-Bahari on the West Bank of the Nile at Luxor. The Spanish archaeological mission, led by Dr. Antonio Morales, found 56 amphorae and close to 300 linen packets of natron and other materials used in the embalming process in a well a few feet northeast of the entrance to the tomb of Ipi.

The Middle Kingdom Theban Project studies two tombs in the Deir el-Bahari necropolis, the tomb of Henenu and the tomb of Ipi, to investigate the development of the Egyptian state as reflected in the religious, artistic, epigraphic and archaeological features of the tombs of important officials during the transformative period at the dawn of the Middle Kingdom. Many of the aspects of later Pharaonic periods first evolved during this period in the wake of Egypt’s unification after centuries of conflict. The evolution of mummification procedures, so strongly associated with Pharaonic Egypt, is one of those aspects.

The Middle Kingdom Theban Project studies two tombs in the Deir el-Bahari necropolis, the tomb of Henenu and the tomb of Ipi, to investigate the development of the Egyptian state as reflected in the religious, artistic, epigraphic and archaeological features of the tombs of important officials during the transformative period at the dawn of the Middle Kingdom. Many of the aspects of later Pharaonic periods first evolved during this period in the wake of Egypt’s unification after centuries of conflict. The evolution of mummification procedures, so strongly associated with Pharaonic Egypt, is one of those aspects.

The tomb of Ipi is on the northern hill of the necropolis in front of the now-destroyed temple of Dynasty XI pharaoh Mentuhotep II, a privileged location where the most important officials of the early Middle Kingdom were buried. Ipi was a vizier, a high advisor to Pharaoh Amenemhat I of the early 12th Dynasty, and the overseer of ancient Thebes. The tomb was first explored in 1921-1922 by American Egyptologist Herbert Winlock of the Metropolitan Museum of New York. He found the mummification materials during that excavation, but had no real understanding of their importance. Interested in them for their aesthetic value only, he removed four of the amphorae and left everything else in the room without cleaning or documenting them. Winlock never got back to them, and people forgot they were there until now.

The tomb of Ipi is on the northern hill of the necropolis in front of the now-destroyed temple of Dynasty XI pharaoh Mentuhotep II, a privileged location where the most important officials of the early Middle Kingdom were buried. Ipi was a vizier, a high advisor to Pharaoh Amenemhat I of the early 12th Dynasty, and the overseer of ancient Thebes. The tomb was first explored in 1921-1922 by American Egyptologist Herbert Winlock of the Metropolitan Museum of New York. He found the mummification materials during that excavation, but had no real understanding of their importance. Interested in them for their aesthetic value only, he removed four of the amphorae and left everything else in the room without cleaning or documenting them. Winlock never got back to them, and people forgot they were there until now.

Dr. Mahmoud Afifi, head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Department, points out that the discovery of such extensive materials directly connected to the mummification of a high official adds significantly to our understanding of the kind of embalming techniques, tools, textiles, chemicals and unguents used in the early Middle Kingdom which is when the mummification procedures that would reach their peak in the New Kingdom began to take form.

Dr. Mahmoud Afifi, head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Department, points out that the discovery of such extensive materials directly connected to the mummification of a high official adds significantly to our understanding of the kind of embalming techniques, tools, textiles, chemicals and unguents used in the early Middle Kingdom which is when the mummification procedures that would reach their peak in the New Kingdom began to take form.

Dr. Antonio Morales the Head of Spanish Mission said that the deposit of the mummification materials used for Ipi include inscriptions, various shrouds and linen sheets (4 m. long) shawls, and rolls of wide bandages, in addition to further types of cloths, rags, and pieces of slender wrappings destined to cover fingers, toes, and other parts of the vizier’s corpse.

Dr. Morales explained that jars contained around 300 sacks with natron salt, oils, sand, and other substances, as well as the stoppers of the jars and a scraper are also found. [A]mong the most outstanding pieces of the collection are the Nile clay and marl large jars, some with potmarks and hieratic.

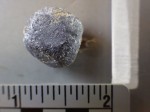

Because these items were used in the embalming process and were therefore impure, they couldn’t be included in the burial chamber with the sarcophagus. Biological remains including blood stains and clots were found on the bandages, and one of the linen packets contained Ipi’s heart. While the brain and heart were removed for optimal preservation by the time the embalming art reached its zenith in the New Kingdom, they were usually left in the body in the early Middle Kingdom. The fact that Ipi’s heart was removed and left in the materials dump rather than in a canopic jar as his stomach, intestines, lungs and liver were is likely an indication that his embalmers cut some corners.

Because these items were used in the embalming process and were therefore impure, they couldn’t be included in the burial chamber with the sarcophagus. Biological remains including blood stains and clots were found on the bandages, and one of the linen packets contained Ipi’s heart. While the brain and heart were removed for optimal preservation by the time the embalming art reached its zenith in the New Kingdom, they were usually left in the body in the early Middle Kingdom. The fact that Ipi’s heart was removed and left in the materials dump rather than in a canopic jar as his stomach, intestines, lungs and liver were is likely an indication that his embalmers cut some corners.

The materials are so extensive that the Middle Kingdom Theban Project team will have to work on them for at least one more campaign season. The linen strips will be analyzed by gas chromatography, mass spectrometry and other technologies that will identify trace substances like natron and other chemical and biological remains. From a scientific perspective, it’s a great thing that Winlock ignored this find. That left organic materials untouched and in their original environment so they could be preserved until there was such a thing as a gas chromatograph.

Here’s some excellent film of the discovery of the room and its wealth of mummification materials.