At least 400 Viking and Iron Age artifacts were stolen from the University Museum in Bergen, Norway, during the weekend of August 11-1. The burglars climbed scaffolding on the exterior of the museum’s building (currently undergoing renovation) and broke in through a 7th floor window. They ransacked the rooms where the objects were being kept in cabinets and on shelves, making off with hundreds of pieces.

At least 400 Viking and Iron Age artifacts were stolen from the University Museum in Bergen, Norway, during the weekend of August 11-1. The burglars climbed scaffolding on the exterior of the museum’s building (currently undergoing renovation) and broke in through a 7th floor window. They ransacked the rooms where the objects were being kept in cabinets and on shelves, making off with hundreds of pieces.

Two alarms rang on the evening of Saturday, August 12th. Security guards investigated the building, but reported nothing untoward, which does not speak highly of their competence given the 7th floor was left in a total shambles by the burglars. The theft was discovered on Monday by museum staff.

Two alarms rang on the evening of Saturday, August 12th. Security guards investigated the building, but reported nothing untoward, which does not speak highly of their competence given the 7th floor was left in a total shambles by the burglars. The theft was discovered on Monday by museum staff.

The museum acknowledges that the artifacts were insufficiently secured. In a painful irony, they were scheduled to be moved to a more secure location on August 14th, that same Monday when the theft was discovered.

The museum acknowledges that the artifacts were insufficiently secured. In a painful irony, they were scheduled to be moved to a more secure location on August 14th, that same Monday when the theft was discovered.

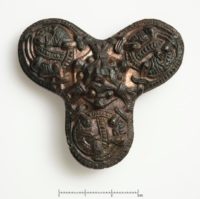

Conservators are still tallying up the stolen artifacts. Most of the more than 400 that have been identified so far date to the Iron Age (500 B.C.-1030 A.D.) and the Viking period (800-1030 A.D.). They are small, portable objects, primarily jewelry of negligible monetary value, nor is there any particular value in the metals they’re composed of. It’s their historical value that matters, and the thieves are unlikely to be able to cash in on that.

To the museum, however, the loss is devastating.

“For us as a museum it is to take care of the cultural heritage our most important task. We have not met our requirements. It is incomprehensible and no explanations are good enough. The items that are gone do not have so much economic value, but very high historical value. We can now only hope that the lost is coming back and we can work purposefully to prevent the like from happening again. But I feel heavy,” says the museum director [Henrik von Achen].

All safety systems have been reviewed, the scaffolding and building secured, but closing the barn door after the horses have fled is little consolation to the museum staff. Many of the objects were going to be on display in an upcoming Viking exhibition scheduled for later this year. Unless the artifacts are recovered quickly, the exhibition will probably have to be postponed, perhaps indefinitely.

All safety systems have been reviewed, the scaffolding and building secured, but closing the barn door after the horses have fled is little consolation to the museum staff. Many of the objects were going to be on display in an upcoming Viking exhibition scheduled for later this year. Unless the artifacts are recovered quickly, the exhibition will probably have to be postponed, perhaps indefinitely.

Norwegian police are actively investigating the theft, working with their counterparts in other countries in the hope of catching the thieves in the attempt to smuggle or sell the artifacts. The University Museum staff aren’t sitting on their hands waiting for the police to solve the crime. They are enlisting the power of social media to get the word out. As conservators work to inventory the stolen objects, images of the artifacts are being uploaded to a dedicated Facebook page. The museum asks that the photo album be shared as widely as possible and that people keep their eyes peeled for any pieces that might crop up on auction and sale sites that don’t monitor whether sellers have legitimate title to the items being sold. The more widely seen the artifacts are, the harder it will be for the thieves to unload them under the radar.

Norwegian police are actively investigating the theft, working with their counterparts in other countries in the hope of catching the thieves in the attempt to smuggle or sell the artifacts. The University Museum staff aren’t sitting on their hands waiting for the police to solve the crime. They are enlisting the power of social media to get the word out. As conservators work to inventory the stolen objects, images of the artifacts are being uploaded to a dedicated Facebook page. The museum asks that the photo album be shared as widely as possible and that people keep their eyes peeled for any pieces that might crop up on auction and sale sites that don’t monitor whether sellers have legitimate title to the items being sold. The more widely seen the artifacts are, the harder it will be for the thieves to unload them under the radar.