The only known surviving portrait taken from life of sibling literary luminaries Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë has gone home. Part of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London, the painting is on display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth for the first time since 1984 to take part in an exhibition honoring the bicentenary of Emily’s birthday (July 30th, 1818). Emily, author of Wuthering Heights, was the fifth of six children, born between brother Patrick Branwell and youngest sister Anne. This is the only undisputed portrait of Emily (experts disagree about whether another painting by Branwell is of Emily or Anne).

The only known surviving portrait taken from life of sibling literary luminaries Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë has gone home. Part of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London, the painting is on display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth for the first time since 1984 to take part in an exhibition honoring the bicentenary of Emily’s birthday (July 30th, 1818). Emily, author of Wuthering Heights, was the fifth of six children, born between brother Patrick Branwell and youngest sister Anne. This is the only undisputed portrait of Emily (experts disagree about whether another painting by Branwell is of Emily or Anne).

It was painted by Branwell Brontë around 1834 at the Haworth parsonage, the family’s home on the Yorkshire moors for many isolated years of their childhood. That parsonage is now the Brontë Parsonage Museum. It usually has to make do with a copy of the famous group portrait, but the original work is now being exhibited in the place where it was painted in Emily’s honor. The honor is a transitory one, however. The painting will only be on view at the parsonage through August 31st.

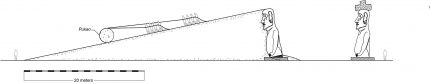

The work has quite the checkered history. Branwell originally included a self-portrait in the group between Emily and Charlotte, but for unknown reasons he painted himself out, covering his likeness with a weirdly random green ectoplasmic pillar. Because of that odd feature, the painting is known as the Pillar Portrait.

Patrick died in September 1848, followed less than two months later by Emily. Anne died five months after her sister in May of 1849. Charlotte was the last survivor of the Brontë siblings.

Her friend and biographer, novelist Elizabeth Gaskell (author of Cranford and North and South, among others) saw the portrait when she visited Charlotte at Haworth in 1853. She described it in less than glowing terms in her bestselling biography of the author, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, published in 1857:

Her friend and biographer, novelist Elizabeth Gaskell (author of Cranford and North and South, among others) saw the portrait when she visited Charlotte at Haworth in 1853. She described it in less than glowing terms in her bestselling biography of the author, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, published in 1857:

I have seen an oil painting of [Branwell’s], done I know not when, but probably about this time [1835]. It was a group of his sisters, life-size, three-quarters’ length; not much better than sign-painting, as to manipulation; but the likenesses were, I should think, admirable. I could only judge of the fidelity with which the other two were depicted, from the striking resemblance which Charlotte, upholding the great frame of canvas, and consequently standing right behind it, bore to her own representation, though it must have been ten years and more since the portraits were taken. The picture was divided, almost in the middle, by a great pillar. On the side of the column which was lighted by the sun, stood Charlotte, in the womanly dress of that day of gigot sleeves and large collars. On the deeply shadowed side, was Emily, with Anne’s gentle face resting on her shoulder. Emily’s countenance struck me as full of power; Charlotte’s of solicitude; Anne’s of tenderness. The two younger seemed hardly to have attained their full growth, though Emily was taller than Charlotte; they had cropped hair, and a more girlish dress. I remember looking on those two sad, earnest, shadowed faces, and wondering whether I could trace the mysterious expression which is said to foretell an early death. I had some fond superstitious hope that the column divided their fates from hers, who stood apart in the canvas, as in life she survived. I liked to see that the bright side of the pillar was towards her — that the light in the picture fell on her: I might more truly have sought in her presentment — nay, in her living face — for the sign of death — in her prime. They were good likenesses, however badly executed.

Charlotte lived at Haworth until her tragically premature death in 1855. She had married her father’s curate Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1854 and became pregnant shortly thereafter. She and her unborn child died nine months after the wedding. Charlotte was just shy of her 39th birthday.

Nicholls stayed on as Patrick Brontë’s curate until the latter’s death in 1861, then he moved back to his hometown of Banagher, Ireland. He sold the contents of Haworth but kept manuscripts, ephemera and personal effects, including the group painting even though he apparently hated it. He put it on top of an upstairs cupboard and let people believe it was lost for decades.

It was rediscovered in 1913, seven years after Nicholls’ death, by his second wife and cousin, Mary. By then it was out of its frame, off its stretcher and folded in four. The widow told her niece that Nicholls “disliked them very much. He thought they were very ugly representations of the girls, and I think meant to destroy them, but perhaps shrank from doing so — you see, there is only one other existing portrait of Charlotte, and none at all of Emily and Anne.”

It was rediscovered in 1913, seven years after Nicholls’ death, by his second wife and cousin, Mary. By then it was out of its frame, off its stretcher and folded in four. The widow told her niece that Nicholls “disliked them very much. He thought they were very ugly representations of the girls, and I think meant to destroy them, but perhaps shrank from doing so — you see, there is only one other existing portrait of Charlotte, and none at all of Emily and Anne.”

That last bit isn’t true. There was actually a portrait by Branwell of Emily or Anne, (scholars disagree) found on top of the same cupboard as the Pillar Portrait. It was cut out of a group portrait, the rest of which has been lost.

Mary Nicholls sold the group portrait in 1914 to the National Portrait Gallery. Most of the rest of the manuscripts and Brontë memorabilia she sold after her husband’s death or that was sold after her death in 1916 are now part of the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection.