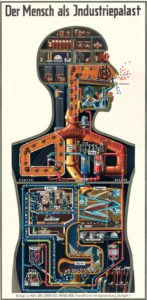

It has been almost a decade since I first saved a draft post about Dr. Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), the gynecologist and popular science writer who in 1926 designed an image you’ve almost certainly seen before: “Man as Industrial Palace,” an infographic depicting the functions of the human body as an industrial complex. It has taken me this long to delve as deeply as I felt this image deserved because detailed information about Kahn is hard to find on the Internet and because I wanted to include copious English-language labels for the amazing illustration. The originals are in German, and even then very little of what you see is labeled in the intricate poster. The visual takes precedence over the verbal. An exceptional trilingual monograph of Fritz Kahn’s life and works by Uta von Debschitz and Thilo von Debschitz came to my rescue on every count. I owe this post to them.

It has been almost a decade since I first saved a draft post about Dr. Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), the gynecologist and popular science writer who in 1926 designed an image you’ve almost certainly seen before: “Man as Industrial Palace,” an infographic depicting the functions of the human body as an industrial complex. It has taken me this long to delve as deeply as I felt this image deserved because detailed information about Kahn is hard to find on the Internet and because I wanted to include copious English-language labels for the amazing illustration. The originals are in German, and even then very little of what you see is labeled in the intricate poster. The visual takes precedence over the verbal. An exceptional trilingual monograph of Fritz Kahn’s life and works by Uta von Debschitz and Thilo von Debschitz came to my rescue on every count. I owe this post to them.

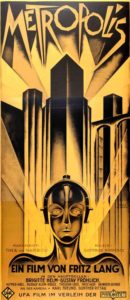

The analogy of man to machine was a widespread cultural trend in the 1920s and 30s. The explosion of industry and consumer technology in the early 20th century inspired new approaches to art and literature, integrating the human experience into the dynamic speed, power and sharp edges of the machine age. Futurists stuffed steel ball bearings into roast chicken,  Fritz Lang made men cogs in one machine and made a woman out of another, and Fritz Kahn diagrammed the complexities of human biology by comparing them to industrial and household machines.

Fritz Lang made men cogs in one machine and made a woman out of another, and Fritz Kahn diagrammed the complexities of human biology by comparing them to industrial and household machines.

Born in 1888 in Halle der Saale, Fritz was the son of Arthur and Hedwig Kahn. Arthur was a physician and a writer and his son would follow in his father’s footsteps. He started writing popular science articles for the journal Kosmos while still an undergraduate at Berlin University in 1907. By the time he graduated from medical school as a gynecologist in 1914, he’d already written a book about astronomy for the general public, and after serving as a medic in World War I, he continued to work both as a doctor and as an author, publishing a successful book about the cell in 1919 and writing articles on, among other things, archaeology, aviation, Jewish history and his war experience.

His books sold briskly, going into repeated print runs in their first years, but it was his knack for illustration and design that would become his trademark. (Quite literally, in fact, as in later years a team of illustrators would bring his design concepts to fruition and those images would be stamped with his FK trademark.) From 1922 through 1931, the heyday of the Weimar Republic, Kahn published a five-volume study of human biology, Das Leben des Menschen (“The Life of Man”), to international best-selling acclaim, wrote articles for Kosmos and other magazines, gave lectures, edited the Encyclopaedia Judaica all the while continuing to practice medicine.

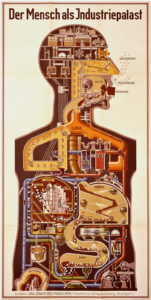

It was in Das Leben des Menschen that Fritz Kahn published the image that would become most indelibly associated with him. The supplementary folding plate entitled Man as Industrial Palace depicted the primary functions of the body as a complex factory complete with homunculi busily operating the controls. Men in suits in the conference rooms of the brain make decisions as Reason and Will; the Mind is run by a librarian. A man in a headset operates a telegraph for Hearing. A photographer snaps the shutter of the bellows camera for Sight. Men at lightboards monitor valves and signals of the Muscle, Gland and Nerve Control Centers. Workers shift gears to move food through the digestive tract. A man seated at a stamping machine produces red corpuscles in the Blood Marrow. Winches, pulleys, pistons, cables and tubes form the infrastructure of all of the body’s systems.

It was in Das Leben des Menschen that Fritz Kahn published the image that would become most indelibly associated with him. The supplementary folding plate entitled Man as Industrial Palace depicted the primary functions of the body as a complex factory complete with homunculi busily operating the controls. Men in suits in the conference rooms of the brain make decisions as Reason and Will; the Mind is run by a librarian. A man in a headset operates a telegraph for Hearing. A photographer snaps the shutter of the bellows camera for Sight. Men at lightboards monitor valves and signals of the Muscle, Gland and Nerve Control Centers. Workers shift gears to move food through the digestive tract. A man seated at a stamping machine produces red corpuscles in the Blood Marrow. Winches, pulleys, pistons, cables and tubes form the infrastructure of all of the body’s systems.

Here is an illustration that labels the “Man as Industrial Palace” graphic in detail. It was included in an explanatory supplement to the poster printed in 1926. I’ve put the lettered and numbered labels translated into English in this pdf file.

That was the last of Fritz Kahn’s books initially published in Europe. Kahn, whose grandfather had been a cantor, whose father was deeply devout in his Judaism, who had published tracts against anti-Semitism in the 1920s and was a committed Zionist, happened to be in Palestine when Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. He wisely decided to stay where he was, and he and his family settled in Jerusalem. In Germany his books were banned and burned, but that didn’t stop his publisher from reprinting a version of Das Leben des Menschen, illustrations included, without attribution and with the addition of a vile new chapter by Nazi sympathizer Gerhard Venzmer promoting scientific racism and anti-Semitism.

He left Palestine in 1939 and moved to France where he barely managed to stay ahead of the German invaders. In 1940 he was interned in Vichy France, but thanks to the Herculean efforts of his wife and humanitarian Varian Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee, he was released and the couple fled to Spain and Portugal. They were able to emigrate to the United States in 1941 thanks to the intervention of Albert Einstein. “As I have a high opinion of Dr. Kahn as personality and as author I should be thankful if the visa would be granted to him,” Einstein wrote to the US Consul in Lisbon.

Kahn’s books were already known in the US, but it took him a while to get a foothold in the American literary market. When Das Leben des Menschen was translated into English and published in the United States as Man in Structure and Function in 1943, he finally had a hit again. He continued to publish popular science books even as his generalist approach began to fall out of fashion in favor of specialist authors, and he eventually returned to Europe. He died in Switzerland in 1968.

Some of his books remained in print into the 1980s, but the appetite for his approach had waned and his striking imagery faded from the wider cultural consciousness. Nonetheless, his man-machine visions had a profound influence on many, from his contemporaries like patent medicine hawker Dr. Ferdinand-Gabriel-Aimé Brunerye, to modern-day artists like Madrid illustrator Fernando Vicente who channels a Frankenstein creature of Vargas, Vesalius and Kahn to create dissected biomechanical pin-up girls.

In the Internet era, his images, particularly Man as Industrial Palace, took on new life. His prescient grasp of what would become the ubiquitous infographic — a picture conveying simplified data — made Kahn’s work on trend once again. Photos of them are widely shared and reproductions of the poster are easily available online. The originals will run you a cool two grand on eBay. The larger format promotional posters subscribers to Das Leben des Menschen received sell for much more than that ($3,750 at a 2007 Christie’s auction, for example). Institutions have given Kahn long overdue attention in the past decade as well, and exhibitions including his work have been displayed at the Berlin Medical Historical Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Art Basel and other museums around the world.

Some of those exhibitions have included an interactive animated display of Man as Industrial Palace created by graphic artist Henning M. Lederer, and the animation is so awesome that it inspired this entire post. If any graphic in the world was ideally designed to see in movement, Fritz Kahn’s man-machine is that graphic.

From the moment on that Henning Lederer got to know Kahn’s poster “Man as Industrial Palace” in 2006, he had the idea to animate this complex and strange way of explaining the functions of a body. He wanted to continue Fritz Kahn’s act of replacing a biological with a technological structure by transferring this depiction with the help of motion graphics and animation. In addition to the moving images, as a framework, Henning created a cabinet for his work including a mixture of old and new technology. This new version of the “Industrial Palace“ is an interactive installation for the audience to interact with – and by this to explore the different cycles of this human machinery.

If you missed this installation in the many museums where it has been exhibited alongside Kahn’s originals, you won’t get to explore the full genius of Lederer’s animation which divides the diagram into six cycles (Respiration, Blood Circulation, Digestive Circuit, Control Center and Industrial Palace) and allows visitors to push a button to see each in action. Thankfully, Lederer uploaded the Industrial Palace animation to Vimeo for the benefit of biomech/history/anatomy/industrial arts nerds everywhere.