Theriac was a complex medical preparation made from dozens of ingredients that was first devised as an antidote to all poisons and venoms: the fabled Mithridatium allegedly developed by Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, in the 3rd century B.C. The recipe was significantly expanded in the 2nd century by Nero’s physician Andromachus. To distinguish the updated formula from its ancient antecedent, the old one was renamed after its inventor and the new one became Theriac.

Once the recipes were split, Theriac’s prescribed uses multiplied and it became an all-purpose panacea. People used it to prevent and treat infectious disease, primarily Bubonic Plague, and it was a popular remedy well into the 19th century. It was made in large quantities during epidemics and was deemed so import that cities granted pharmacists official Theriac-making rights. Official production had to be transparent to the public to the point of printing and distribution of the recipe used in a production event.

Its wide range of ingredients include known narcotics like poppy and known poisons like sea squill, a leafy plant that makes an excellent rat poison that was first recorded as a medicinal plant in a 16th century B.C. Egyptian papyrus, one of the earliest surviving medical treatises. Since modern medicine and understanding of disease eclipsed the humors theory and sounded the death knell for Theriac’s regular use, Theriac has never before been pharmacologically analyzed to study its effects, if any.

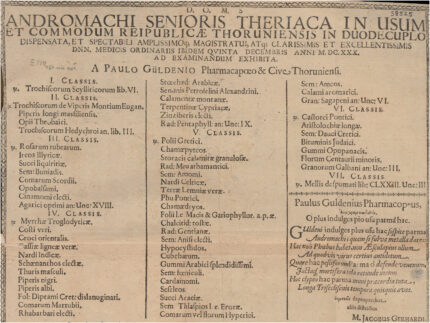

Researchers in Poland determined to recreate and analyze Theriac to see if any of the properties of its individual ingredients appear in the finished product. The research teams used one of only two known surviving copies of a Theriac recipe elaborated by Paul Guldenius, an apothecary in Toruń, central Poland, who was granted permission to produce the official Theriac of the city. Guldenius published his 61-ingredient recipe on a one-sided printed flyer in 1630.

The main difficulty during our work was the correct translation of the names of the plants used by the apothecary, which had to be identified with particular care and matched with contemporary botanical nomenclature.

Theriac was prepared in a complex process involving many raw materials that were difficult to access. Their cost was very high, making the medicine one of the most expensive of its time. Although it was used in very small doses, the price of a single dose weighing about 4 grams was equal to the value of a chicken or a half goose. The preparation contained some ingredients that could have certain pharmacological effects, and some are considered poisonous today. Nevertheless, their amount in a single serving of the medicine was very small, e.g. in the case of the rather poisonous sea onion it was 50 times less than the dose considered safe today. As a result, our research indicates that Theriac used according to the recommendations of the time could not have been poisonous.

Did it therefore have therapeutic properties? A full answer to this question still requires precise analyses of the reconstructed preparation. Still, preliminary findings indicate that the possible effectiveness of Theriac was based mainly on the placebo effect. Although there is no lack of substances showing therapeutic effects in this medicine with the recommended dosage, their amounts are far from sufficient to have a real impact on human health.

The study has been published in the journal Journal of Ethnopharmacology and can be read in its entirety here.