Harry Patch was a machine-gunner in the Duke of Cornwalls’s Light Infantry, conscripted into military service when he was 18 years old. He died yesterday in his sleep.

Harry Patch was a machine-gunner in the Duke of Cornwalls’s Light Infantry, conscripted into military service when he was 18 years old. He died yesterday in his sleep.

He was known as “the last Tommy” because he was last British veteran of the trenches of World War I.

“Tommy” was the nickname for the common British infantryman, immortalized in Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Tommy”.

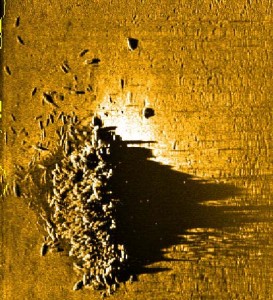

Harry Patch fought at Passchendaele, the third battle at Ypres, Belgium, in 1917. 70,000 British troops died in that battle. He never spoke of his wartime experiences until he was 100 years old, believe it or not, when he was interviewed for a documentary.

He grew up in Coombe Down, near Bath, left school at 15 and trained as a plumber. He was 16 when war broke out and reached 18 just as conscription was being introduced. He joined the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry.

“I knew what it was going to be like: dirty, filthy, insanitary,” he said in an interview with The Daily Telegraph.

He was removed from the front line on September 22 1917, after being injured in an artillery bombardment which killed his friends.

Mr Patch recalled: “I can remember the shell bursting. I saw the flash, I must have passed out. The next thing I could remember was the dressing station. A wound in my groin. The nurse painted something around it to stop the lice getting at it. I was given a good hot bath. The lice came off – you could pick them up with a shovel – bloody things.”

Mr. Patch didn’t truck much with the glorious war narrative, needless to say. RIP, brother.

This leaves only one remaining British veteran of WWI. Claude Choules is a Royal Navy vet now living in Australia. During World War I, he served on the battleship HMS Revenge and was witness both to the surrender of the German Imperial Navy in 1918 and to its scuttling by its German commander, Admiral Ludwig von Reutera, a few months later.