Italian police announced today that they’ve broken up a huge looting ring, recovering thousands of artifacts destined to be smuggled to countries including the United States.

Italian police announced today that they’ve broken up a huge looting ring, recovering thousands of artifacts destined to be smuggled to countries including the United States.

During more than a year of investigations, authorities recovered nearly 1,700 statues, vases and other artifacts dating from pre-Roman times to the heyday of the empire. Police flagged 19 people for possible investigation by prosecutors.

The artifacts were mainly dug out from tombs near Naples and Venice and included a bronze bust of the emperor Augustus, customs police in Rome said.

Some pieces were already in the United States. Italian authorities worked with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Connecticut to repatriate 47 6th and 5th centuries B.C. statues that had been looted from a tomb in southern Italy.

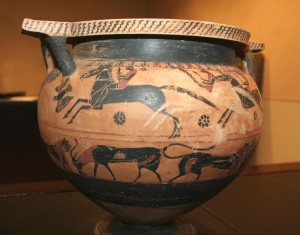

This is the second time in two weeks that the ICE has returned artifacts from that period looted from southern Italy. Just last week they returned a Corinthian column krater from 580 to 570 B.C. that had been trafficked by Giacomo Medici (the now-convicted felon who directed the looting and sale of the Euprhonios krater) and wall panel fresco from Pompeii that had been stolen in 1997.

This is the second time in two weeks that the ICE has returned artifacts from that period looted from southern Italy. Just last week they returned a Corinthian column krater from 580 to 570 B.C. that had been trafficked by Giacomo Medici (the now-convicted felon who directed the looting and sale of the Euprhonios krater) and wall panel fresco from Pompeii that had been stolen in 1997.

The Corinthian krater, incidentally, was recovered from Christie’s in June. It has first gone on the market at a Sotheby’s auction in 1985. Dirty, dirty, dirty.