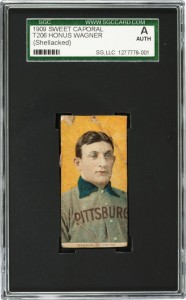

The School Sisters of Notre Dame are $220,000 richer today, thanks to baseball legend Honus Wagner. Earlier this year, the brother of a nun belonging to that order died, leaving the sisters all his worldly possessions, including a safe deposit box containing among other baseball cards, the Holy Grail, if you’ll pardon the term, of collectors: a T206 Honus Wagner card.

The School Sisters of Notre Dame are $220,000 richer today, thanks to baseball legend Honus Wagner. Earlier this year, the brother of a nun belonging to that order died, leaving the sisters all his worldly possessions, including a safe deposit box containing among other baseball cards, the Holy Grail, if you’ll pardon the term, of collectors: a T206 Honus Wagner card.

There are only between 50 and 60 T206 Honus Wagner cards known in existence. This one was an unknown in the marketplace because the bequeather had had it since 1936. He knew it was a big ticket item. He left a note in the safe deposit box that said “Although damaged, this card will be exponentially valuable in the 21st Century.”

Produced by the American Tobacco Company, the T206 series ran between 1909 and 1911. The set is called “The Monster” by collectors, because it’s so hard to complete. He refused to allow ATC the use of his image, possibly because they wouldn’t pay him enough, possibly because he didn’t want to be used to market tobacco to the kids who revered him. The latter is the most popular story, but nobody really knows why he shut them down. As a result, only 50 to 200 of the limited original print run of Honus Wagner T206 cards were ever distributed to the public. By 1933 it was already the most valuable baseball card in the world, valued at $50.

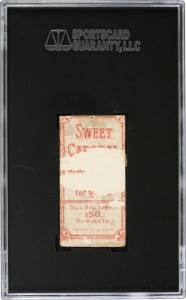

The result of his intransigence is that the T206 Honus Wagner is the single most desirable baseball card. One in near-mint condition sold in 2007 for $2.8 million, the most expensive baseball card ever sold. The School Sisters of Notre Dame’s card, however, is in not so great condition. There are multiple creases, 3 of the white borders have been cut off, the back is damaged from it being stuck in a scrapbook, there’s a tack mark over Honus’ head and it was shellacked decades ago.

The result of his intransigence is that the T206 Honus Wagner is the single most desirable baseball card. One in near-mint condition sold in 2007 for $2.8 million, the most expensive baseball card ever sold. The School Sisters of Notre Dame’s card, however, is in not so great condition. There are multiple creases, 3 of the white borders have been cut off, the back is damaged from it being stuck in a scrapbook, there’s a tack mark over Honus’ head and it was shellacked decades ago.

That notwithstanding, the card sold for $262,900, $162,900 over its pre-sale estimate and a good $60,000 above its retail worth. (The $42,900 not going to the sisters is the 19.5% buyer’s premium.) The buyer, Doug Walton, is well aware of this since he himself deals in sports cards and memorabilia. It was no deterrent, especially with the great brother-nun-1936 back story.

“I have been in the market for this card for a long time,” Walton told CNN. “It is the Mona Lisa of baseball cards.” […]

Walton, managing partner of Walton Sports Cards and Collectibles, said he’s tried three previous times to buy a Wagner card, but was outbid. He plans to have the card make the rounds of the company’s stores in Tennessee, Florida and South Carolina.

Honus Wagner was one of the first 5 baseball players in the Hall of Fame. He played for 21 seasons, 18 of them with the Pittsburgh Pirates, going to the World Series with them twice. They won in 1909 against Ty Cobb’s Detroit Tigers. He was an outstanding all-around player with a .328 career batting average and is widely considered the greatest shortstop of all time.

Adorable story interlude: When news of the bequest started to make the press, Sister Virginia Muller, a former treasurer of the order who was assigned as representative of the donor’s estate, received a phone call from Leslie Roberts, Honus Wagner’s granddaughter. She was happy the card would be helping support the order’s educational mission in the US and abroad, and she shared some memories of her grandfather. She said he would sit her on his lap and feed her Hershey’s chocolates while telling her tall tales. Once, he told her, he hit the longest home run of all time when he hit a ball out of the park onto a train heading to California. ![]()