In February of 1842, Charlotte and Emily Brontë moved to Brussels to enroll in a pensionnat (boarding school) for young ladies run by Belgian teacher Claire Zoé Parent Héger with the help of her husband Constantin who also taught at the nearby Athénée Royale school. The sisters’ ultimate goal was to open a school of their own back home in Haworth, Yorkshire, and quality foreign language instruction, particularly of French, would be key to their school’s success. The Brontës couldn’t afford board and tuition at the pensionnat, so Charlotte, then 25 years old, taught English and Emily, then 23, taught music at the school to pay their way.

In February of 1842, Charlotte and Emily Brontë moved to Brussels to enroll in a pensionnat (boarding school) for young ladies run by Belgian teacher Claire Zoé Parent Héger with the help of her husband Constantin who also taught at the nearby Athénée Royale school. The sisters’ ultimate goal was to open a school of their own back home in Haworth, Yorkshire, and quality foreign language instruction, particularly of French, would be key to their school’s success. The Brontës couldn’t afford board and tuition at the pensionnat, so Charlotte, then 25 years old, taught English and Emily, then 23, taught music at the school to pay their way.

Constantin Héger was their French teacher. Charlotte described him thus when she first arrived:

Constantin Héger was their French teacher. Charlotte described him thus when she first arrived:

He is professor of rhetoric, a man of power as to mind, but very choleric and irritable in temperament; a little black being, with a face that varies in expression. Sometimes he borrows the lineaments of an insane tom-cat, sometimes those of a delirious hyena; occasionally, but very seldom, he discards these perilous attractions and assumes an air nor above 100 degrees removed from mild and gentlemanlike….

They already spoke and wrote basic French, so Constantin gave the sisters writing assignments based on French literature. He encouraged them to choose their own subjects inspired by the French authors they had read in class. On March 16, 1842, Charlotte handed in the first of these assignments: a short story called L’Ingratitude, inspired in part by Jean de la Fontaine’s fable The Rat Retired From The World. It tells the story of a spoiled young rat who leaves his father’s humble but loving home for greener pastures only to find they’re not so green after all.

They already spoke and wrote basic French, so Constantin gave the sisters writing assignments based on French literature. He encouraged them to choose their own subjects inspired by the French authors they had read in class. On March 16, 1842, Charlotte handed in the first of these assignments: a short story called L’Ingratitude, inspired in part by Jean de la Fontaine’s fable The Rat Retired From The World. It tells the story of a spoiled young rat who leaves his father’s humble but loving home for greener pastures only to find they’re not so green after all.

In November of 1842, Charlotte and Emily returned to Haworth when their aunt Elizabeth Branwell passed away. Charlotte returned alone to the pensionnat in January of 1843 to teach English, and, as she admitted a few years later in a letter to a friend, to be near Constantin Héger with whom she had fallen in love. Her feelings were unrequited. Constantin was devoutly religious, a happily married man with children; his wife ran the school. This was not a comfortable situation.

In November of 1842, Charlotte and Emily returned to Haworth when their aunt Elizabeth Branwell passed away. Charlotte returned alone to the pensionnat in January of 1843 to teach English, and, as she admitted a few years later in a letter to a friend, to be near Constantin Héger with whom she had fallen in love. Her feelings were unrequited. Constantin was devoutly religious, a happily married man with children; his wife ran the school. This was not a comfortable situation.

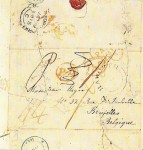

A year later, Charlotte returned to Haworth. She wrote to Constantin for the next two years, a series of reserved and somber love letters in French, four of which have survived. Two of them were reputedly torn up and taped back together; some say Madame Héger tore them in disgust, some that Constantin tore them up and his wife rescued them from the bin for unknown reasons. Charlotte hadn’t been published back then (Jane Eyre was published in 1847), so it’s not likely that Madame saw them as having literary value.

A year later, Charlotte returned to Haworth. She wrote to Constantin for the next two years, a series of reserved and somber love letters in French, four of which have survived. Two of them were reputedly torn up and taped back together; some say Madame Héger tore them in disgust, some that Constantin tore them up and his wife rescued them from the bin for unknown reasons. Charlotte hadn’t been published back then (Jane Eyre was published in 1847), so it’s not likely that Madame saw them as having literary value.

Here’s a passage from one of those letters. The contrast with her initial impression of him is notable.

Day or night I find neither rest nor peace – if I sleep I have tormenting dreams in which I see you always severe, always saturnine and angry with me … I would not know what to do with a whole and complete friendship – I am not accustomed to it – but you showed a little interest in me when I was your pupil in Brussels – and I cling to the preservation of this little interest – I cling to it as I would cling on to life.

Her unrequited love for her teacher inspired Charlotte’s 1853 novel Villette. Spoiler alert! In the book, the fictional teacher character, M. Paul Emanuel, dies in the end.

In real life it was Charlotte who would die before her time. She passed away in 1855, a celebrated author just 38 years old. Her friend and fellow author Elizabeth Gaskell published a biography, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, in 1857. Gaskell interviewed Constantin Héger for the book but decided not to write about Charlotte’s inappropriate feelings for a married man.

It would take over half a century for the truth to out. In 1913, Constantin and Claire’s son Paul Héger donated Charlotte’s letters to the British Museum and allowed them to be published in the Times. Belgian coal magnate and art collector Raoul Warocqué read the letters in the paper and coveted them. He wrote to Paul asking if there were any more extant Brontë letters that he could buy. There were not, but Paul had another Brontë memento he was willing to part with: Charlotte’s handwritten manuscript of L’Ingratitude.

Warocqué’s collections are now in the Musée Royal de Mariemont. Brontë scholar Brian Bracken was looking through the Musée Royal’s catalog looking for information on Vital Héger, Constantin’s brother, when he found a reference to a manuscript by Charlotte Brontë. It was L’Ingratitude, forgotten since 1914.

On Wednesday the London Review of Books published L’Ingratitude for the first time. It’s posted in the original French and in an English translation, and there’s an audio version read by Gillian Anderson.